by Bill Murray

Two minutes after the explosion the fire station alarm rang. The firefighters who scrambled from sleep to the scene, along with the regular overnight shift at reactor four, were among the first fatally irradiated. Unquestioned heroes, they battled the blazes until dawn with no special training for a nuclear accident, in shirtsleeves, using only conventional firefighting methods. They walked amid flaming, radioactive graphite.

Two minutes after the explosion the fire station alarm rang. The firefighters who scrambled from sleep to the scene, along with the regular overnight shift at reactor four, were among the first fatally irradiated. Unquestioned heroes, they battled the blazes until dawn with no special training for a nuclear accident, in shirtsleeves, using only conventional firefighting methods. They walked amid flaming, radioactive graphite.

The power station fire brigade arrived first. Lieutenant Volodymyr Pravik, their commander, saw right away he needed help and called in fire brigades from the little towns of Pripyat and Chernobyl. When Pravik died thirteen days later he was a month shy of age twenty-four.

“We arrived there at 10 or 15 minutes to two in the morning,” said fire engine driver Grigorii Khmal.

“We saw graphite scattered about. Misha asked: Is that graphite? I kicked it away. But one of the fighters on the other truck picked it up. It’s hot, he said. The pieces of graphite were of different sizes, some big, some small enough to pick them up….

“We didn’t know much about radiation. Even those who worked there had no idea. There was no water left in the trucks. Misha filled a cistern and we aimed the water at the top. Then those boys who died went up to the roof – Vashchik, Kolya and others, and Volodya Pravik…. They went up the ladder … and I never saw them again.”

Another fireman told the BBC, “It was dark because it was night. On the other hand, you could see and even recognize a person from 10 to 15 meters. It was if (sic) the sun was rising, but with a strange light.”

They climbed to the roof of what was left of reactor four, preventing fire from spreading to the other three reactors and so preventing what could have been a truly ghastly night. By 5:00 a.m. all the fires were out save for the one in the reactor. That fire burned for ten days. It took 5000 tons of sand, boron, dolomite and clay dropped from helicopters to put it out.

The political heart of the U.S.S.R. was aware of the accident within an hour and a half. V. V. Maryin, the head of the nuclear power sector of the CPSU Central Committee got a call at three o’clock in the morning.

The political heart of the U.S.S.R. was aware of the accident within an hour and a half. V. V. Maryin, the head of the nuclear power sector of the CPSU Central Committee got a call at three o’clock in the morning.

His wife Alfa Fedorovna Martynova: “On 26 April 1986 at 0300 hours, the intercity phone rang in our house. Bryukhanov was calling Maryin from Chernobyl. When he finished the conversation, Maryin told me: ‘A horrible accident at Chernobyl….’ He quickly dressed and called for his car. Just before he left, he called … Frolyshev. He in turn called Dolgikh. Dolgikh called Gorbachev and the members of the politburo.”

The leadership reacted fast, dispatching teams to the scene, but remained outwardly opaque for days. When Sweden raised the alarm two days later, the rest of the world began asking questions, forcing the Politburo into an emergency meeting.

What to divulge? As little as possible, they decided. The evening of the day they evacuated Pripyat, they read this on Vremya, the nightly TV newscast:

“An accident has taken place at the Chernobyl power station, and one of its reactors was damaged. Measures are being taken to eliminate the consequences of the accident. Those affected by it are being given assistance. A government commission has been set up.”

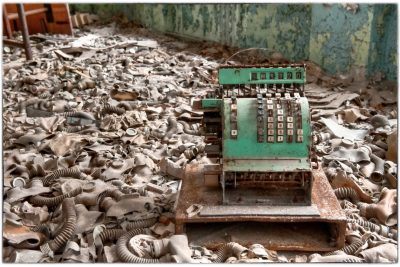

Censors assured nothing more was reported, and here is the irretrievable breach of trust, the crime the regime could never put right: Putting its reputation before its citizens’ health. Because between the accident and the announcement on Vremya, while local officials remained silent, fire raged in the blown open reactor four. And families across Pripyat, after a winter pent up in apartment blocks, basked unaware in the warm spring sunshine.

•••••

Western Europe worked itself into a great frenzy. Officials tested people arriving from Kyiv and found that those arriving before May 1st brought no radiation on their skin, hair and clothing but those who were in Kyiv from May 1st on, did. They determined what types of radionuclides were released and decided those would only be released at temperatures indicating that the reactor core had at least partially melted. The Polish government decided to hand out iodine tablets to children on their border near Ukraine. For weeks Europeans drank powdered milk and scrubbed their vegetables. Some places banned fresh produce and milk.

Western Europe worked itself into a great frenzy. Officials tested people arriving from Kyiv and found that those arriving before May 1st brought no radiation on their skin, hair and clothing but those who were in Kyiv from May 1st on, did. They determined what types of radionuclides were released and decided those would only be released at temperatures indicating that the reactor core had at least partially melted. The Polish government decided to hand out iodine tablets to children on their border near Ukraine. For weeks Europeans drank powdered milk and scrubbed their vegetables. Some places banned fresh produce and milk.

