by Leanne Ogasawara

We should first count our blessings that Dan Brown has never written about the painting. Though I suspect such a seemingly matter-of-fact picture as Velázquez’s Las Meninas would not serve as an easy target. With no hint of the occult –nor even a whiff of the Templars– it probably wouldn’t capture his attention. And yet, despite Dan Brown’s silence, Las Meninas is one of the most highly written-about paintings in history. You’ve got to wonder what is it about the the picture that has spilled so much ink? Philosopher Michel Foucault probably has a lot to do with this flood of art historical interest, since his interpretation of the painting in his 1970 book, The Order of Things, sparked what was a tidal wave of intellectual responses. But Foucault can’t account for all the attention. In fact, just recently three high-profile books (a novel and two well-received memoirs) were published on the subject of Velázquez ,in which there is nary a mention of the great philosopher.

So, then, what is it about Las Meninas?

Considered one of the greatest masterpieces in the Western canon, in the 19th century Europeans from France and England traveled to see it as if they were going on a pilgrimage. In those days, Spain was well off the beaten track and infrastructure had something to be desired. Manet, for example, was hardly able to withstand the hardships of his time in Madrid (practically starving to death he claimed)–but like walking the Compostela, he considered it a pilgrimage. One suffered– but did so in the hope of greater understanding. Manet would go on to feel transformed by his time in Madrid and considered Velázquez to be the greatest painter of all time. It is a fact that to see the significant works by Velázquez, you will need to travel to Madrid. The same can be said for Bosch and to some extent for Titian. One must make the pilgrimage to the Prado to see really understand these artists. I would add that the Louvre could learn a thing or two from the Prado, whose staff strictly enforces a no-photography rule, while continuously hissing at visitors for lowered voices. It all contributes to the heightened reality of a visit to the Prado.

Like many of the greatest works by Velázquez Las Meninas began its life hidden away in the Spanish royal palace, where not many people were given the chance to see it. For awhile it was hanging in the bedroom of one of the Hapsburg princesses; before it was then moved to the palace dining room, where it was seen hanging near another painting that it would share a wall with it for around a hundred years, Titian’s incomparable Charles V at the Battle of Mühlberg. Both pictures were spared certain death by fire in 1734 when they were unceremoniously flung out the palace second story window during a huge conflagration that burnt the alcazar to the ground. This eventually led to the building of the Prado museum; which opened to the public in 1819. Visitors began trickling in to this “least known of museums” and this was the beginning of the Prado’s almost religious mystique. Guidebooks went as far as to describe the museum as “a shrine of secular, spiritual enlightenment.” Such was the magnetic draw of the paintings by Velázquez that in 1899 all his major work was put on display in the museum’s central gallery, called the Sala Velázquez. Carved off this central gallery of Sala Velázquez, Las Meninas was given its own room. And this was how it was displayed until 1970.

Like many of the greatest works by Velázquez Las Meninas began its life hidden away in the Spanish royal palace, where not many people were given the chance to see it. For awhile it was hanging in the bedroom of one of the Hapsburg princesses; before it was then moved to the palace dining room, where it was seen hanging near another painting that it would share a wall with it for around a hundred years, Titian’s incomparable Charles V at the Battle of Mühlberg. Both pictures were spared certain death by fire in 1734 when they were unceremoniously flung out the palace second story window during a huge conflagration that burnt the alcazar to the ground. This eventually led to the building of the Prado museum; which opened to the public in 1819. Visitors began trickling in to this “least known of museums” and this was the beginning of the Prado’s almost religious mystique. Guidebooks went as far as to describe the museum as “a shrine of secular, spiritual enlightenment.” Such was the magnetic draw of the paintings by Velázquez that in 1899 all his major work was put on display in the museum’s central gallery, called the Sala Velázquez. Carved off this central gallery of Sala Velázquez, Las Meninas was given its own room. And this was how it was displayed until 1970.

