Stuck has been a weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday since November. The table of contents with links to previous chapters is here.

by Akim Reinhardt

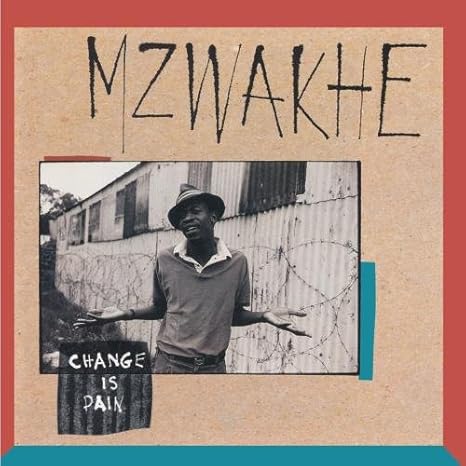

“Change is pain.” —South African poet Mzwakhe Mbuli

Manhattan always has been and always will be New York City’s geographic and economic center. But if you’re actually from New York, then you’re very likely not from Manhattan. Like me, you’re from one of the outer boroughs: The Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, or Staten Island. And as far as we’re concerned, we’re the real New Yorkers. The natives with roots and connections, and the immigrants who are life-and-death dedicated to making them, not the tourists who come for a weekend or a dozen years before trundling back to America.

Manhattan always has been and always will be New York City’s geographic and economic center. But if you’re actually from New York, then you’re very likely not from Manhattan. Like me, you’re from one of the outer boroughs: The Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, or Staten Island. And as far as we’re concerned, we’re the real New Yorkers. The natives with roots and connections, and the immigrants who are life-and-death dedicated to making them, not the tourists who come for a weekend or a dozen years before trundling back to America.

Manhattan below 125th Street (in the old days below 110th) is a playground for the wealthy, a postcard for tourists to visit. For the rest of us, it’s a job, it’s that place you have to take the subway to. Maybe that sounds like people from the outer boroughs have a chip on their shoulders. Trust me. They don’t. By and large, they’re very confident in their identity. They know exactly who they are. They’re New Yorkers. And you’re not.

However, between the boroughs themselves there can be a bit of a rivalry, and Manhattan’s not really part of that, because Manhattan is just its own thing, leaving the other four that jostle and jockey for New York street cred. For example, hip hop was practically born from tussles between the Bronx and Queens. But generally, it’s really not much of a contest. As a Bronx native, much to my chagrin, Brooklyn usually wins. Or at least, it used to.

The Bronx doesn’t have a lot to hang its hat on, but the things we have are big. The Yankees are the most successful sports franchise in world history. We have a big zoo, if you’re into that kinda thing. We created a pretty cool cheer. And of course we (that’s the proverbial “we,” not me in anyway) literally invented rap, later to be called hip hop, the world’s dominant musical and fashion force for at least a quarter-century now. But when I was a kid, it just didn’t seem to matter. Brooklyn still had a strut that the other boroughs could not match.

Growing up in the Bronx during the 1970 – 80s, Brooklyn was formidable. It dominated the city in ways that the other outer boroughs, and in some ways even shiny little Manhattan itself, never could. Its power stemmed from its moxie and its enormity. An independent city until 1898, millions of people were packed into a dense thicket of poor, working, and middle class neighborhoods. The other boroughs simply could not compete with its muscle and magnitude.

Staten Island is small and remote. It has less than 5% of the city’s population and is the only borough without a subway. Or a bridge connecting it to Manhattan. Honestly, it’s practically New Jersey. The Bronx by itself would be the United States’ 6th largest city, after Philadelphia and before Phoenix, but it’s barely half the size of Brooklyn. And as the only patch of New York City on the North American mainland, it’s poorly positioned to take center stage. Queens is centrally located, has nearly two million people, and is by far the biggest borough by square mileage, nearly five times the size of Manhattan and twice Brooklyn. But that vast space dissipates its identity. No one’s from Queens. They’re all from this or that little neighborhood.

Brooklynites are quick to let you know they’re from Brooklyn. Brooklyn is also right there, just across the East River from lower Manhattan and, frankly, they’re pretty unimpressed by it. Manhattan’s skyline towers over Brooklyn, but Brooklynites are unmoved. For them, it’s just a nice view, as if Manhattan did it all for them. Sure, they go to Manhattan far more often than Manhattanites go to Brooklyn. But the most famous bridge in the world is called the Brooklyn Bridge, as if they own that shit. And it’s still free to cross, because don’t even think about it!

