by Mindy Clegg

The taste for the end times as a dramatic backdrop well preceded our current pandemic lock-down, but now seems as good a time as any to explore the popularity of end-of-time dramas as any other. Perhaps we can take some solace from a discussion of others surviving worse situations than our own, even if fictional. Philosopher and pop culture theorist Slavoj Žižek (or it might have been Fredrick Jameson) once noted that the popularity of apocalyptic culture tended to be driven by the all-encompassing power of our current global system, noting that it’s easier for us to imagine the world’s end rather than it’s transformation.1 This seems to break with earlier popular culture that imagined some level of continuity between our present and the future, such as Star Trek. If today we have a harder time imagining productive change to our globalized system, at least our visions of its collapse are numerous and offer compelling viewing. The Walking Dead comic and TV series are a prime example of that sort of entertainment. I argue here that although the series and comic seem on the surface to explore only the collapse of our modern systems of governance and our globalized economy, the focus instead rests on what we keep and what we leave behind as we rebuild in the wake of some kind of wide-spread devastation. In many ways, the Walking Dead offers an alternative to ideologies like the Milton Friedman “shock doctrine” that turns disasters into fodder for privatization.2

Just a note for fans of the show or comic: I’ll include spoilers here for what I’ve watched thus far and for the comic, as that has recently concluded. Read more »

I’m sitting in front of my window on the world sipping a disappointing Cabernet Sauvignon from Napa Valley and thinking about travel plans for next summer and fall. I’m proceeding as if everything were normal knowing full well they won’t be, especially not with our “leadership”. Every time I try to write something insightful about wine, these lyrics from the bard of Duluth run through my mind:

I’m sitting in front of my window on the world sipping a disappointing Cabernet Sauvignon from Napa Valley and thinking about travel plans for next summer and fall. I’m proceeding as if everything were normal knowing full well they won’t be, especially not with our “leadership”. Every time I try to write something insightful about wine, these lyrics from the bard of Duluth run through my mind: Quarantined, sheltered, holed-up, bunkered, hiding, homebound, trapped–whatever you want to call it–I am, probably (hopefully) like you, socially isolated from everyone but my family, trying to do my part in “flattening the curve” on a virus that seems intent on overwhelming a system ill-equipped to deal with such a thing. Like the prisoner who resorts to counting the pockmarks on the cement wall of his cell to pass the time, I have used some of my new, spare time to take an account of my collection of shoes and boots. But unlike Derrida or Heidegger in regards to Vincent Van Gogh’s famous painting of boots, I have absolutely no desire to be profound or provocative. I simply and admittedly have a bit of a shoe and boot “problem” that I would like to discuss; not sneakers or trainers—never caught the bug—but handcrafted leather footwear that typically go from very expensive to “holy crap that’s a lot of money for boots!” My wife doesn’t understand it. “Another pair of boots?” she sneers as I unapologetically remove my latest purchase from its sturdy cardboard case; a stunning pair of Horween shell cordovan lace wing-tip boots, color number 8, with Goodyear welts, lug soles and copper rivets, handmade in the USA by one of the oldest family-owned shoe/boot-makers in the country. They ain’t cheap but they’re not “holy crap” expensive either. They are beautiful and rough, sophisticated and classic, yet in no way arrogant or pretentious and will be around, if properly cared for, long after I am dead. Seems like a deal to me.

Quarantined, sheltered, holed-up, bunkered, hiding, homebound, trapped–whatever you want to call it–I am, probably (hopefully) like you, socially isolated from everyone but my family, trying to do my part in “flattening the curve” on a virus that seems intent on overwhelming a system ill-equipped to deal with such a thing. Like the prisoner who resorts to counting the pockmarks on the cement wall of his cell to pass the time, I have used some of my new, spare time to take an account of my collection of shoes and boots. But unlike Derrida or Heidegger in regards to Vincent Van Gogh’s famous painting of boots, I have absolutely no desire to be profound or provocative. I simply and admittedly have a bit of a shoe and boot “problem” that I would like to discuss; not sneakers or trainers—never caught the bug—but handcrafted leather footwear that typically go from very expensive to “holy crap that’s a lot of money for boots!” My wife doesn’t understand it. “Another pair of boots?” she sneers as I unapologetically remove my latest purchase from its sturdy cardboard case; a stunning pair of Horween shell cordovan lace wing-tip boots, color number 8, with Goodyear welts, lug soles and copper rivets, handmade in the USA by one of the oldest family-owned shoe/boot-makers in the country. They ain’t cheap but they’re not “holy crap” expensive either. They are beautiful and rough, sophisticated and classic, yet in no way arrogant or pretentious and will be around, if properly cared for, long after I am dead. Seems like a deal to me. Some years ago, a friend told me about his dilettantish taste for nicotine, indulgence in which, however, he noted ruefully, was often thwarted by his young daughter. He supposed the vehemence of her protests derived, simply, from a concern for his health – to which I responded, perhaps: but that there might also be a further factor. His daughter, I reminded him, was just barely prepubescent, and thus newly arrived in what classical psychoanalysts call the “latency phase”, in which the para-erotic pulsions characterizing the various stages of her psychosexual development to date, and directed at her opposite-sex parent, the putative object of her nascent desire, are in retreat under the dawning realization that she is unlikely to be successful in her Oedipal struggle; and so she begins instead to bend to the will of a superego offering a compensatory identification with her triumphant rival, her mother. (This was before I had read Didier Eribon.) As a consequence, I concluded, his daughter was in the midst of developing prohibitive feelings of disgust at the merest suggestion of the desire she was busy repressing, and was thus likely to react with exaggerated horror at any sign of eroticism on the part of her erstwhile object.

