by Joseph Shieber

The traditional assumption in the United States has been that each person is individually responsible for their own health care. In other words, the US has a system in which the wealthy are able to afford more or better care (with the understanding that more care does not always lead to better health outcomes!), and the poor are able to afford less or no care.

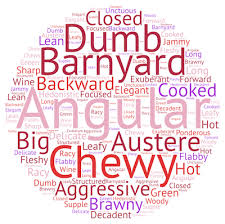

There is something intuitively appealing about the idea that you should be rewarded in relation to the work that you’ve done or the results that you’ve achieved. It’s the basis of the well-known children’s fable, “The Little Red Hen”, in which the hen tries to get her fellow barnyard animals (dog, goose, etc.) to help her sow the seeds, reap the wheat, grind the grain, and bake the bread. Since none of the other animals are willing to help, when the bread is done the hen eats it all herself. In fact, the fable is so intuitively plausible that folksy free-market hero Ronald Reagan — pre-Presidency — used it himself.

The idea behind “The Little Red Hen” is so intuitively appealing that it’s not just limited to free market views. Even socialist thinkers from pre-Marxists like Ricardian socialists to later theorists like Lenin and Trotsky embraced the formula, “To each according to his works”, rather than Marx’s “To each according to his needs”.

Indeed, in a very useful paper, Luc Bovens and Adrien Lutz trace back the dual threads of “to each according to his works” and “to each according to his needs” to the New Testament. So, for example, in Romans 2:6, we see that God “will render to each one according to his works” (compare Matthew 16:27, 1 Corinthians 3:8).

In contrast, in Acts 4:35, we read that “There was not a needy person among them, for as many as were owners of lands or houses sold them and brought the proceeds of what was sold … and it was distributed to each as any had need” (compare Acts 2:45).

The deep textual roots of these two rival maxims suggests that each exerts a strong intuitive pull — though perhaps not equally strong to everyone.

Public health emergencies, however, reveal the fragility inherent in the motto of “to each according to his works” when it comes to health systems. Everyone’s health is interconnected, and that the ability of each individual to fight infection depends in part on everyone else’s having done their part. Read more »

If you, like me, have read premodern philosophers not just for antiquarian interest but also as possible sources of wisdom, you will probably have felt a certain awkwardness. Looking for guidance or assistance in ordering our own beliefs, attitudes and actions, we inevitably run into the problem that the great thinkers of the past knew nothing about what our world would look like.

If you, like me, have read premodern philosophers not just for antiquarian interest but also as possible sources of wisdom, you will probably have felt a certain awkwardness. Looking for guidance or assistance in ordering our own beliefs, attitudes and actions, we inevitably run into the problem that the great thinkers of the past knew nothing about what our world would look like.

Being a horrible person is all the rage these days. This is, after all, the Age of Trump. But blaming him for it is kinda like blaming raccoons for getting into your garbage after you left the lid off your can. You had to spend a week accumulating all that waste, put it into one huge pile, and then leave it outside over night, unguarded and vulnerable. A lot of time and energy went into creating these delectable circumstances, and now raccoons just bein’ raccoons.

Being a horrible person is all the rage these days. This is, after all, the Age of Trump. But blaming him for it is kinda like blaming raccoons for getting into your garbage after you left the lid off your can. You had to spend a week accumulating all that waste, put it into one huge pile, and then leave it outside over night, unguarded and vulnerable. A lot of time and energy went into creating these delectable circumstances, and now raccoons just bein’ raccoons.

Socrates, snub-nosed, wall-eyed, paunchy, squat,

Socrates, snub-nosed, wall-eyed, paunchy, squat,

Over the past week, Pakistan has been consumed by the Aurat (Women’s) March, which was held today, March 8, International Women’s Day, in all the major cities of the country. The march’s aim is to highlight the continued discrimination, inequality, and harassment suffered by women. There are some people against it who argue that the march should not be allowed, but the Islamabad High Court has rejected the petition that asked for its cancellation. So the march happened.

Over the past week, Pakistan has been consumed by the Aurat (Women’s) March, which was held today, March 8, International Women’s Day, in all the major cities of the country. The march’s aim is to highlight the continued discrimination, inequality, and harassment suffered by women. There are some people against it who argue that the march should not be allowed, but the Islamabad High Court has rejected the petition that asked for its cancellation. So the march happened. During a recent visit to Paris, I squeezed through the crowded bookshelves of the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore, a stone’s throw from Notre Dame, whose charred heights sat masked in scaffolding just across the Seine. It has become something of a Parisian tourist hotspot, mostly because of its association with our favorite Modernist expat writers, immortalized and gilded in a cosmopolitan, angsty, and glamorous mystique through the canonization of their works and, some might argue, the award-winning Woody Allen film Midnight in Paris.

During a recent visit to Paris, I squeezed through the crowded bookshelves of the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore, a stone’s throw from Notre Dame, whose charred heights sat masked in scaffolding just across the Seine. It has become something of a Parisian tourist hotspot, mostly because of its association with our favorite Modernist expat writers, immortalized and gilded in a cosmopolitan, angsty, and glamorous mystique through the canonization of their works and, some might argue, the award-winning Woody Allen film Midnight in Paris.

Research by linguists

Research by linguists

There was this one moment. A sunny June day in Nebraska. No one was around. I dribbled the basketball over the warm blacktop, moving towards a modest hoop erected at the end of a Lutheran church parking lot. I picked up my dribble, took two steps, sprung lightly from my left foot, up and forward, my right arm extending as my hand gracefully served the ball to the white backboard. Its upward angle peaked, bounced softly, and descended back through the netless hoop.

There was this one moment. A sunny June day in Nebraska. No one was around. I dribbled the basketball over the warm blacktop, moving towards a modest hoop erected at the end of a Lutheran church parking lot. I picked up my dribble, took two steps, sprung lightly from my left foot, up and forward, my right arm extending as my hand gracefully served the ball to the white backboard. Its upward angle peaked, bounced softly, and descended back through the netless hoop.