During the 20th century, Brooklyn had a way of stepping up and insisting on representing the rest of us. Nobody outside New York knew shit about Queens or Staten Island. And the Bronx was just something most Americans were scared of, cause boy do white people love being scared of darker skinned people. So it was Brooklyn, in fiction and memoirs, on TV and in movies, in festivals and folklore, that became the face of us, presented as the lifeblood of the city and the home of regular old New Yorkers.

And now? Now Brooklyn’s overrun with trust fund babies from across America who grew up to be NYU students, pampered artists, pseudo-intellectuals, momzillas, and master cheese/gin/sausage/quilt makers. The excesses of its hipster gentrification are comical. I mean, you don’t wish the zombie apocalypse on anyone, but deep down you know that if it erupted there, in the land of artisanal beard oil and luxury lofts, the results would be downright hilarious.

I’ve spent a fair amount of time visiting friends in Brooklyn over the years, but never lived there myself. I don’t have any skin in that game. Even still, I’m disgusted by the hoards of boring, navel gazing rich kids and invasive little starter families. Yes, of course less crime and more money are good. But when I go back home to the Bronx, it’s pretty much still the Bronx. Each time I visit Brooklyn, it seems more and more like a glittery cesspool of monied self-indulgence; kinda like a poor man’s Manhattan. Of course “poor” is supremely relative in that context. Either way, however, being the poor man’s Manhattan is utterly pointless, because the place is NEVER EVER gonna be Manhattan.

The upshot? Brooklyn doesn’t represent outer borough New York anymore. Instead, it’s a model for unimaginative urban planners and money-horny real estate developers in towns and cities across America who dream about turning working class neighborhoods and old downtowns into yuppie playgrounds. You wanna make sure I never move to your section of whatever town or city you live in? Just get your realtors to spout pandering clichés like “This place is the next Brooklyn!” That’s like telling me indigestion is the new gout.

But of course there was never a golden era, either in Brooklyn or anywhere else. As a historian, I can guarantee you that. There really was more crime and poverty in the ‘70s and ‘80s, and of course even more racism and sexism than we still have now. So the changes, as distasteful as I find them on an aesthetic, and even spiritual level, certainly could’ve been a lot worse, because in some ways the old glory days themselves were a lot worse. And at least the place didn’t just become more suburbia. So it’s important to remind myself that despite all of the ways in which it is frustrating, cartoonish, and even pathetic, some very nice things have emerged from changing Brooklyn. Daptone Records is one of those things.

It began with the Dap-Kings, a revivalist soul/R&B/funk outfit. In 2002, they started backing the late, great Sharon Jones. Daptone Records emerged around the band, recording dozens of albums from a stable of in-house and guest artists. In 2007, Amy Winehouse recorded her massive Back to Black album at Daptone, and the Dap-Kings played on her worldwide tour.

It began with the Dap-Kings, a revivalist soul/R&B/funk outfit. In 2002, they started backing the late, great Sharon Jones. Daptone Records emerged around the band, recording dozens of albums from a stable of in-house and guest artists. In 2007, Amy Winehouse recorded her massive Back to Black album at Daptone, and the Dap-Kings played on her worldwide tour.

