by Holly A. Case (Interviewer) and Tom J. W. Case (Hermit)

by Holly A. Case (Interviewer) and Tom J. W. Case (Hermit)

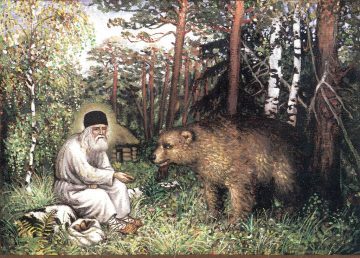

The following is the continuation of an interview with Tom, a pilot who has largely withdrawn to a small piece of land in rural South Dakota. Parts I and II can be found here and here.

Interviewer: I’d like to ask how you would tell the story of your inner jukebox—perhaps under the title “The Inner Jukebox: A Bildungsroman.”

Hermit: Ah, the inner jukebox, its bearings rusty and contacts dusty. That thing used to roll on an endless reel, telling me and shaping how I feel.

Music, I really used to think, is one of mankind’s greatest achievements. Now I just think less, it seems, or about different things. But even as I give music less thought, it surely is very special.

Music can fit a mood, bend or even break a mood, make a new mood, take you places—what a thing! But at the same time, there is always the chance of going missing as in other ways I have described. In no way have I shunned or avoided music, but I do not seek its warp-voyager quality any longer. I must say that I am not beyond being grabbed and taken for a ride from time to time, however.

The soundtrack you mentioned, I used to make so many playlists to fit time, place, and mood, and it never failed that by the time I had finished making the perfect playlist, it no longer fit those things. I might conclude that it has everything to do with the aforementioned coloring; that the more one truly accepts their immediate surrounding and circumstance, there might just not be a track cued up (unless on an elevator, help us).

All of that said, it can be counted on that I am nearly always narrating my plodding with ditties and tunes spontaneously coined.

Interviewer: On the subject of where the mind goes (and warp-voyagers), what are the thought patterns that recur in hermitude?

Hermit: This is perhaps the one area in which I struggle the most. Thought.

I said just before that I think less, or about other things now. Not true, that, upon reflection. I interact with my thoughts less, but there is no evidence that I think less. Thank you for reminding me.

Rabbit holes. Down and down them I would go, sometimes unwittingly, sometimes because something interesting popped up seeming worthy of a closer look, but never did I feel like I had much control. I tried to control my thoughts, really tried, but never could. So it seems the thought best suited to my hermitude is the one reminding me not to use my thoughts as a platform to stand on, but to witness them as an ever changing flow which I cohabitate with but do not possess, and to grant them only as much control over my actions as they give me over theirs.

Along those lines, it might be impossible to say which ones benefit or harm the cause of hermitude, but thoughts of caution around the idea of inadvertent color application by other thoughts seems warranted (see “Ask a Hermit, Part II”). Also, any thought in a moment of crisis, I would argue, is better acted upon—unless or until a better one comes along—than simply observed as a mere thought.

Interviewer: What happens to language in a state of hermitude? Is it heard/spoken/felt differently? Do you start to understand or notice other ones that you maybe didn’t understand before (or didn’t know existed)?

Hermit: I have a difficult time anymore viewing language as anything other than the perfect, proverbial double-edged sword; one edge honed for slicing precisely in the best and most beneficial of ways, the other honed for slicing precisely in the worst and most destructive of ways; the single most beautiful and menacing tool ever devised. The trouble is that the two edges seem indistinguishable from one another, the whole piece crafted with such care that it cannot help but be as dangerous as it is useful, even hopeful.

Despite the seemingly equal ratio of attributes, the responsibility of knowing and choosing which edge to project ultimately falls on the wielder. So much faith must be given this wielder, and by them, for directly across is the port of the sword’s intention, responsible in turn for receiving or turning away what is incoming.

What I am really trying to say is this: There are so many variables to both the application and receipt of language, that I am not at all certain it can be trusted—least of all my own applications and receptions of it. And so I use less language in general now, this interview being quite the exception. In fact, such is a key aspect of my own hemitudinal process and, until I can better understand what is truly afoot as I swing away, it will continue to be. Given the same collection of notes as someone else, they might make a symphony of them, I might make a train horn.

(Have I said too much?)

Now, to perhaps answer your question (or to further present the incorrect edge), as I vocalize and think less with words, I have decidedly come to an elevated level of communication with my immediate surroundings. With the dogs I have come to “hear” things, unspoken, in myriad new ways. (The dogs are exceptional communicators, not just by what they say in not saying anything, but in the way they might have arrived at not saying it. Fascinating. All one has to do is not listen.) The use of eyes has taken the place of many noises—”ocular requeggestions,” I call them, and they go both ways—vocalization used mostly for distant praise, attention getting, or situations not conducive to eye contact anymore. The same in some ways with rabbits, noise just freaks them out, eyes seem to soothe them, or hypnotize them… There is no cracking the chicken code for me, though I know a few words. As for the wilder things, nature, let us say, it seems incapable of even being heard until one stops completely—even one’s own breathing can mask its messages—and takes the time—sometimes a lot of time—to hear it. What happens then is profound. I might like to find the same things true amongst us all.

If you have a question for Tom, you can send it to [email protected] (subject heading: Ask a Hermit).