by Akim Reinhardt

Spectator sports can reflect a society’s worst inclinations by promoting pure partisanship.

Spectator sports can reflect a society’s worst inclinations by promoting pure partisanship.

Pure partisanship is profoundly anti-intellectual. Pure partisanship can disable a person’s moral compass. Anyone who follows sports, even tangentially, witnesses this frequently. This team’s victory or that team’s loss have led to countless riots. Here in Baltimore a few years ago, I listened to fans make excuses for football player Ray Rice after footage surfaced of him knocking his fiancee unconscious. And just this past weekend, Milwaukee Brewers baseball fans gave star pitcher Josh Hader a standing ovation after it was revealed that he had published racist and homophobic tweets. My team, wrong or right.

In the world of spectator sports, unchecked partisanship reveals human beings’ self-limiting intellects and ugly moral shortcomings. But when pure partisanship runs amok in politics, the possible ramifications are truly dire. A my party (or candidate, or politician) wrong or right attitude facilitates political repression and the rise of totalitarianism. That is the threat facing the United States and several other democratic nations today.

It is a recent development. For most of the post-WWII period, American political partisanship was moderated by tremendous pressure to conform. While conformist pressures certainly present their own set of problems worthy of critique, we must acknowledge that they also helped preclude the type of hyper political partisanship we now see in the Age of Trump.

Open any U.S. History textbook, and it will talk about the long 1950s (ca. 1947-64) as an era of prosperity and conformity. That pressure to conform was rooted in both confidence and fear, in past experiences and prospects for the future.

If the Great Depression forced unwanted sacrifices upon many Americans, World War II glorified sacrifice and demanded discipline from all quarters. Afterwards, intense social pressures emanating from the Cold War cultivated and reinforced conformity. A host of external threats continually conditioned the nation’s citizenry to stay in line, follow orders, be militant, and ostracize difference.

This damaged American society in many ways. The specter of a nuclear holocaust fomented deep anxiety. Economic competition with the Soviet Union encouraged crass materialism. Competing propaganda promoted furious breast beating. And undergirding it all were episodes of real, horrific violence (Korea, Vietnam, and a panoply of smaller engagements). The second Red Scare (1947-57) was perhaps the worst of it on the homefront. Throughout its entirety, the Cold War (1947-91) was marked by looming external threats that demanded obedience and loyalty. And that in turn marginalized extreme forms of political partisanship.

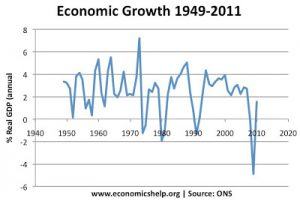

If the Cold War was the stick, then the economy was the carrot. The quarter-century following World War II was an era of unparalleled prosperity generally, and particularly for white America. The New Deal had helped, but it was the war that resoundingly ended the Great Depression. The nation’s real GDP nearly doubled between 1940-45. In 1946, it stood at $1.961 trillion. By 1973, it had nearly tripled again to $5.424T. That same year, the nation’s poverty rate reached its historic low of just over 11%.

For people who had lived through the Great Depression and WWII, even as children, it was an astonishing turnaround and cause for sincere gratitude. The white collar middle class expanded, and perhaps more importantly, masses of blue collar workers earned a middle class wage for the first and only time in American history. These successes fostered a don’t-rock-the-boat atmosphere. The nation’s economy was unfathomably healthy compared to the 1930s. Every segment of society was gaining, and that helped temper disunity; don’t fix what’s not broken, especially when we all know just how awful “broken” can be.

By the end of the 1960s, the U.S. economy had been so dominant for so long, that a new generation of Americans had been allowed to embrace a pernicious myth: the dream of some fantastic, eternal boom. Born after the war, most Baby Boomers (b. 1946-64) did not experience national economic hardship during their childhoods; regardless of their individual class standing, the national economy remained strong. Family stories of parents and grandparents suffering and sacrificing throughout the Great Depression and World War II were tales of the past. Within the Boomer subculture an illusory version of the American Dream materialized, a promise, against all reason, that each generation could and should expect to be materially better off than the prior generation. Many white Americans in particular simply expected upward mobility to be part of their birthright.

