by Brooks Riley

by Brooks Riley

by Sarah Firisen

First off, let me just get this out of the way: we share too much data about ourselves knowingly with companies and they collect, use and share even more than most of us are aware of (read through those lengthy privacy notices recently?). And unless you live in Europe with its pretty extensive GDPR rules, or California with its new data privacy laws, odds are, the government isn’t going to do much to regulate that anytime soon. And we all sort of know this, and tell ourselves that it’s the price we have to pay, “The rise of surveillance capitalism over the last two decades went largely unchallenged. ‘Digital’ was fast, we were told, and stragglers would be left behind. It’s not surprising that so many of us rushed to follow the bustling White Rabbit down his tunnel into a promised digital Wonderland where, like Alice, we fell prey to delusion. In Wonderland, we celebrated the new digital services as free, but now we see that the surveillance capitalists behind those services regard us as the free commodity.”

First off, let me just get this out of the way: we share too much data about ourselves knowingly with companies and they collect, use and share even more than most of us are aware of (read through those lengthy privacy notices recently?). And unless you live in Europe with its pretty extensive GDPR rules, or California with its new data privacy laws, odds are, the government isn’t going to do much to regulate that anytime soon. And we all sort of know this, and tell ourselves that it’s the price we have to pay, “The rise of surveillance capitalism over the last two decades went largely unchallenged. ‘Digital’ was fast, we were told, and stragglers would be left behind. It’s not surprising that so many of us rushed to follow the bustling White Rabbit down his tunnel into a promised digital Wonderland where, like Alice, we fell prey to delusion. In Wonderland, we celebrated the new digital services as free, but now we see that the surveillance capitalists behind those services regard us as the free commodity.”

This is all even true of my boyfriend, who deludes himself with the belief that because he’s not on Facebook, Twitter etc., he has some privacy, but doesn’t acknowledge that by having an Amazon account and using Pinterest, he’s already lost that battle. Indeed, he has a mobile phone and an iPad, so he probably would have lost that battle without an Amazon account. When I mention this to him, and tell him what I’m going to be writing about here, he does say something very wise, “why do they send me adverts after I’ve bought it online?”

And this question goes to the heart of what is irritating me today: I may have lost the battle over data privacy, but why is it so hard for these companies to at least do something with my data that benefits me, and them? And so, I come to the Sephora Syndrome. Read more »

by Dave Maier

Another not-necessarily-the-best-of-the-year mix, but there do seem to be a number of 2019 releases. Warning: this one’s pretty drony, so don’t be driving or anything. Sequencers next time, I promise! (A few anyway.)

Another not-necessarily-the-best-of-the-year mix, but there do seem to be a number of 2019 releases. Warning: this one’s pretty drony, so don’t be driving or anything. Sequencers next time, I promise! (A few anyway.)

0:00 Anne Chris Bakker – Norge Svømmer (Reminiscences [Dronarivm])

4:50 FRAME – Earth (The Journey [Glacial Movements])

12:30 Strom Noir – There will never be another you (va/Illuminations II [Dronarivm])

17:30 Kinephilia – Nothing really

21:20 tsone – a good cleansing always sets one’s mind to rights (pagan oceans I [Home Normal])

26:00 Joseph Branciforte & Theo Bleckmann – 5.5.9 (LP1 [greyfade])

34:20 Le Berger – 0003 [No thanks to you] ( Sounds of the Sleepless Sam v.1)

40:40 Silent Vigils – Mossigwell (Fieldem [Home Normal])

51:00 Forrest Fang – The Other Earth (Ancient Machines [Projekt])

1:00:30 end

Further info about this mix’s music in a sec. First, a program note. There’s something a bit screwy about one of the tracks here. I should know, because I made it myself. It’s kind of a thought experiment (so you probably won’t be able to hear what I mean, and it shouldn’t interfere with your enjoyment), and I originally intended to finish this post with a discussion of the issues I think it raises. It got a bit out of hand though, so I think we’ll postpone that part until next time. (They’re really great issues though, so that’ll be a lot of fun.)

