by Joseph Shieber

Bertolt Brecht, the German poet and playwright, was born on this day 122 years ago, February 10, 1898.

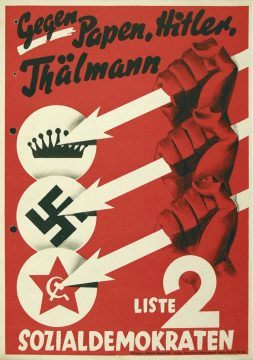

Fearing persecution by the Nazis for his writing and leftist political views, Brecht left Germany in February 1933, shortly after Hitler assumed the German Chancellorship.

At the time that he wrote the poem “Frühling 1938 / I”, Brecht was living in exile on the Danish island of Fyn.

Frühling 1938 / I (German)

Heute, Ostersonntag früh

Ging ein plötzlicher Schneesturm über die Insel.

Zwischen den grünenden Hecken lag Schnee. Mein junger Sohn

Holte mich zu einem Aprikosenbäumchen an der Hausmauer

Von einem Vers weg, in dem ich auf diejenigen mit dem Finger deutete

Die einen Krieg vorbereiteten, der

Den Kontinent, diese Insel, mein Volk, meine Familie und mich

Vertilgen mag. Schweigend

Legten wir einen Sack

Über den frierenden Baum.

Spring 1938 / I (English)

Today, early Easter Sunday

A sudden snowstorm came over the island.

Snow lay between the budding bushes. My young son

Brought me to an apricot sapling at the house wall,

Away from a verse in which I pointed with my finger at those

Who prepared a war that may well mean, for

The continent, the island, my people, my family and me,

Extermination. Silent

We placed a sack

Over the freezing tree.

Translation: Joseph Shieber

Some months ago, on a sunny Sunday afternoon, I went to my bank’s ATM in the main market close to where I live in the Defence Housing Authority, Lahore’s latest fancy suburb, which is organized and managed by the military.

Some months ago, on a sunny Sunday afternoon, I went to my bank’s ATM in the main market close to where I live in the Defence Housing Authority, Lahore’s latest fancy suburb, which is organized and managed by the military.

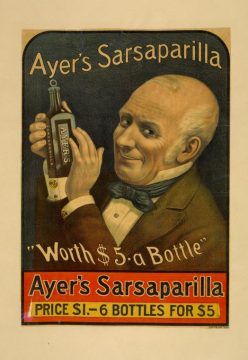

The wine community is often accused of being snobby and elitist. The language used to describe wine is one source of this innuendo. Although most people have become accustomed to the fruit descriptors used in wine reviews, when wine writers wax poetic by describing wines as “graphite mixed with pâte de fruit”, even

The wine community is often accused of being snobby and elitist. The language used to describe wine is one source of this innuendo. Although most people have become accustomed to the fruit descriptors used in wine reviews, when wine writers wax poetic by describing wines as “graphite mixed with pâte de fruit”, even

I first heard Motörhead in 1988. I was a DJ at

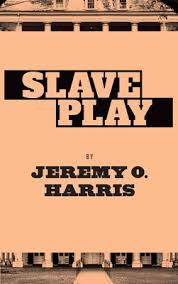

I first heard Motörhead in 1988. I was a DJ at  Jeremy Harris is a dark and stormy cocktail of Dave Chappelle, Augusto Boal, Boots Riley, and James Baldwin. The dark comedic energy that drives Slave Play, Harris’s provocative Broadway show about racism, sex, kinky fetishism, white supremacy, interracial relationships, slavery, the Antebellum South, post-colonialism, and psycho-sexual drama therapy, is the sort that makes you cry while laughing, tremble with anxiety, giggle from embarrassment, and question the sources of your own laughter. Slave Play riffs darkly on how black and white people in America live intimately together yet are essentially apart. Carrying the historical burdens of slavery and white supremacy into the 21st century, Harris shines a dark therapeutic light onto areas of our racial relations that are vibrating with pain and festering with pleasure.

Jeremy Harris is a dark and stormy cocktail of Dave Chappelle, Augusto Boal, Boots Riley, and James Baldwin. The dark comedic energy that drives Slave Play, Harris’s provocative Broadway show about racism, sex, kinky fetishism, white supremacy, interracial relationships, slavery, the Antebellum South, post-colonialism, and psycho-sexual drama therapy, is the sort that makes you cry while laughing, tremble with anxiety, giggle from embarrassment, and question the sources of your own laughter. Slave Play riffs darkly on how black and white people in America live intimately together yet are essentially apart. Carrying the historical burdens of slavery and white supremacy into the 21st century, Harris shines a dark therapeutic light onto areas of our racial relations that are vibrating with pain and festering with pleasure.

Zanele Muholi. Ntozakhe II, Parktown, Johannesburg. 2016.

Zanele Muholi. Ntozakhe II, Parktown, Johannesburg. 2016.

Yesterday was James Joyce’s birthday. His one-hundred-and-thirty-seventh. Or would have been, if he hadn’t died, in Zurich, in January 1941, but were instead swelling the ranks of the current generation of supercentenarians, their increasing longevity bedeviling the demographics departments of local life insurers. Joyce is buried in Fluntern Cemetery on Mount Zurich, his grave marked by a wry-looking seated effigy, like a jocular, unaccommodated Lincoln Memorial; he is further commemorated in the eccentric orthography of the names of the city’s two rivers, the Limmat and the Sihl, in a plaque mounted on the point at which they diverge downstream from the Swiss National Museum, where the letter “i” in both names has been replaced with a “j”.

Yesterday was James Joyce’s birthday. His one-hundred-and-thirty-seventh. Or would have been, if he hadn’t died, in Zurich, in January 1941, but were instead swelling the ranks of the current generation of supercentenarians, their increasing longevity bedeviling the demographics departments of local life insurers. Joyce is buried in Fluntern Cemetery on Mount Zurich, his grave marked by a wry-looking seated effigy, like a jocular, unaccommodated Lincoln Memorial; he is further commemorated in the eccentric orthography of the names of the city’s two rivers, the Limmat and the Sihl, in a plaque mounted on the point at which they diverge downstream from the Swiss National Museum, where the letter “i” in both names has been replaced with a “j”.

Banners waved, the converted preached and hawkers peddled hats, buttons, “Impeach This” sweatshirts and dodgy conspiracy theories. T

Banners waved, the converted preached and hawkers peddled hats, buttons, “Impeach This” sweatshirts and dodgy conspiracy theories. T Welcome to Des Moines, where unmarked satellite trucks troll snowy streets, coffee houses and hotel lobbies are broadcast-ready, and legions of reporters and crew and a few political tourists have swept up and besieged an entire town.

Welcome to Des Moines, where unmarked satellite trucks troll snowy streets, coffee houses and hotel lobbies are broadcast-ready, and legions of reporters and crew and a few political tourists have swept up and besieged an entire town.