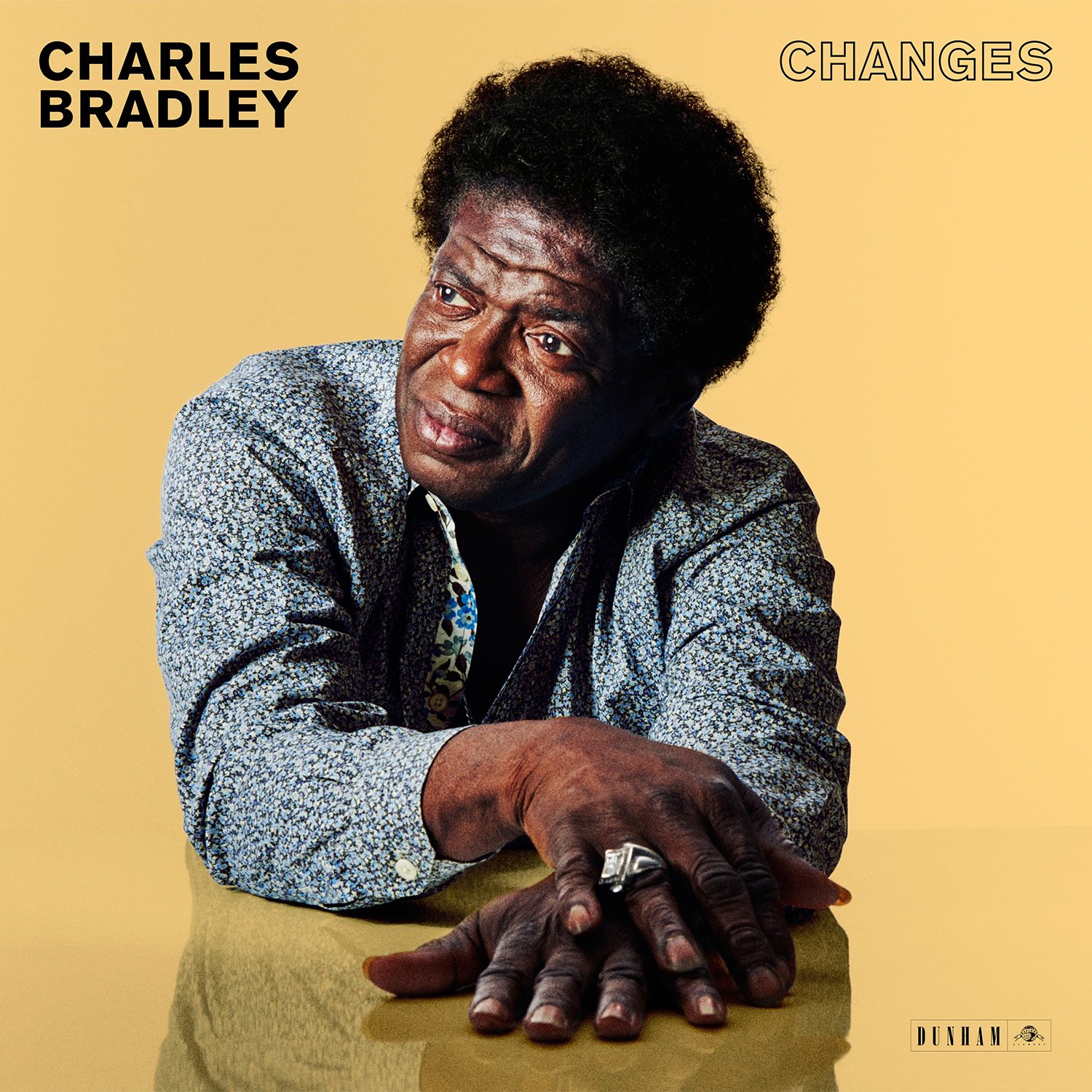

One artist who, like Sharon Jones, found a much overdue career revival on Daptone, was Charles Bradley. The Gainesville, Florida native was 8 years old when he moved to Brooklyn in 1956 with his mother. He ran away at age 14 and and was homeless for two years. He eventually found his way to Maine, where he worked as a chef for ten years and began singing publicly. He then hitchhiked across the North, living in upstate New York, Canada, and Alaska before landing in California in 1977, still shy of his 30th birthday. He spent the next two decades working odd jobs and performing small gigs, usually as a James Brown cover act under various names, including The Screaming Eagle of Soul and Black Velvet. In 1994, he finally returned to Brooklyn, on the eve of its gentrification.

As Brooklyn’s pot began to swirl, Bradley found a home on Daptone Records. Between 2011 – 16, he record three albums for the label. The title track of his final record was a cover of Black Sabbath’s “Changes.” And boy, did he change it.

In 1972, while Bradley was still serving up meals in Maine, heavy metal pioneers Black Sabbath were trying something new. The English group was Birmingham hard. Their first three albums, issued between 1970 – 71, all featured guitarist Tomy Iommi’s jackhammer riffs and wailing solos, Geezer Butler’s (bass) and Bill Ward’s (drums) pounding rhythm section, and Ozzy Osbourne’s manic, unhinged lyrics.

Then they moved to L.A.

The foursome rented a Bel Air mansion owned by a DuPont family scion. It was there that the chaos began overrunning them. While working on their fourth album (titled Vol. 4), they spent about half their budget on cocaine. They wanted to make the song “Snow Blind” their title track, but the record company bucked at naming the album for such an obvious drug reference. Butler later pointed to their time in the mansion as the moment when drinking and drugging stopped being fun.

Ward nearly died when, as a prank, his band mates covered him in gold spray paint from head to toe while he was passed out drunk. He avoided heat stroke, but feared he was about to get fired from the band as his alcoholism grew worse and his attitude and playing deteriorated. His marriage was also crumbling. It seemed all bets were off.

Iommi sat down at a piano and taught himself how to play. He cobbled together some broken chords on the white keys. Osbourne hummed a melody over it. Butler penned lyrics inspired by Ward’s marital woes. The result was the head bangers’ first ever ballad, “Changes.”