Now back to the show.

by Bill Benzon

I’ve been binging on TwoSet Violin for the last month or so. Of course the duo is not, as my title suggests, in the business of music education. But you will learn, or be reminded of, a great deal about (mostly) classical music by listening to them. They are, rather, musical comedians – or is it comedic musicians? Whatever it is, it’s not musical comedy, which is a theatrical genre. Brett Yang and Eddie Chen met and became friends while they were still in high school in Australia. They started posting videos to YouTube in 2013, gave up their orchestral jobs in 2016, and first toured the world with a stage act in 2017. Most of what they do in their YouTube videos would not, however, transfer to stage.

On stage with Hilary Hahn

The following video, however, shows a segment from their stage act.

They undertake to play a Paganini caprice with the help of Hilary Hahn. All three are spinning hula hoops while playing.

Hilary Hahn, of course, is a top-tier classical soloist and, as such, makes her living in a cultural sphere that is far removed from the vaudeville stage, which is ultimately where this kind of act comes from. She is not a regular part of their stage act, though she has been on stage with them a number of times and has been on several of their YouTube videos. On one of those occasions she played a piece while spinning a hula hoop, which is one of the various Ling Ling challenges that show up in their videos. Read more »

by Akim Reinhardt

Stuck is a weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday through early April. The Prologue is here. The table of contents with links to previous chapters is here.

You’ve been an on-again, off-again working band for a decade. During that period there have been numerous breakups and seemingly endless lineup changes. Then, after years of grinding and uncertainty, you finally hit it big in 1975. You earned it.

You’ve been an on-again, off-again working band for a decade. During that period there have been numerous breakups and seemingly endless lineup changes. Then, after years of grinding and uncertainty, you finally hit it big in 1975. You earned it.

But you’re also riding a larger cultural wave; you’ve been assigned to a niche, what people are now calling Southern Rock, a sub-genre that your band pre-dates.

So be it. You worked your ass off, and now you’ve arrived. You get signed to a major label. Your eponymous debut album goes gold. You have a single that does okay. You have a nickname; the frequently shuffling roster somehow ended up with a trio of guitarists, and you’ve been dubbed the “Florida Guitar Army.” And you have an opus. The last song on your new album is worthy of your genre predecessors, the Allman Brothers and Lynyrd Skynyrd. A confident, snarling intro is followed a fierce torrent of wailing guitar solos. Over nine minutes of kick ass, balls to the wall rock n roll, “Green Grass and High Tides Forever” will cement your place in Southern Rock lore.

Then it all starts to wobble. Read more »

by Gerald Dworkin

At least since Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973 the issue of Conscientious Objection (henceforth CO) has been an important one in the context of Catholic hospitals and women patients. Such hospitals object to the provision of abortions, contraceptives, sterilization, fertility care, and “gender-affirming care” such as hormone treatments and surgeries.

At least since Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973 the issue of Conscientious Objection (henceforth CO) has been an important one in the context of Catholic hospitals and women patients. Such hospitals object to the provision of abortions, contraceptives, sterilization, fertility care, and “gender-affirming care” such as hormone treatments and surgeries.

In 1973 the Church (the Senator not the institution!) Amendment was passed. This stated that individuals in institutions receiving federal funds may not be required to perform sterilization or abortions contrary to their religion or conscience. No such individual shall be required to perform or assist in any health service program or research activity if such program or activity was contrary to his religious beliefs or moral convictions.

In 1997 when Medicare Advantage was passed it included a restriction that no such plan, nor any Medicaid-managed plan, was required to “provide, reimburse for, or provide coverage of a counseling or referral service if the organization objected to the service on moral or religious grounds.”

