by Anitra Pavlico

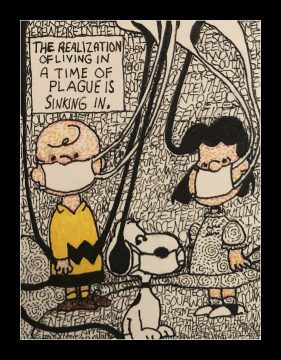

There has been much discussion lately of whether the COVID-19 pandemic will spell the end of globalization. It’s hard to get economists to agree on the meaning of the numbers, or foreign policy analysts to commit to a vision of the future in a world that changes from one moment to the next. Globalization means different things to different people and entities. Its many facets, and many narratives about those facets, complicate discussion about either a contraction or a resurgence of globalization. For corporations, it means access to inexpensive labor markets; for money managers, it means access to capital markets. For the typical business traveler, it may mean something as basic as greater choice of airlines and flight times for an international trip. For an optimistic humanist, it might symbolize enhanced international cooperation and a suppression of nationalism and xenophobia. For an environmentalist, it is marred by the dangerous policies that accelerate climate change. For a technocrat, it seems the obvious economic approach to accompany the paradigm of social-media-fueled connectedness, data collection, surveillance, and targeted marketing.

There has been much discussion lately of whether the COVID-19 pandemic will spell the end of globalization. It’s hard to get economists to agree on the meaning of the numbers, or foreign policy analysts to commit to a vision of the future in a world that changes from one moment to the next. Globalization means different things to different people and entities. Its many facets, and many narratives about those facets, complicate discussion about either a contraction or a resurgence of globalization. For corporations, it means access to inexpensive labor markets; for money managers, it means access to capital markets. For the typical business traveler, it may mean something as basic as greater choice of airlines and flight times for an international trip. For an optimistic humanist, it might symbolize enhanced international cooperation and a suppression of nationalism and xenophobia. For an environmentalist, it is marred by the dangerous policies that accelerate climate change. For a technocrat, it seems the obvious economic approach to accompany the paradigm of social-media-fueled connectedness, data collection, surveillance, and targeted marketing.

Regardless of what we talk about when we talk about globalization, most of the articles that I have seen over the past few weeks have posited that the coronavirus will mean the end of the current wave, just as the Spanish flu epidemic halted the wave of globalization that steamships, trains, and the telegraph ushered in. Soldiers returning home from fighting in World War I in 1918 helped to spread it. Nationalists’ fears of literal foreign “contagion” are not entirely unfounded, as the ease of international travel has certainly facilitated the spread of the current outbreak. The predicted reversal of globalization appears to be a sensible conclusion, as it would simply reflect the implosion of financial markets, shutdown of borders, grounding of planes, and freezing of lines of trade. Will it last, though?

Stephen M. Walt, professor of international relations at Harvard, writes a “realist’s guide” to the outbreak on the Foreign Policy website, suggesting that the realist approach, while it has had little to say in the past about public health or pandemics, may still shed some light on the future of globalization. Read more »

1. As the coronavirus continues to disrupt human life in many corners of the globe, a phrase from George Frideric Handel’s Messiah has wormed its way through the background noise of my attention span. It occurs in a Part III

1. As the coronavirus continues to disrupt human life in many corners of the globe, a phrase from George Frideric Handel’s Messiah has wormed its way through the background noise of my attention span. It occurs in a Part III  We get half a sunny day every other day since Corona has coaxed us to quit public spaces. In the past fortnight or so, sunlight has been in short supply just as masks, disinfectant spray and toilet paper. When the sun is out, it’s no ordinary gift; it brings a rush of joy that wipes out not only the free-floating, dystopic COVID -19 anxiety, but also the other recent traumas we’ve faced as a family. Indoors, socially-distant by three feet, hunched over our phones for news of loved ones, we forget it is spring, but mornings the sunlight hits the windows feel as if God has turned on the power-wash setting: one is shocked into vigor, tricked into optimism. On such a day, I step down the patio threshold as if pulled by a magnet; just out of the shower and still combing my wet hair, I’m suddenly aware of another gift— soap.