Some years ago, a friend told me about his dilettantish taste for nicotine, indulgence in which, however, he noted ruefully, was often thwarted by his young daughter. He supposed the vehemence of her protests derived, simply, from a concern for his health – to which I responded, perhaps: but that there might also be a further factor. His daughter, I reminded him, was just barely prepubescent, and thus newly arrived in what classical psychoanalysts call the “latency phase”, in which the para-erotic pulsions characterizing the various stages of her psychosexual development to date, and directed at her opposite-sex parent, the putative object of her nascent desire, are in retreat under the dawning realization that she is unlikely to be successful in her Oedipal struggle; and so she begins instead to bend to the will of a superego offering a compensatory identification with her triumphant rival, her mother. (This was before I had read Didier Eribon.) As a consequence, I concluded, his daughter was in the midst of developing prohibitive feelings of disgust at the merest suggestion of the desire she was busy repressing, and was thus likely to react with exaggerated horror at any sign of eroticism on the part of her erstwhile object. I am one of those people who cannot sit still. I wasn’t good at it as a child, and as the decades pass, every indication is that I will never be good at it. I suspect I inherited this from my father, who lacked a single iota of Sitzfleisch, and have passed on the gene to one of my children (no need to name names here, she knows who she is and who to blame.)

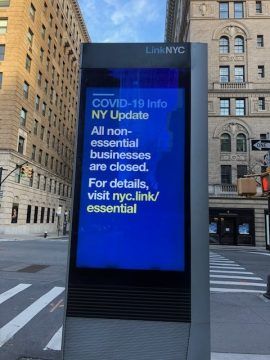

I am one of those people who cannot sit still. I wasn’t good at it as a child, and as the decades pass, every indication is that I will never be good at it. I suspect I inherited this from my father, who lacked a single iota of Sitzfleisch, and have passed on the gene to one of my children (no need to name names here, she knows who she is and who to blame.) Of course, this was all before Coronavirus, all before I was deemed “non-essential” and even officially old. I’m not sure where this “old” nonsense came from, but the solicitude for my health and wellbeing merely as a function of an arbitrary number is a little hard to take. All of a sudden there seem to be an awful lot of things I’m not supposed to be doing. I never thought “aging in place” was meant to be taken literally.

Of course, this was all before Coronavirus, all before I was deemed “non-essential” and even officially old. I’m not sure where this “old” nonsense came from, but the solicitude for my health and wellbeing merely as a function of an arbitrary number is a little hard to take. All of a sudden there seem to be an awful lot of things I’m not supposed to be doing. I never thought “aging in place” was meant to be taken literally.

Two minutes after the explosion the fire station alarm rang. The firefighters who scrambled from sleep to the scene, along with the regular overnight shift at reactor four, were among the first fatally irradiated. Unquestioned heroes, they battled the blazes until dawn with no special training for a nuclear accident, in shirtsleeves, using only conventional firefighting methods. They walked amid flaming, radioactive graphite.

Two minutes after the explosion the fire station alarm rang. The firefighters who scrambled from sleep to the scene, along with the regular overnight shift at reactor four, were among the first fatally irradiated. Unquestioned heroes, they battled the blazes until dawn with no special training for a nuclear accident, in shirtsleeves, using only conventional firefighting methods. They walked amid flaming, radioactive graphite.  by Holly A. Case (Interviewer) and Tom J. W. Case (Hermit)

by Holly A. Case (Interviewer) and Tom J. W. Case (Hermit)

I’ve been telecommuting on and off for over 17 years. I first started working from home because I’d moved 150 miles away from the company I’d been contracting for over the previous 4 years. Back then, I worked in a small team that was part of a larger team in a huge corporation. My immediate boss was very supportive of my new working arrangement, but he had a peer, who even though she had no responsibility for my work, felt the need to have her say to their mutual boss. Her thoughts went along lines of, “how do we know she’s really working when she never comes into the office?”, to which my boss said, “well someone is getting all the work done, so if it isn’t Sarah, who is it?”. This conversation seems almost quaint nowadays, when even before the current pandemic, a decent amount of the white-collar professional workforce worked at least occasionally from home. And now of course, we’ve all been thrust into a great social experiment to see just how productive, perhaps more rather than less even, the entire workforce will be working remotely. Everyone else is now catching up to what I’ve known for a long time: it’s pretty nice to not have to deal with the daily commute and that time can really be used more productively than fighting for space on mass transit; you have to be at least somewhat disciplined to make sure you only go so many days working in the same pjs you’ve been in all week; working from home can give you a lot of time to multitask life stuff like unloading the dishwasher while you’re listening to a conference call, but it can also be harder to draw boundaries between home and work life, and this takes some practice.