Older Scholars and art lovers who saw the painting hanging alone in this alcove off the Sala Velázquez are on record describing the effect the room had on their viewing of the picture. I wanted so much to experience something like that–despite the fact that the painting has since been moved and is now held in the position of honor in the hexagonal room at the center of the Prado, along with the other major works by the painter. This room is ground zero of the Prado, with all other galleries radiating from the center of what can only be understood as the sanctum sanctorum.

I knew that visiting the Prado would be an important event in my life– and I wanted to badly to experience Las Meninas in the way the older scholars had.

But how to be alone with the work? For that was crucial: being alone with Las Meninas.

So, I made a plan. Becoming a “Friend of the Prado” set me back $100 but allowed me to enter through the Puerta de Los Jerónimos at nine sharp every day. That gave me maybe a 15 minute head start of non-ticket holders, whom I referred to as “the enemies.” The real trick for my success, though, was committing to memory the museum layout beforehand so I could make a beeline to the painting the moment I dashed through the doors. I never had to really push or shove since it took the enemies some thirty minutes before making it up to the center gallery. And by then, I had had more than my fill of being alone with Las Meninas. Blocking out the other pictures from my eyeballs, I attempted to recreate what I had read about Sala Velázquez. And turning into the gallery, I stopped and beheld the masterpiece. Like countless other viewers before me, I sighed aloud.

What is it about Las Meninas that captures our attention in such a big way?

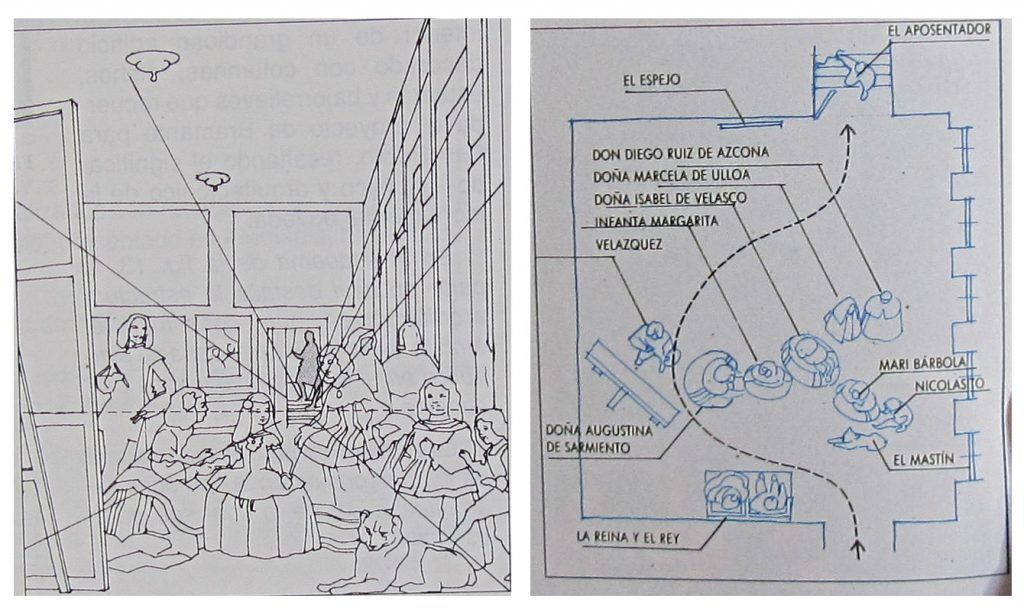

The painting gets its title from the two high-born “maids” who stand serving on either side of the little princess dressed in her white dress. And speaking of the cute little infanta, one of the friends of this blog (he knows who he is) when he saw my pictures of the painting (which I know I was not allowed to take) on Facebook said, “Oh, I know that little girl from Vienna“–Indeed, she was to be married to the future Holy Roman Emperor Leopold of Austria and three portraits of her remain today in the Kunsthistorisches Museum by Velázquez. It is sad to think that this beautiful little princess would die so young in Austria, only twenty-one years old. Fortunately, she is made eternal not just in paintings but also in the short story by Oscar Wilde, inspired by the image of the little princess he saw in the painting by Velázquez. But even more than the princess, isn’t it the two “maids” surrounding the infanta that most cause us to delight? One kneeling so prettily is handing the infanta a little red vessel –could that be sipping chocolate from the New World? With flowers in their hair and the elegant positions of their hands, they do make a vision to behold. Of course, there are also the dwarfs and and the mastiff, drawn so realistically–and yes, also respectfully (for Velázquez was known for his portraits of court jesters).