It sucks shit. At least that’s my humble opinion. A really god awful song that I can’t make it through if I have access to a Stop button. I guess it stands to reason. One guy writing music on an instrument he doesn’t know how to play; another writing vague lyrics about someone else’s emotional pain instead of his own; and all of them drug-stumbling through a new style of music for the first time.

Of course there are many who disagree with me. The song has countless admirers. In 2003, Osbourne, at the height of his reality TV show fame, recorded a nauseatingly awful duet version with his daughter Kelly. It shot to the top of the UK charts. Later that year, American DJ Felix da Housecat scored a club hit with by remixing “Changes,” almost completely masking the original song with dance beats. Good for him.

In between, several other bands found the song worthy of covering. The Cardigans, Fudge Tunnel, and Overkill each gave it a spin, changing “Changes” to suit their respective styles: Americana folk, noise rock/metal, and thrash.

If the original or any of those cover versions had possessed me, the consequences could have been dire. I don’t’ know if I coulda made it through. And motherfucker, the song did find me. But I lucked out.

I often can’t identify how or when a song gloms onto me. This time, however, it was clear. My girlfriend and I were binging the Netflix animated comedy Big Mouth. The show brilliantly and hilariously chronicles the hormonal whirlpool engulfing a cohort of middle school girls and boys. It’s opening theme song is “Changes.”

But praised be the unknown gods of distant dreams. Big Mouth doesn’t use the horrific original, or the saccharine mommy-daddy remake, or a feline dance mix, or a cover by some band with a bad anal sex pun for a name. Rather, the show opens with an out take of the title cut from Bradley’s final Daptone album. This is a radically different version of “Changes.”

The 3/4 tempo remains the same, but instead of a lethargic waltz, it’s now a tense soul number. Horns swoop in, carrying the song to new heights. And Bradley’s soaring, aching vocals are soaked in a raw, emotional depth that some coked up twenty-somethings in a Bel Air mansion could never evoke, even if it was their changes on paper.

Mzwakhe Mbuli was right. Change is pain. At least for someone. The animated junior high schoolers befuddled by puberty. The drummer caught up in drug addiction and a failing marriage. The comfortable middle aged man pining for a bygone city of modest neighborhoods and unassuming mom and pop shops. The fourteen year old who flees an abusive mother only to become a homeless runaway.

But change, so ceaseless and ineluctable, can also be good. Those junior high schoolers will eventually discover the joys of sex and adulthood. The drummer can live the rest of his life off the iconic music made as a young man. The comfortable middle aged man can live in a different city that he comes to love. And the fourteen year old runaway can one day unleash his pain into a microphone and move the world.

Change can be new beginnings, fresh starts, improved options, and lessons learned. It can be redemption. It can be righteous. It can be a song that’s no longer stuck in your head.

Change can be new beginnings, fresh starts, improved options, and lessons learned. It can be redemption. It can be righteous. It can be a song that’s no longer stuck in your head.

And although change is almost always pain for someone, as difficult as it may be, that pain is often necessary, as Mzwakhe Mbuli also knew, writing and reciting poetry in protest of South African apartheid. For in the end, change is the end.

Charles Bradley died of stomach cancer a month before his rendition of “Changes” possessed me.

Epilogue: Ghost Tracks (2018)

It’s been a year. Nothing.

Well, not exactly nothing. A near constant flow of various songs in and out of my head. But nothing has gotten truly stuck. Nothing has washed over me for weeks. A couple of days at the most, and then onto some fresh tunes. Most days have been a rotation of various song fragments. It’s been a long time since I was possessed.

Long gaps aren’t unheard of. The Table of Contents reveals that I went half a year between the Grateful Dead’s “Touch of Grey” (July, 2015) and Motörhead’s “Ace of Spades” (January, 2016). But this is more than twice as long. I’m not entirely sure what to make of it.

It’s tempting to think that earnestly taking on the project has born fruit. To pat myself on the back and conclude that my decision to face these musical demons has been a success. That I have cast out these recurring apparitions by staring them down. That I’ve lifted the curse by openly grappling with the ghosts that haunt me. That I finally fucking won!

But I don’t think that’s the case. For one thing, this might be just another respite, longer than most, but still fleeting, a momentary pause until the infernal soundtrack returns. But more importantly, I don’t look at the phenomenon the same way I used to.

