by Michael Liss

The other shoe dropped.

Anthony Kennedy’s idiosyncratic role as a Justice of the United State Supreme Court will come to an end a mere week from now. A lot of things are going to change.

Let’s start with the politics. Kennedy’s leaving cinches the conservative revolution (or counter-revolution) for at least a generation. For the first time in living memory, a conservative Supreme Court will be in position to review and bless the acts of a like-minded Congress and President.

This will occur regardless of who is confirmed (Trump’s list is one to which moderates need not apply), but, unless a bolt of lightning strikes, it’s going to be Brett Kavanaugh. Yes, there will be plenty of Kabuki before he gets measured for a new robe, but Kavanaugh is the one who rings every bell for both Republicans and Trump. He’s a Federalist Society member, reliably conservative on all the big issues, not afraid to advance his interpretation of the law even when it conflicts with precedent, and has a past history of partisan politics. His nomination even offers a prize in the Cracker Jack box—the unique, magnificent straddle of having worked aggressively for Ken Starr, but now being deeply committed to the idea that sitting Presidents should be immune from prosecution.

Don’t Democrats have something to say about this? Of course not. Filibusters are dead, following an idiotic series of one-upmanship games between Harry Reid and Mitch McConnell. So, pay no attention to the hand-waving, heavily-accented man from Queens in the donkey suit. Chuck Schumer knows Kavanaugh (or someone just like Kavanaugh) is going to be confirmed, and he knows the confirmation battle is both a risk, and an opportunity, that he has to navigate carefully.

First, Schumer has to let the activists in the Democratic Party vent. There is an unhealed wound from McConnell’s brilliantly evil stonewalling of the Merrick Garland nomination that needs a little more sunlight. Second, he needs to worry about the size of his own caucus in 2019. Everyone knows that there are 10 Democratic Senators up for reelection in states that voted Trump—several of those races are likely to be cliff-hangers at best. If I had to bet, the Democrats will have a net loss of at least three seats, and it could be significantly worse. Third is more existential. Schumer also has to worry about 2020, as a loss there will basically end the two-party system. Several Democratic Senators, including Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris (who is actually on the Judiciary Committee), Kirsten Gillibrand, and, of course, Bernie, are likely to look to use the proceedings as a showcase. That’s fine—there is no particular reason to get in the way of them, if they focus on issues people care about. But the Trump reelection team (including affiliated media) will be thrilled beyond all measure if the main Democratic contenders use the hearings as a rerun of Hillary’s 2016 campaign, which lacked ideas and often devolved into identity politics. No one beats Trump at identity politics.

How does Schumer deal with this stew? By accepting reality (which I suspect he already has). First, do the math. There is no way Lisa Murkowski and Susan Collins will be the votes to kill Kavanaugh’s nomination. We know this because they already are making cooing noises, notwithstanding their expressed concerns about SCOTUS overturning Roe v. Wade. We also know it for another reason. They can do the same math. There are 49 yes votes right now (assuming McCain votes) without them. One more makes 50, and Pence breaks the tie. Neither of them wants to force McCain to come to Washington. And neither wants to take responsibility for killing this nomination—what’s the point when Trump will just follow up with the next Roe opponent? A lot of people look to Murkowski and Collins to be independent/mavericks, but a closer examination of their voting records doesn’t really support that. Rarely do they use the leverage one would assume they have. Both have a few issues where they will break from party orthodoxy, but, almost all of the time, those are “safe” votes—ones that don’t swing the results. McConnell is smart enough to know that, not to press them to take the hard ones except when absolutely necessary, and not to jeopardize their standing at home.

Schumer is just as smart (and remember he’s the guy who, in 2012, recruited many of the now-endangered Democratic Senators from some of those unlikely Red and Purple States). He also knows his New Yawk accent and mug is just as easy a target as Nancy Pelosi’s well-groomed coastal elitist granny look. It’s not going to sell well in places like West Virginia (Joe Manchin), Montana (Jon Tester), North Dakota (Heidi Heitkamp) or Indiana, (Joe Donnelly). That’s actually a plus, because those folks can show their independence and adherence to local values of community, fair play, and moderation by voting for the “qualified” nominee. Schumer is not twisting their arms in a lost cause—rather, he’s privately going to give them the thumbs up to use him as a foil. And they already are. Manchin just said Schumer “can kiss my ____,” and I seriously doubt it didn’t get a secret grin from the Minority Leader.