In 2010 the Patient Protection and Affordable Care act said a State could prohibit abortion in qualified health plans. It also introduced a new restriction. Government-funded institutions may not discriminate against individuals or institutions on the basis that such institutions do not provide any health care item or service for the purpose of causing, or for assistance in causing, the death of any individual such as by assisted-suicide. Read more »

by Jonathan Kujawa

As I’ve tried to convey over the years here at 3QD, mathematics is the bee’s knees. Like most apologias for mathematics, many of my essays tend to fall into one of two categories.

The extrinsic: on math’s usefulness in real-world applications like internet searches, GPS technology, compression and recovery of images, encryption, the handling of large data, and the like. This is the reason my relatives (and most of my students) think math is worth learning.

The intrinsic: on math’s beauty, universality, timelessness, ability to amaze and inspire awe, its endless depth and richness, and its ability to spark joy and fun. This is what drew me (and some of my students) to study math and still motivates me today to teach and do research.

But there is a third quality of mathematics which I’ve never quite been able to articulate. I’ve only managed to sneak up on it from time-to-time. This is the humanity of mathematics. For some, humanity may seem more the purview of literature, music, art, psychology, sociology, or philosophy. Not mathematics. They would be wrong, though. Read more »

flames are the feathers of this bird

but I’m not calling the fire brigade

—life burns life

this is a particular bird

whose flame is multitudinous red

with flamboyant nuance:

high-frequency colorwheels thrown in

and well-played purple notes of a bass line

in its wings

—but “multitudinous” fails to tell the tale

of this bonfire bird,

a bird blown by algorithmic winds

at the keystrokes of a friend

lands blazing on my screen and sits

—this birdblaze with redgold beak

sharper than human wit

what do you say when a thing like this comes to light

which exceeds sunshine acid visions?

makes them lame

how to state the spectral luxury of this bird,

to see it, out on a limb, its satiating color

which some pure mind has wrought?

I could say, “Rufous-Backed Kingfisher”

or “Ceyx rufidorsa”

but how to really say it?

how to paint it?

how to see it?

how to hold it in mind’s eye?

don’t try, begin

.

Jim Culleny

12/11/18

by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

One way to think about argument is to think of it as a fight. In fact, it’s the default interpretation of how things went if someone reports that they’d had an argument with a neighbor or a colleague. If it’s an argument, that means things got sideways.

In logic, though, arguments are distinguished from fights and quarrels. Arguments, as collections of claims, have a functional feature of being divisible into premises and conclusions (with the former supporting the latter), and they have consequent functional features of being exchanges of reasons for the sake of identifying outcomes acceptable to all. So arguments play both pragmatic and epistemic roles – they aim to resolve disagreements and identify what’s true. The hope is that with good argument, we get both.

If argument has that resolution-aspiring and truth-seeking core, is there any room for adversariality in it? There are two reasons to think it has to. One has to do with the pragmatic background for argument – if it’s going to be in the service of establishing a resolution, then the resolved sides must have had fair and complete representation in the process. Otherwise, it’s resolution in name only. That seems clear.

The second reason has to do with how reasons work in general. Read more »

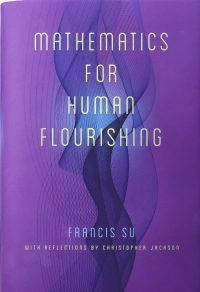

by Elizabeth S. Bernstein

The United States continues to be virtually the only developed country which does not guarantee any paid time off work to new parents. A study recently released by the New America think tank explores the “complicated, confusing, and uneven leave landscape for workers,” and the behaviors that result. The federal Family and Medical Leave Act entitles workers only to unpaid time off, and many employers and workers do not fall even within that mandate. While some employers, and public insurance programs in some states, do offer paid family leave, such benefits were found less likely to be available to lower-income households and to workers without college degrees.