Cautious curiosity about a cure seems misplaced. Because after spilling 50,000 words, I no longer think of these songs as foreign agents that occupy me against my will. They’re neither worm nor ghost. Rather, they are simply part of me. And when they take up substantial room in my consciousness, it’s not because they’ve invaded me from without; it’s because I summoned them from within myself. How or why, I do not know. But the truth is, they were already there.

When I hear a song, when the music enters through my ears and registers in my brain, it is a form of ingestion. It entwines itself with my mind. I become one with it, whether hearing it for the first time or the thousandth, whether it remains front and center or lays dormant for years, waiting to reemerge. I am not a mere vessel. The music does not intrude upon me. It is me.

Thus, if I am to learn what it means to live intimately with a single song for a week or more, then instead of trying to understand how or why that song has fastened itself upon me, I need to understand myself. To hear that song is to gaze into a mirror.

Here’s what I know. Sometimes I’m a bit of a of control freak. And sometimes I’m Mr. Don’t Give A Shit. Sometimes either of these traits can work to my advantage, and sometimes they can work against me.

First there’s all the stuff that doesn’t get done. It can make me very happy. Not giving a shit can leave me downright giddy when I think of all the many, many things I don’t need to do or care about. Not caring and not doing are power and freedom. I’m not talking about letting people down or being negligent. I’m talking about unshackling yourself from all the dumb shit that runs amok in our society, about not wasting your time with busy work. Just move past all that. Doing so will bring you a semblance of peace.

It can also save you a buck. Just look at this brief list of things I don’t have (with a “since” date in parentheses): cable tv (2002); a microwave oven (ever); a new car (2005); a smart phone (ever); a tablet (ever); air conditioning, despite living the Chesapeake region (2003); children (ever); a firm belief in God (ca. 1990).

That’s not to say I don’t have my little luxuries. I designed a two-headed shower for my bathroom. It’s just about the best thing in the world when you’re tired or hung over. And a couple of years ago I had a tankless water heater installed so those showers can go on forever.

But in many cases, not having, wanting, or caring makes life a lot easier. Most Americans want too much, and so they end up confusing wants with needs. You need some things, sure. But most of what you have and want are wholly unnecessary. Free yourself from them.

Then again, it’s a fine line. Lazing around on a nice day can be relaxing. But not getting things done can also be very frustrating. Sometimes the simplest tasks will languish. I might not re-string my guitar for months, and either make due with just five strings, or not play at all, even though I enjoy playing. I might need to move something from the upstairs to the basement, get halfway down to the ground floor, put it down, and leave it there for months. Working on my house, which in many cases I’m capable of doing myself, can get delayed by years. And oh, the ideas I have, the writing I’d love to do. Much of it never materializes.

Sometimes the not caring or doing reflects my healthy, happy, laid back nature. But that’s not always easy to separate from the not doing that’s born of anxiety. It’s a fine line between feeling at ease and having a knot in my stomach.

And then of course, there’s the actual doing.

Most people look at my life and think I get a lot done. I earned a Ph.D. in History, which in turn led to a job, tenure, two books and numerous articles, teaching a long list of different courses, seemingly countless committee assignments and such, and a series of promotions. Unrelated to professional work, I co-authored another book, have written hundreds of blogs at my own website, and have been a monthly essayist here at 3 Quarks Daily for nearly a decade. I occasionally travel, and co-founded and often host a weekly poker game that’s nearly ten years running. It’s a lot. Or at least that’s what people tell me.

Yet I often think of myself as a slacker who doesn’t do nearly enough. I’m acutely aware of all the things I want to do but haven’t. It never really stops gnawing at me.

And then there’s the stuff I have done, but am not always happy about.

And then there’s the stuff I have done, but am not always happy about.

On a personal level, I do a lot for friends and family. I’m proud of that. Much of it is fun, and some of it is needed. But some of it feels onerous. I have trouble saying No when someone asks something of me. The same anxieties that prevent me from doing some of the things I want to do, also push me to do things I don’t want or need to do. It’s two sides of the same album.

The nonchalance and the laziness, the rosy cheeked productivity and the tallied obligations, the pride and the joy, and frustrations and the yin-yang of anxiety: it’s all me. And it’s all bound up in these essays, and in my occasional propensity for becoming one with a song for a long time.

After sifting through the songs, and myself, this is what I learned.

Sometimes you’re in control, and sometimes you’re not. Sometimes you have to make it happen, and sometimes you have to let it go.

Easier sung than done.

Post Script: Recently while recently preparing this Epilogue, originally written in 2018, I got a song stuck in my head. It’s been a week now. This is the first time it had happened in over three years. Truly, every ending is a new beginning.

Akim Reinhardt’s website is ThePublicProfessor.com