The painting gets its title from the two high-born “maids” who stand serving on either side of the little princess dressed in her white dress. And speaking of the cute little infanta, one of the friends of this blog (he knows who he is) when he saw my pictures of the painting (which I know I was not allowed to take) on Facebook said, “Oh, I know that little girl from Vienna“–Indeed, she was to be married to the future Holy Roman Emperor Leopold of Austria and three portraits of her remain today in the Kunsthistorisches Museum by Velázquez. It is sad to think that this beautiful little princess would die so young in Austria, only twenty-one years old. Fortunately, she is made eternal not just in paintings but also in the short story by Oscar Wilde, inspired by the image of the little princess he saw in the painting by Velázquez. But even more than the princess, isn’t it the two “maids” surrounding the infanta that most cause us to delight? One kneeling so prettily is handing the infanta a little red vessel –could that be sipping chocolate from the New World? With flowers in their hair and the elegant positions of their hands, they do make a vision to behold. Of course, there are also the dwarfs and and the mastiff, drawn so realistically–and yes, also respectfully (for Velázquez was known for his portraits of court jesters).

In the far back of the picture is court chamberlain José Nieto, who is pictured standing in the doorway at the back of the room, pausing to turn and look back–seemingly straight back at us! (Don’t forget about him since I think he holds the key to the painting!) But what to make of the artist depicting himself right smack in the center of the painting as well? Why is he staring at us in that way? Is he painting us? Or is he painting las Meninas, the painting hanging on the wall in front of us? The size of the canvas would be right. But what to make of the reflection of King Philip IV and his Queen Mariana in the mirror? Surely, the artist must be painting their portrait. And yet no extant double portrait of them by Velázquez exists today.

Perhaps it is we who are the stand-ins for the king and queen?

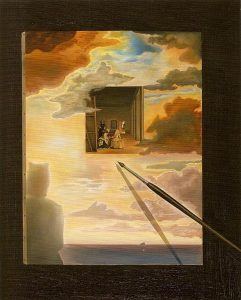

Looking at Salvador Dali’s homage to the painting (above) will bring home what is arresting about the “double gaze” of the picture.

Foucault famously declared Las Meninas to be “a painting about painting” and therefore a “representation of representation.” From his reading of Heidegger, Foucault explored what he called the episteme. This was always Foucault’s primary interest: to try and grasp the a priori grid of meaning that we map onto the world. He felt that Las Meninas, by consciously playing around with self-reflection, illuminated a more modern paradigm of being and the world. Indeed, Foucault felt that Las Meninas was the first modern picture. (He paired Las Meninas, as many people do, with the novel Don Quixote. For more on this see my post A Novel to Cross a Desert With)

Ah Michel Foucault, don’t you love him?

Ah Michel Foucault, don’t you love him?

But Velázquez scholar Jonathan Brown doesn’t see the painting in these terms at all. His theory is more common-sensical. Suggesting that there are no hidden meanings or codes in the painting at all; he sees Las Meninas as having been completed AFTER Velázquez had been given the knighthood that he had so long coveted, making Las Meninas a thank you to the king for this honor. One can see the red cross of the Knights of Santiago on the tunic of the painter as he stands back from the easel in the picture. Legend had it that King Philip IV drew the red cross in on the painting himself after Velázquez’ death to honor his favorite painter; but Brown sees no real evidence for this. Brown also suggested that at the time the work was created, a debate was happening in art circles about whether color or drawing was the most important factor in judging a masterpiece. Brown wonders if Velázquez wasn’t weighing in on the matter in Las Meninas; partial as he always was to that greatest master of color, Titian.