The United States continues to be virtually the only developed country which does not guarantee any paid time off work to new parents. A study recently released by the New America think tank explores the “complicated, confusing, and uneven leave landscape for workers,” and the behaviors that result. The federal Family and Medical Leave Act entitles workers only to unpaid time off, and many employers and workers do not fall even within that mandate. While some employers, and public insurance programs in some states, do offer paid family leave, such benefits were found less likely to be available to lower-income households and to workers without college degrees.

According to the New America researchers, nearly half of the parents they surveyed reported taking no leave after the birth or adoption of a child. The weight of this finding is underscored by the definition the researchers used for “leave” – namely, anything “more than a day or two off work,” paid or unpaid. The mothers and fathers who reported taking no leave had not, in other words, taken even three days off work.

As documented in a previous report from New America, job-protected paid family leaves are associated with improved physical and mental health for both children and parents. This new research could therefore serve as yet another reminder of the deleterious effects of the family leave policies we have had, and continue to have, in the United States.

What a shame then, to see the study treated as if its primary contribution was to have turned up a previously unappreciated form of gender discrimination. The headline in HuffPost was this: “Even When Men Take Parental Leave, They’re Paid More, New Study Finds.” Great click-bait, and also completely misleading. Read more »

by Anitra Pavlico

My experience is what I agree to attend to. —William James

While you might not break into a neighbor’s house to log onto your Facebook account if your internet were down, a case can be made that many of us are victims of at least a moderate behavioral addiction when it comes to our smartphones. At the playground with our kids, we’re on our phones. At dinner with friends, we’re on our phones. In the middle of the night. At the movies. At a concert. At a funeral. (I was recently at a memorial service for my friend’s mother, and someone’s cell phone rang during my friend’s reminiscence.)

While you might not break into a neighbor’s house to log onto your Facebook account if your internet were down, a case can be made that many of us are victims of at least a moderate behavioral addiction when it comes to our smartphones. At the playground with our kids, we’re on our phones. At dinner with friends, we’re on our phones. In the middle of the night. At the movies. At a concert. At a funeral. (I was recently at a memorial service for my friend’s mother, and someone’s cell phone rang during my friend’s reminiscence.)

In his recent book Digital Minimalism [1], Cal Newport argues that we need a philosophy for how to approach the use of digital technology. Ad-hoc measures such as disabling notifications and installing apps that monitor our screen time are missing the point. Instead of working backward from an immersion, Newport says, we should examine our lives without technology first and figure out how technology can serve our values and interests in the least intrusive way. Unlike digital maximalists, who try every new app and gadget and try to shoehorn them into their lives, digital minimalists ruthlessly screen each new tool before using it. Newport portrays maximalism as the technology philosophy that “most people deploy by default–a mind-set in which any potential for benefit is enough to start using a technology that catches your attention.” Read more »

Michelle M. Le Beau, Arthur and Marian Edelstein Professor of Medicine, is a leading authority in hematologic malignancies. Her groundbreaking research led to the identification of the recurring cytogenetic abnormalities in hematological malignant diseases, in defining the clinical, morphological, and cytogenetic subsets of leukemias and lymphomas, and in identifying the genetic pathways that lead to myeloid leukemias. She is currently a member of the Board of Directors of the American Association for Cancer Research, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society and the American Society of Hematology. Her current research focus is on therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia.

Azra Raza, author of The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, oncologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University, and 3QD editor, decided to speak to more than 20 leading cancer investigators and ask each of them the same five questions listed below. She videotaped the interviews and over the next months we will be posting them here one at a time each Monday. Please keep in mind that Azra and the rest of us at 3QD neither endorse nor oppose any of the answers given by the researchers as part of this project. Their views are their own. One can browse all previous interviews here.

1. We were treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 7+3 (7 days of the drug cytosine arabinoside and 3 days of daunomycin) in 1977. We are still doing the same in 2019. What is the best way forward to change it by 2028?