I’ve been telecommuting on and off for over 17 years. I first started working from home because I’d moved 150 miles away from the company I’d been contracting for over the previous 4 years. Back then, I worked in a small team that was part of a larger team in a huge corporation. My immediate boss was very supportive of my new working arrangement, but he had a peer, who even though she had no responsibility for my work, felt the need to have her say to their mutual boss. Her thoughts went along lines of, “how do we know she’s really working when she never comes into the office?”, to which my boss said, “well someone is getting all the work done, so if it isn’t Sarah, who is it?”. This conversation seems almost quaint nowadays, when even before the current pandemic, a decent amount of the white-collar professional workforce worked at least occasionally from home. And now of course, we’ve all been thrust into a great social experiment to see just how productive, perhaps more rather than less even, the entire workforce will be working remotely. Everyone else is now catching up to what I’ve known for a long time: it’s pretty nice to not have to deal with the daily commute and that time can really be used more productively than fighting for space on mass transit; you have to be at least somewhat disciplined to make sure you only go so many days working in the same pjs you’ve been in all week; working from home can give you a lot of time to multitask life stuff like unloading the dishwasher while you’re listening to a conference call, but it can also be harder to draw boundaries between home and work life, and this takes some practice.

I had planned to do another philosophy post this month, but I can hardly concentrate on such things about now and I bet you can’t either. Instead I’ve been hanging out on Bandcamp and

I had planned to do another philosophy post this month, but I can hardly concentrate on such things about now and I bet you can’t either. Instead I’ve been hanging out on Bandcamp and

Manhattan always has been and always will be New York City’s geographic and economic center. But if you’re actually from New York, then you’re very likely not from Manhattan. Like me, you’re from one of the outer boroughs: The Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, or Staten Island. And as far as we’re concerned, we’re the real New Yorkers. The natives with roots and connections, and the immigrants who are life-and-death dedicated to making them, not the tourists who come for a weekend or a dozen years before trundling back to America.

Manhattan always has been and always will be New York City’s geographic and economic center. But if you’re actually from New York, then you’re very likely not from Manhattan. Like me, you’re from one of the outer boroughs: The Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, or Staten Island. And as far as we’re concerned, we’re the real New Yorkers. The natives with roots and connections, and the immigrants who are life-and-death dedicated to making them, not the tourists who come for a weekend or a dozen years before trundling back to America.

Kazuo Shiraga. Untitled 1964.

Kazuo Shiraga. Untitled 1964. There has been much discussion lately of whether the COVID-19 pandemic will spell the end of globalization. It’s hard to get economists to agree on the meaning of the numbers, or foreign policy analysts to commit to a vision of the future in a world that changes from one moment to the next. Globalization means different things to different people and entities. Its many facets, and many narratives about those facets, complicate discussion about either a contraction or a resurgence of globalization. For corporations, it means access to inexpensive labor markets; for money managers, it means access to capital markets. For the typical business traveler, it may mean something as basic as greater choice of airlines and flight times for an international trip. For an optimistic humanist, it might symbolize enhanced international cooperation and a suppression of nationalism and xenophobia. For an environmentalist, it is marred by the dangerous policies that accelerate climate change. For a technocrat, it seems the obvious economic approach to accompany the paradigm of social-media-fueled connectedness, data collection, surveillance, and targeted marketing.

There has been much discussion lately of whether the COVID-19 pandemic will spell the end of globalization. It’s hard to get economists to agree on the meaning of the numbers, or foreign policy analysts to commit to a vision of the future in a world that changes from one moment to the next. Globalization means different things to different people and entities. Its many facets, and many narratives about those facets, complicate discussion about either a contraction or a resurgence of globalization. For corporations, it means access to inexpensive labor markets; for money managers, it means access to capital markets. For the typical business traveler, it may mean something as basic as greater choice of airlines and flight times for an international trip. For an optimistic humanist, it might symbolize enhanced international cooperation and a suppression of nationalism and xenophobia. For an environmentalist, it is marred by the dangerous policies that accelerate climate change. For a technocrat, it seems the obvious economic approach to accompany the paradigm of social-media-fueled connectedness, data collection, surveillance, and targeted marketing.