by Niall Chithelen

Night Bus—Beijing

The night bus takes you across the city in a straight shot. This city has straight shots, it’s wide across, you span some middle area, and who knows where the night bus goes when you leave.

The night bus shows up at odd times; you realized shamefully late that there even was a schedule. The other people who take the night bus aren’t like you, not taking it for your reasons, whatever those reasons are. They take their folded-up delivery bikes and sigh off at their stop. You stand up a few blocks out and then swing out, tilting home.

The night bus is where you collect yourself after a social evening, where the emptied streets remind you that you are anonymous and you return to the grey neighborhood where your footsteps are loud after midnight. Usually you are grateful for this strange nighttime routine. Sometimes you wish you stayed longer among the neon lights.

Seaside—San Diego

In the daylight, this route takes you up and down a hill along the water and you can breathe some ocean breaths. Bus or no bus, this is a sight better than most people get to see today. You’ve stepped in this ocean only once, though, dunked yourself into it, nervous, unsure what you had to lose; mostly you’ve seen it through windows or past stone walls.

On the way back, in the dark, you don’t notice the water. It’s not window time anymore, but instead looking down at your black plastic grocery bag time, or your phone, where you have pulled up a video that will stop playing if you change applications, so that you don’t check your messages so often. But you’re not good at not checking. You change applications. It’s a shame you’re heading home for no reason other than being done, out there.

As you step off at your inland corner, the ocean waits quietly, not too far away, wondering when you might return again.

Line 52—Tompkins County, New York

My winter boots are much too big, not in fit, just in general, so I’ve ruined some pretty nice shoes treading carefully during snow season. To or from work, I saw a bus I never took, bus 52, from Ithaca to Caroline. I suppose Caroline is a town, but maybe it isn’t—I was struck with the thought of the bus, plaintive, searching:

Line 52: Caroline

please come home

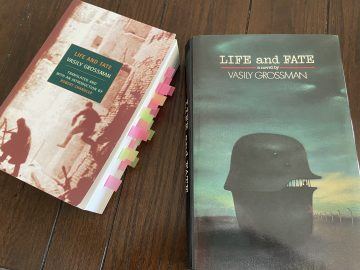

Most people associate the Cold War with several decades of intense political and economic competition between the United States and Soviet Union. A constant back and forth punctuated by dramatic moments such as the Berlin Airlift, the Berlin Wall, the arms race, the space race, the Bay of Pigs, the Cuban Missile Crisis, Nixon’s visit to China, the Olympic boycotts, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” and eventually the collapse of the Soviet system.

Most people associate the Cold War with several decades of intense political and economic competition between the United States and Soviet Union. A constant back and forth punctuated by dramatic moments such as the Berlin Airlift, the Berlin Wall, the arms race, the space race, the Bay of Pigs, the Cuban Missile Crisis, Nixon’s visit to China, the Olympic boycotts, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” and eventually the collapse of the Soviet system.

Where is philosophy in public life? Can we point to how the world in 2020 is different than it was in 2010 or 1990 because of philosophical research?

Where is philosophy in public life? Can we point to how the world in 2020 is different than it was in 2010 or 1990 because of philosophical research?

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in a typhoon of steel and firepower without precedent in history. In spite of telltale signs and repeated warnings, Joseph Stalin who had indulged in wishful thinking was caught completely off guard. He was so stunned that he became almost catatonic, shutting himself in his dacha, not even coming out to make a formal announcement. It was days later that he regained his composure and spoke to the nation from the heart, awakening a decrepit albeit enormous war machine that would change the fate of tens of millions forever. By this time, the German juggernaut had advanced almost to the doors of Moscow, and the Soviet Union threw everything that it had to stop Hitler from breaking down the door and bringing the whole rotten structure on the Russian people’s heads, as the Führer had boasted of doing.

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in a typhoon of steel and firepower without precedent in history. In spite of telltale signs and repeated warnings, Joseph Stalin who had indulged in wishful thinking was caught completely off guard. He was so stunned that he became almost catatonic, shutting himself in his dacha, not even coming out to make a formal announcement. It was days later that he regained his composure and spoke to the nation from the heart, awakening a decrepit albeit enormous war machine that would change the fate of tens of millions forever. By this time, the German juggernaut had advanced almost to the doors of Moscow, and the Soviet Union threw everything that it had to stop Hitler from breaking down the door and bringing the whole rotten structure on the Russian people’s heads, as the Führer had boasted of doing.

Ryan Ruby is a novelist, translator, critic, and poet who lives, as I do, in Berlin. Back in the summer of 2018, I attended an event at TOP, an art space in Neukölln, where along with journalist Ben Mauk and translator Anne Posten, his colleagues at the Berlin Writers’ Workshop, he was reading from work in progress. Ryan read from a project he called Context Collapse, which, if I remember correctly, he described as a “poem containing the history of poetry.” But to my ears, it sounded more like an academic paper than a poem, with jargon imported from disciplines such as media theory, economics, and literary criticism. It even contained statistics, citations from previous scholarship, and explanatory footnotes, written in blank verse, which were printed out, shuffled up, and distributed to the audience. Throughout the reading, Ryan would hold up a number on a sheet of paper corresponding to the footnote in the text, and a voice from the audience would read it aloud, creating a spatialized, polyvocal sonic environment as well as, to be perfectly honest, a feeling of information overload. Later, I asked him to send me the excerpt, so I could delve deeper into what he had written at a slower pace than readings typically afford—and I’ve been looking forward to seeing the finished project ever since. And now that it is, I am publishing the first suite of excerpts from Context Collapse at Statorec, where I am editor-in-chief.

Ryan Ruby is a novelist, translator, critic, and poet who lives, as I do, in Berlin. Back in the summer of 2018, I attended an event at TOP, an art space in Neukölln, where along with journalist Ben Mauk and translator Anne Posten, his colleagues at the Berlin Writers’ Workshop, he was reading from work in progress. Ryan read from a project he called Context Collapse, which, if I remember correctly, he described as a “poem containing the history of poetry.” But to my ears, it sounded more like an academic paper than a poem, with jargon imported from disciplines such as media theory, economics, and literary criticism. It even contained statistics, citations from previous scholarship, and explanatory footnotes, written in blank verse, which were printed out, shuffled up, and distributed to the audience. Throughout the reading, Ryan would hold up a number on a sheet of paper corresponding to the footnote in the text, and a voice from the audience would read it aloud, creating a spatialized, polyvocal sonic environment as well as, to be perfectly honest, a feeling of information overload. Later, I asked him to send me the excerpt, so I could delve deeper into what he had written at a slower pace than readings typically afford—and I’ve been looking forward to seeing the finished project ever since. And now that it is, I am publishing the first suite of excerpts from Context Collapse at Statorec, where I am editor-in-chief.

The case for men’s rights follows straightforwardly from the feminist critique of the structural injustice of gender rules and roles. Yes, these rules are wrong because they oppress women. But they are also wrong because they oppress men, whether by causing physical, emotional and moral suffering or callously neglecting them. Unfortunately the feminist movement has tended to neglect this, assuming that if women are the losers from a patriarchal social order, then men must be the winners.

The case for men’s rights follows straightforwardly from the feminist critique of the structural injustice of gender rules and roles. Yes, these rules are wrong because they oppress women. But they are also wrong because they oppress men, whether by causing physical, emotional and moral suffering or callously neglecting them. Unfortunately the feminist movement has tended to neglect this, assuming that if women are the losers from a patriarchal social order, then men must be the winners.