2. There are 3.5 million papers on cancer, 135,000 in 2017 alone. There is a staggering disconnect between great scientific insights and translation to improved therapy. What are we doing wrong?

3. The fact that children respond to the same treatment better than adults seems to suggest that the cancer biology is different and also that the host is different. Since most cancers increase with age, even having good therapy may not matter as the host is decrepit. Solution?

4. You have great knowledge and experience in the field. If you were given limitless resources to plan a cure for cancer, what will you do?

5. Offering patients with advanced stage non-curable cancer, palliative but toxic treatments is a service or disservice in the current therapeutic landscape?

by Tim Sommers

What if most speech is worthless? Or, rather, what if most speech that purports to count as a contribution to “free expression” is mostly worthless? Take the internet. What’s on it? Lots of great information and great journalism and even art. But, also, pornography. Lots of pornography. Between 15% and 80% of net traffic is porn, depending on which study you believe. But if you count semi-nude pictures, it’s got to be at least…well, a lot. Lots of cat pictures, too. Then there are the blogs and comment threads and likes and dislikes. Even where these are about significant topics, most of opinions expressed are repetitive assertions of a fairly narrow range of already well-known opinions. And then there’s the insults, the invectives, and general nastiness. I am not against porn. I am not even against insults per se. What I wonder though is, whatever value porn, for example, has for you, or whatever expressive relief you get from typing insults, should we think that these things ought to count as worthy the high value and high level of protection we ordinarily afford free speech? Maybe. Maybe, not.

There seems to be a lot of agreement that “free speech” is in crisis – on campuses, on the web, or on social media. But not a lot of agreement about what the crisis is supposed to be. There seems to be a lot of agreement that regulating, or interfering in any way, with free speech is bad. But not a lot of discussion of exactly what is bad about it. It sometimes seems that “freedom of speech” is just an empty phrase to be filled in by whatever you happen to think that it would be good not to have interfered with. (Maybe, you’ve encountered the internet joke that suggest you can now argue for anything by saying “what you want to argue for” and then asserting “Because freedom!”) And so, the “crisis” sometimes seems to be just people you don’t like interfering with something you do like. (Have you ever heard of a conservative pundit complaining about a liberal speaker being “de-platformed” or vice-versa?) My point is, unless we engage with what is good or bad about freedom of speech, it’s going to be hard to evaluate what the crisis is and whether we can regulate our way out of it. So, let’s start there. Or, rather, here: What is free(dom of) speech? Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Brooks Riley

When Vienna‘s Albertina Museum exhibition of works by Albrecht Dürer ended in January 2020, it seemed quite possible that several of the masterpieces on display might never again be seen by the public, among them The Great Piece of Turf. This may sound like a dire prediction for a fragile work that is routinely exhibited every decade or so, but as the UN announced recently, we may already have passed the tipping point in the race to save our world and ourselves. A decade from now we may be too engaged in the struggle to survive to focus our attention on a small, exquisite watercolor created 500 years ago.

When Vienna‘s Albertina Museum exhibition of works by Albrecht Dürer ended in January 2020, it seemed quite possible that several of the masterpieces on display might never again be seen by the public, among them The Great Piece of Turf. This may sound like a dire prediction for a fragile work that is routinely exhibited every decade or so, but as the UN announced recently, we may already have passed the tipping point in the race to save our world and ourselves. A decade from now we may be too engaged in the struggle to survive to focus our attention on a small, exquisite watercolor created 500 years ago.

Up to now, Dürer has been one of the many diversions that have lured me away from thinking about the climate crisis. At this moment in history, when focusing on the future of the planet is required, we are deluged by distractions than didn’t exist 30 years ago when the climate warnings began to escalate. We cram our free time with clickbait high and low, binges of movies and TV shows on streaming platforms, all-you-can-hear on Spotify, endless slide shows, political sideshows, not to mention all the other interests we may have that are accessible via Google or Wikipedia. Online shopping diverts us further, feeding desires ahead of needs. The outcry of scientists and the activism of Time magazine Person of the Year Greta Thunberg have done little to pry us from our pleasures.