In the end, while the ideas are fascinating from a philosophical point of view, they don’t go very far in explaining the great power this painting holds over our imaginations. And this is where the two memoirs I read really helped me in understanding my own feelings about the picture. The picture has multiple vanishing points, such that the nine people seem to exist there in a kind of suspended animation. It is absolutely arresting. One wonders where all the vanishing points of the painting would meet if connected. Picasso and Dali also explored the issue of the lines in the painting. Surprisingly, the lines meet neither in the person of the infanta nor in that of the painter. They don’t even meet in at the king and queen–but instead all the lines seem to converge he says, around that of the departing chamberlain, José Nieto, who stands in the doorway at the back of the room. Could this be the “central figure” of Las Meninas? Traditionally the lines in Renaissance paintings converged on the figure of Christ or on the Host; while in Las Meninas, they loosely hover around the open door in the back of the room. Michael Jacobs in his moving memoir Journey into a Painting writes about the picture after receiving a death sentence from a cancer diagnosis. He ends his book focusing on that open doorway, wondering if the departing Chamberlain is not a kind of Charon figure; beckoning from across the River Styx and the beyond after death. I was recently fascinated to see that American photographer Joel Peter Wilkins also seems to highlight the departing chamberlain by turning him into a Christ figure– another symbol of death and rebirth (see left). The man at the doorway is central. And yet, all the figures in the picture– dwarf, mastiff, painter, king, queen, chamberlain, princess and two maids– I know we are all there as well–all form a perfect puzzle, in which each piece matters crucially. An unforgettable world-opening masterpiece, I can well understand why Jacobs found solace in recalling the details of its vision as he lie dying. And I too feel as if the picture is imprinted upon my eyes and heart.

In the end, while the ideas are fascinating from a philosophical point of view, they don’t go very far in explaining the great power this painting holds over our imaginations. And this is where the two memoirs I read really helped me in understanding my own feelings about the picture. The picture has multiple vanishing points, such that the nine people seem to exist there in a kind of suspended animation. It is absolutely arresting. One wonders where all the vanishing points of the painting would meet if connected. Picasso and Dali also explored the issue of the lines in the painting. Surprisingly, the lines meet neither in the person of the infanta nor in that of the painter. They don’t even meet in at the king and queen–but instead all the lines seem to converge he says, around that of the departing chamberlain, José Nieto, who stands in the doorway at the back of the room. Could this be the “central figure” of Las Meninas? Traditionally the lines in Renaissance paintings converged on the figure of Christ or on the Host; while in Las Meninas, they loosely hover around the open door in the back of the room. Michael Jacobs in his moving memoir Journey into a Painting writes about the picture after receiving a death sentence from a cancer diagnosis. He ends his book focusing on that open doorway, wondering if the departing Chamberlain is not a kind of Charon figure; beckoning from across the River Styx and the beyond after death. I was recently fascinated to see that American photographer Joel Peter Wilkins also seems to highlight the departing chamberlain by turning him into a Christ figure– another symbol of death and rebirth (see left). The man at the doorway is central. And yet, all the figures in the picture– dwarf, mastiff, painter, king, queen, chamberlain, princess and two maids– I know we are all there as well–all form a perfect puzzle, in which each piece matters crucially. An unforgettable world-opening masterpiece, I can well understand why Jacobs found solace in recalling the details of its vision as he lie dying. And I too feel as if the picture is imprinted upon my eyes and heart.

For more:

Part One of this Post is: A Novel to Cross a Desert With

Don Quixote Diaries Michel Foucault

Also Eyes Swimming with Tears and A Novel to Cross a Desert With

Also recommended:

Laura Cummings: Vanishing Velasquez (I have read it four times!!)

Everything is Happening: Journey into a Painting, by Michael Jacobs

Jonathan Brown: In the Shadow of Velasquez

Another moving book about a picture: The Angel on the Left Bank: The Secrets of Delacroix’s Parisian Masterpiece

++

Below: Provoking the spectator. “Las Meninas” by Joel Peter Witkin