During the long 1950s, the Cold War and consistent economic prosperity contributed to a political consensus that expressed itself in several ways, as the Republican-Democratic duopoly found substantial common ground.

Beginning in 1947, fighting the Cold War was a given for both parties, and they competed to outdo each other in their public hostility towards the Soviet Union. Domestic policies also overlapped. At home, the economic theories of British economist John Maynard Keynes and his followers held sway. Keynes was a capitalist, but he eschewed the radical laissez-faire policies that had contributed to the Great Depression. The Keynesian consensus advocated reasonable regulations of business, and occasional government adjustments to the economy as a way of avoiding the boom-bust cycle that had plagued capitalism since its inception. And while Republicans favored less taxation and public spending than Democrats, neither party was shy about promoting social welfare policies designed to help strengthen the middle class, such as the GI Bill, the Interstate Highway Act, and countless state and local programs. The smooth presidential transition from Republican Dwight Eisenhower (1963-61) to Democrat John Kennedy (1961-63), and their remarkably similar foreign and domestic policies, illustrate the era’s muted partisanship.

Conservative economic ideologies had previously been thoroughly discredited by the Great Depression. During the long 1950s, few serious thinkers or American voters entertained the notion of reviving unstable laissez-faire policies. When free marketeer Barry Goldwater gained the Republican presidential nomination in 1964, he suffered a disastrous loss to Lyndon Johnson that included the most lopsided popular vote to date. And as late as 1969, Republican president Richard Nixon was believed to have said “We’re all Keynesians now.” However, change was closer than most anyone realized.

Conservative economic ideologies had previously been thoroughly discredited by the Great Depression. During the long 1950s, few serious thinkers or American voters entertained the notion of reviving unstable laissez-faire policies. When free marketeer Barry Goldwater gained the Republican presidential nomination in 1964, he suffered a disastrous loss to Lyndon Johnson that included the most lopsided popular vote to date. And as late as 1969, Republican president Richard Nixon was believed to have said “We’re all Keynesians now.” However, change was closer than most anyone realized.

By 1968, the nation was in crisis. The assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy; several years of urban riots that peaked that summer; the protests and police riot at the Democratic national convention in Chicago; the Vietnam War’s growing unpopularity; the spread of a controversial counterculture that encouraged casual sex and drug use; racist backlashes to the successes of the civil rights movement; the emergence of various ethnic and gender protest movements; and the first signs of de-industrialization and economic decline: all of these tested the nation’s unity.

During the 1970s, the first cracks in a dominant U.S. economy appeared. Starry eyed expectations soon ran headlong into 1970s staglfation: high rates of unemployment and inflation. De-industrialization cutoff a major path for blue collar workers to enter middle class.

Democratic Party control of the White House (all but eight years from 1933-69) yielded to GOP dominance. Republicans held the presidency from 1969-1992, save for Jimmy Carter’s one term (1977-81), and even that was only possible because of Nixon’s Watergate scandal. And it was the Republicans who had offered a home to the small cadre of marginalized conservatives during the long 1950s. Now, as the GOP crested, a new coalition of religious, economic, and foreign policy Conservatives moved front and center. The Keynesian consensus, developed by the generations who had endured depression and world war, unraveled.

In 1981, nearly fifty years after Herbert Hoover was hounded from the White House in disgrace, Ronald Reagan rode into office upon a Conservative wave. Republicans began dismantling America’s carefully crafted safeguards on capitalism. It didn’t work at first. But then it did. And then it didn’t. The U.S. economy returned to a boom-bust cycle. By the 1980s, the Keynesian consensus that had helped unify Americans was in tatters. A decade later, unifying Cold War ideologies also evaporated.

Bot parties had internal divisions about the specifics of Cold War strategy. In both camps, some favored cautiously and modestly improved relations (detente), while others were more hawkish. But either way, important consistencies persisted. The vast majority of Americans framed the Soviet Union and its communist system as dangerous competition. Policy differences merely reflected disagreements on the best way to prosecute the Cold War. So long as the Cold War carried on, Americans could rally around a form of nationalism that loudly championed freedom and prosperity, and condemned communism generally and the USSR specifically.