So, if it’s already over but for the speechifying and play-acting, what does this really mean to most Americans? On many things, practically nothing. The majority of SCOTUS decisions are actually unanimous. Only about a sixth are 5-4 or 5-3. Of course, the close ones have often been the intensely controversial ones—the ones in which we, and activists on both sides, are most interested. So, let’s talk about how swapping out Justice Kennedy for Justice Kavanaugh changes things, with the given that hard-core conservatives are positively swooning with ecstasy at the opportunity.

Three things to keep in mind:

First, Justice Kennedy wasn’t the centrist on the Court, he was the Median. The Median has now moved to Chief Justice Roberts, and he is substantially more conservative than the already conservative Kennedy. But if Kennedy was basically conservative, meaning aligned with Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, and Roberts on all virtually all close votes, which he was, particularly in the Term that just concluded, does it really matter? The short answer…it matters, a lot, and for two major reasons: what I’ll call the Obscure Structural One, and the Practical One.

Let’s start with Obscure. Not every case “goes all the way to the Supreme Court.” Rather, except in the comparatively rare “Original Jurisdiction” matters, SCOTUS chooses what cases to hear by “granting certiorari” to consider appeals from lower court rulings. Granting cert must be done on the votes of four Justices, and, beyond matters that may simply not merit their attention, sometimes the granting of cert is tactical: They don’t want to disturb the lower court rulings on potentially controversial issues because they don’t think the time is ripe to reconsider, or because they have uncertainty as to the result (and therefore don’t want to reaffirm or set a precedent). But if they thought they could convince a fifth (let’s say, our new “Median,” Roberts) they might. Granting cert can be a big deal—it means there is a potential that SCOTUS might make a major, controversial ruling, either making new law, or overturning existing precedent.

Now, the Practical One: The farther the Median moves towards one pole or the other, the broader the potential rulings. If we assume Kennedy was more centrist, then the two ideological sides had to “bid” for his favor—and this coalition-building is far more important than many people realize. The public looks for binary rulings—yes or no—but many Supreme Court decisions reach yes or no in a manner reflecting a preference for “Judicial Restraint”—seeking narrow grounds, and, respecting existing precedent as much as possible. Go too far, and you risk the fifth vote leaving the coalition. This doesn’t stop individual Justices from joining in the Decision and then indulging themselves in a Concurrence (Justice Thomas, for example, has suggested that the Establishment Clause does not apply to the States), but the core ruling of the Court is a function of the maximum the deciding vote(s) can accept. If Roberts is the new Median, and Roberts is more conservative than Kennedy, those 5-4 votes will now tend to be more conservative, in the sense that they will go further because the extremely conservative Justices will have to “give” less to Roberts.

This is a problem, and more than just for centrists and liberals. An unrestrained Court can be a dangerous one, both to the country and to its own legitimacy. This is particularly true when it indulges a preference for self-defined truths as a justification for significantly exceeding what the public wants. The more liberal Warren Court lost some of the public’s confidence with a string of criminal procedure cases. The Roberts Court may do the same, if, to use the Chief Justice’s analogy about being an umpire, it seems to make the call even before the ball is out of the pitcher’s hand.

As we move ever-harder Right, on the business/labor balance, on regulation, on voting rights and fair representation, on Executive Power, we are also coming to realize that true limited government conservatives barely exist anymore. They have been replaced by opportunistic conservatives who have no problem using the power of the State situationally to achieve political ends. SCOTUS, even if it were motivated that way, can’t do that on its own—SCOTUS doesn’t enact or execute laws, rather, it sets the ground rules for what can be enacted or executed. But, when what is left of the astringent, selective variant of limited-government judicial conservatism comes together with opportunistic political conservatism, you can get a maximalist result—one that can vastly outstrip where the public is or wants to go. So it will be with reproductive rights and, to an as-yet-undetermined extent, privacy rights, as well.