The climate crisis will not wait for us to put down our devices and devote serious thought or action to the issue. As a species, we react more to major events than to chronic conditions. The climate crisis is not an event, it’s a slow-rolling inevitability that will play out in differing catastrophic scenarios, to be labeled events only when they occur. Meanwhile, this gathering storm hums along in the background of our lives as we go about business as usual—not unlike death, another inevitability whose faint background noise accompanies us throughout our lives. Read more »

“May our Chinar last a thousand years,”

Grandfather said, clenching a cigar.

“Chi means What, Nar: Fire: What fire!”

Rustling boughs reigned above the tin roof

of our home where I was born a Scorpio

at midnight. It’s Fall. Each leaf burst into

a flower. We gathered the remains of dyes

to create fuel for winter, sprinkling water

on burning leaves, palms brushed ashes

together, packing cinders in a clay pot

matted in bright wicker, his kangri.

“Symbol of our culture,” he said,

cloaking it between his knees under

a loose mantle, his phiran, three yards

of brown houndstooth made by Salama,

the beloved tailor at Polo View, solely

for Grandfather who said the embers

warmed his bones. “We are all bones

under the houndstooth,” my father said.

He’s sun-withered, pouring morning tea

from a samovar alone beside an amputated

trunk. What’s father doing in Kashmir,

have they annulled the Partition?

But he still parts his hair in the center.

A Himalayan glacier ruptured its bank.

Signal towers sunk, our tin roof as well.

My valley was again a lake it used to be.

I was a shikara. I was a crewel curtain

embroidering the shikara I once was.

Barrenness had become a thousand things.

By Rafiq Kathwari / @brownpundit

by Chris Horner

In May 1919 the remains of a woman were fished from the Landwehr canal in Berlin. The three doctors available must have suspected the identity of the corpse, as they refused to perform a post mortem on it. Identification was in any case made by examination of the clothes on the body. This had been Rosa Luxemburg. She had perished essentially because the leftist uprising in Berlin, initiated by her fellow Sparticist leader Karl Liebknecht without her agreement, had failed. Luxemburg, who had fiercely criticised the Bolshevik approach to revolution as dangerously authoritarian was clubbed and then shot to death by members of the Freikorps, whose repressive violence makes them fitting antecedents to the Nazis.

The great revolutions in ‘The West’ are often seen as turning points, thresholds, new stages in history, and their very dates have a kind of resonance: 1776, 1789 (or 1794), 1917, and so on. History, of course, may make us change our minds about the degree of success, the meaning, the import of those events, but they remain potent as symbols, whatever posterity’s judgment may be. And there is a second sequence, of course, that of the failed revolutions: 1796, 1821, 1848, 1871, 1905, 1918, and 1956. These are the abortive revolutions and uprisings. This second list is the longer one, but like the successful ones, judgment about ultimate meaning, including the meaning of ‘success’ and ‘failure’, remain open to revision and reconsideration.

Of the revolutions that never were, it is the one that began in Germany in 1918 that is most relevant to Hannah Arendt. Arendt, born in 1906, married to Heinrich Blucher (an ex Sparticist) has a biography and a set of concerns defined by the fate of Germany after 1918. Rosa Luxemburg’s life and death – including the nature of the regime that connived in her murder – was the subject of an eloquent and moving essay by Arendt and published in Men in Dark Times in 1966. For all her criticism of Rosa Luxemburg’s mistakes, it is clear that she stands as a kind of exemplar for Arendt. If it had succeeded, if some kind of ‘Red’ government has seized and kept hold of power in the 1918-9 period, the effect on Germany, the nascent Soviet State in Russia, and the rest of the world would have been, one assumes, huge. But it failed, and Hitler and Stalin were the successors to that non-event. Read more »