Then, at the end of 1991, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics collapsed. Increasingly acrimonious partisanship emerged as the nation’s unifying ideologies slipped into the ether.

The common sacrifices of World War II were now many decades past. They Cold War and Keynesian consensus, which had helped unite Americans and tamper down partisanship, were no more. The Cold War’s end meant the end of a common driving purpose. The end of America’s unrivaled economic dominance led to disagreements about what had caused the decline and how to reverse it. Blue collar Americans in particular were often unmoored. The cherished fantasy of an American Dream that only moves forward was upended. And unresolved social and cultural tensions from the upheaval of the 1960s presented opportunistic politicians a road map for exploiting fears and anger. New forms of political intolerance and extremism emerged.

Congressional Republicans, so long in the minority, led the new partisan charge. Newt Gingrich’s Republicans introduced a level of partisan rancor to the House that had not been seen since the 19th century. Later, Republicans Trent Lott and Mitch McConnell followed suit in the Senate. In the mass media, an army of right wing radio talk show hosts led by Rush Limbaugh spewed lies and bile dressed up as patriotism. Fox News emerged as a refined propaganda machine on television. And the Democratic Party acted as enablers.

As the GOP tracked rightward, instead of successfully fighting back, national Democrats also slid to the right. Rather than standing up for their progressive vision, they compromised, pursuing a phantom version of the old consensus. Bill Clinton became the first Democrat elected to two-terms since Franklin Roosevelt. He did so by abandoning much of FDR’s New Deal and by embracing Republican economic values. He gutted welfare for the poor. He targeted poor minorities with crushing incarceration policies. He deregulated banking and finance. He promoted global free trade policies that helped consumers by increasing cheap imports, but also helped erode the blue collar middle class as manufacturing moved abroad.

The gap between actual Americans widened. Largely abandoned by their party at the federal level, Liberals looked for allies in local politics and in intellectual circles. And to combat right wing propaganda, they focused on the cultural institutions and industries in LA and NYC they had connections to. Instead of Rush Limbaugh and the like, they had Hollywood movies and TV shows that subtly reflected their values. Instead of Fox News, they had The Daily Show and its successors. And instead of corporate Country music that pandered to provincialism and Conservative values, they had snide jokes about Fly Over Country.

As the pressure to conform has lessened, many people have self-selected conformity through political partisanship. Perhaps that is ironic. Either way, America’s Post-War/Cold War culture of conformity, which centered around nation, not party, has died. This Trumpist moment represents its final spasmodic flailing, its screeching funeral dirge in the face of impermanence and change. Partisan divisions have grown into a yawning chasm that would have shocked many Americans who survived the Great Depression and World War II.

As the pressure to conform has lessened, many people have self-selected conformity through political partisanship. Perhaps that is ironic. Either way, America’s Post-War/Cold War culture of conformity, which centered around nation, not party, has died. This Trumpist moment represents its final spasmodic flailing, its screeching funeral dirge in the face of impermanence and change. Partisan divisions have grown into a yawning chasm that would have shocked many Americans who survived the Great Depression and World War II.

We should be careful not to celebrate the conformist pressures of the long 1950s. Contemporary social critics frequently mocked conformity, and for good reason. The pressure to conform encouraged anti-intellectualism, patriarchy, racism, homophobia, and many other forms of repression and inequality. And of course, even at the time, conformity was somewhat illusory. Major sources of tension were already evident after WWII (eg. civil rights and the emerging generational divide). And many more were about to erupt. However, for better and for worse, the culture of conformity did, at least somewhat, bind American society together with a few common beliefs.

Of course the decline of conformity and the rise of untrammeled partisanship does not explain how Donald Trump became president. But it does help explain why he could confidently (and probably accurately at this point) boast that many of his supporters would stand by him even if he committed murder in broad daylight; why more than two-thirds of Republican voters think he handled his stunningly disastrous summit with Vladimir Putin “well”; and why loyalists continue to support him even as it becomes more and more apparent that he is not only grossly incompetent and a distinctly horrible human being, but quite possibly even a compromised Russian asset.

That is, how tens of millions of American citizens can participate in democratic politics as if they were nothing more than sports fans blindly rooting for their team no matter what.

Akim Reinhardt’s website is ThePublicProfessor.com