We get half a sunny day every other day since Corona has coaxed us to quit public spaces. In the past fortnight or so, sunlight has been in short supply just as masks, disinfectant spray and toilet paper. When the sun is out, it’s no ordinary gift; it brings a rush of joy that wipes out not only the free-floating, dystopic COVID -19 anxiety, but also the other recent traumas we’ve faced as a family. Indoors, socially-distant by three feet, hunched over our phones for news of loved ones, we forget it is spring, but mornings the sunlight hits the windows feel as if God has turned on the power-wash setting: one is shocked into vigor, tricked into optimism. On such a day, I step down the patio threshold as if pulled by a magnet; just out of the shower and still combing my wet hair, I’m suddenly aware of another gift— soap.

I was a minor mess in high school. Had no idea what to do with my curly hair. Unduly influenced by a childhood spent watching late ‘70s television, I stubbornly brushed it to the side in a vain attempt to straighten and shape it into a helmet à la The Six Million Dollar Man or countless B-actors on The Love Boat and Fantasy Island. I couldn’t muster any fashion beyond jeans, t-shirts, and Pumas. In the winter I wore a green army coat. In the summer it was shorts and knee high tube socks.

I was a minor mess in high school. Had no idea what to do with my curly hair. Unduly influenced by a childhood spent watching late ‘70s television, I stubbornly brushed it to the side in a vain attempt to straighten and shape it into a helmet à la The Six Million Dollar Man or countless B-actors on The Love Boat and Fantasy Island. I couldn’t muster any fashion beyond jeans, t-shirts, and Pumas. In the winter I wore a green army coat. In the summer it was shorts and knee high tube socks.

I must admit that when I first flipped through Capitalism on Edge: How Fighting Precarity Can Achieve Radical Change Without Crisis or Utopia by Albena Azmanova, it did not look too inviting. The blurbs on the jacket did nothing to reassure me, suggesting that this was yet another post-Marxist critique of greedy capitalists and their enablers. As it turns out, it is, but in a way that is more interesting than I had assumed. As soon as I started reading the Introduction, I was gripped by the lucidity of ideas and clarity of the prose. For an academic text written from the perspective of Critical Theory, this is a wonderfully direct, incisive and insightful book. One does not need to agree with all the details of the analysis to find reading it a rewarding experience.

I must admit that when I first flipped through Capitalism on Edge: How Fighting Precarity Can Achieve Radical Change Without Crisis or Utopia by Albena Azmanova, it did not look too inviting. The blurbs on the jacket did nothing to reassure me, suggesting that this was yet another post-Marxist critique of greedy capitalists and their enablers. As it turns out, it is, but in a way that is more interesting than I had assumed. As soon as I started reading the Introduction, I was gripped by the lucidity of ideas and clarity of the prose. For an academic text written from the perspective of Critical Theory, this is a wonderfully direct, incisive and insightful book. One does not need to agree with all the details of the analysis to find reading it a rewarding experience.

Sughra Raza. Mid-winter Fall. February 2020.

Sughra Raza. Mid-winter Fall. February 2020.

If you, like me, have read premodern philosophers not just for antiquarian interest but also as possible sources of wisdom, you will probably have felt a certain awkwardness. Looking for guidance or assistance in ordering our own beliefs, attitudes and actions, we inevitably run into the problem that the great thinkers of the past knew nothing about what our world would look like.

If you, like me, have read premodern philosophers not just for antiquarian interest but also as possible sources of wisdom, you will probably have felt a certain awkwardness. Looking for guidance or assistance in ordering our own beliefs, attitudes and actions, we inevitably run into the problem that the great thinkers of the past knew nothing about what our world would look like.