We don’t need a lot of granular legal analysis when SCOTUS decides to take down Roe v. Wade. The new majority clearly opposes reproductive rights, even as a substantial majority of the public supports access to abortion. But SCOTUS gets to make the rules, so Roe v. Wade is as good as gone. It won’t happen immediately—Justice Thomas will not go running out into the street on the First Monday in October looking for church bells to ring, but, after the process—a ripe case, the granting of cert, briefing and oral arguments, and then a decision, Roe will end, probably by June 2019.

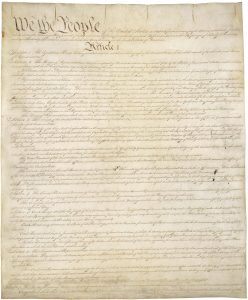

This is as much a certainty as Trump tweeting in the early morning hours. What we don’t know is what logic the Opinion will adopt and how far it will go. Roe doesn’t exist without the Court’s recognition of a right of privacy emanating from a “penumbra” of enumerated (as in, “written down in the Constitution”) rights (Griswold v. Connecticut, an earlier contraception case, laid the groundwork). But a generalized right of privacy, the type that seems intuitive to most Americans, is anathema to many “Originalists” precisely for that reason—it may be intuitive, but that’s all it is. I suspect that at least two of the Justices, if given a blank slate, would happily discard most or all privacy rights, and one or two more might significantly limit their application. Is there a fifth (Roberts) to take a wrecking ball to the entire concept?

I am going to assume (and hope) not yet, and SCOTUS will limit itself to a surgical strike on abortion. What are the practical implications? After all, overturning Roe does not bar the procedure, it merely eliminates the Constitutional restraints on individual States in their ability to regulate, restrict, and criminalize abortions. Superficially, that sounds somewhat calming—a Tenth Amendment solution where the Bible Belt and uber-conservative states do their thing, and the rest of the country goes its own way.

Ah, not so fast. According to the Guttmacher Institute, 45 states have some restrictions on their books. Ten have what we could call legacy bans—statutes that predate the original Roe decision and were never formally repealed. Here are the 10: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Mississippi, Oklahoma and West Virginia—all good conservative states where no one ever wants or needs an abortion—and (brace yourself) Massachusetts, Michigan, New Mexico, and Wisconsin. What’s the over-under on ambitious Attorney Generals and local District Attorneys who will be looking to make a name for themselves by trying to enforce laws that the general public didn’t even know existed?

If the last 18 months have shown anything, it’s just how effective Republicans have been in exercising strict and sweeping one-party government, even with narrow majorities. Does anyone doubt that, once the Supreme Court rules that reproductive rights no longer exist, Paul Ryan’s successor (assuming the GOP retains the House) and Mitch McConnell will quickly roll out federally preemptive legislation with severe limitations or even a nationwide ban? Any doubts that the pressure on moderate Republicans would be intense to take one for the team, even at the potential cost of their seats? Any doubts our deeply religious President would sign it, if it could make its way through Congress, and direct Jeff Sessions to do whatever it took to enforce it before enactment?

In a painful and even perverse way, the post-Roe-repeal trench warfare may actually do some good. It will bring focus to the bigger question: What other liberties will draw the unfriendly attention of “limited government” conservatives as they look to terraform a nation more to their liking?

The next battle about rights is perhaps the ultimate one: Who really owns your life? What should be subject to unbridled scrutiny and regulation, and what should really be private, yours to keep or voluntarily cede, as you choose, to be invaded only under very limited circumstances?

Let me end with one deeply conservative idea: the more power the government has to regulate your life and the lives of your fellow citizens—even if you agree with a particular application of that power—the less liberty, you, as an individual, retain.

That is why you should always vote as if your rights depended on it Because they will.