Thirty-four years on, as we follow catastrophes in real time, it’s hard to remember the closed nature of the Soviet system in Gorbachev’s early days. With complicit local leaders, they kept word of the accident from Kyiv, 55 miles away, and Minsk, about 215 miles away, long enough for the annual May Day parades to be held on open, radioactive streets five full days later, three days after a ten-kilometer circle around reactor four was evacuated. Apparently to make everything appear under control.

The day after the parade, May 2nd, a further 30 kilometer zone was designated for evacuation. On May 6th, after eleven days, they closed the schools in Kyiv and the radio urged everyone to stay indoors and not to eat leafy greens. It took eighteen days for Gorbachev to go on TV with his own account of the disaster.

•••••

While political Moscow showed itself ham-handed, the medical establishment proved adroit. By nightfall on the first day, only sixteen-odd hours after the blast, they’d flown 129 patients to hospitals. 170 more followed the next day.

Specialized first responders flew to Chernobyl in half a day. Medical units gathered in Moscow scant hours after the accident, before dawn, and arrived in Kyiv at 11:00 a.m. They examined over a thousand people.

Ultimately 5000 doctors and nurses descended on the region, especially therapeutic radiologists and hematologists. In Moscow some 300 more provided care.

Local officials seized up with panic straightaway. They didn’t keep people indoors. They tried to hide the accident entirely. Some scoffed at worried residents in a bullying, Soviet way. “(A)ren’t you used to that? It was a steam discharge from the power plant.”

Local officials seized up with panic straightaway. They didn’t keep people indoors. They tried to hide the accident entirely. Some scoffed at worried residents in a bullying, Soviet way. “(A)ren’t you used to that? It was a steam discharge from the power plant.”

At the plant, bosses froze in place, eyes wide, far out of their depth. For the first day they misrepresented the severity of the emergency to Moscow and throughout they underestimated the calamity at hand. It took national officials arriving from the capital to comprehend the catastrophe.

You can blame Moscow for just about everything, from its political opacity before the rest of the world right through to the very design of the reactor. But they put on a pretty good evacuation, in two hours and twenty minutes start to finish.

Moscow’s investigating committee of ministers and deputies made the decision to evacuate Pripyat late Saturday night, a few hours after their arrival and just 20 or 21 hours after the blast. The civil defense and medical people insisted on it.

And still the fire in reactor four burned intensely, incredibly hot. It’s strange, but that probably spared Pripyat, for the heat rose as if through a smokestack, lifting radioactive dust and particles a kilometer into the air, far above and beyond town.

Since the initial radiation sailed high over Pripyat and away, some of the Moscow committee hoped radiation levels would settle down before they’d have to evacuate. But the wind changed direction during the night prompting the decision, nominally made by the head of Moscow’s scientific team, a man named Valeriy Legasov. Who now had some daunting logistics to get right, and fast.

Comrade Legasov summoned transportation. Two diesel trains called at the Yanov station, right up by the plant, providing 1500 seats. The team calculated the number of people in an apartment building times the 23 buildings, divided by the number of seats on a bus and guessed they’d need something like twelve hundred buses. Calls went out. Before dawn a queue of big yellow city buses began to assemble outside town, driven up from Kyiv.

Comrade Legasov summoned transportation. Two diesel trains called at the Yanov station, right up by the plant, providing 1500 seats. The team calculated the number of people in an apartment building times the 23 buildings, divided by the number of seats on a bus and guessed they’d need something like twelve hundred buses. Calls went out. Before dawn a queue of big yellow city buses began to assemble outside town, driven up from Kyiv.

Officials asked for volunteer drivers and some of the confirmed cases of radiation sickness were among bus drivers who thought the whole business was a lark. They drove up from Kyiv Saturday night, played soccer with the other drivers and stood and watched the reactor burn, knowing little of the danger.

Unfortunately for the evacuation effort, reactor four is right between Pripyat and Kyiv and the only road connecting the two runs directly past the reactor. Under the circumstances, that road was going to have to do. It was better than herding the whole town onto the radioactive train platform.

In fact, the evacuation team caught a series of huge breaks. If the U.S.S.R.’s third largest city hadn’t been a scant 70 miles down the road with the resources that come with a population of 2.3 million people the evacuation would have taken far longer.

The Soviets’ lag in consumer culture also played to the planners’ benefit. Because few people had cars or houses, the evacuation moved forward in buses from apartment blocks, an efficient combination for which the authorities could thank their lucky red stars.

Thirty six hours after the accident they evacuated Pripyat quickly and calmly under the eyes of the militia. Once the evacuation started they got everybody out in three hours. Authorities said 1,216 buses and 300 trucks were used. The convoy stretched twenty kilometers along the entire road from Pripyat back to Chernobyl.

Thirty six hours after the accident they evacuated Pripyat quickly and calmly under the eyes of the militia. Once the evacuation started they got everybody out in three hours. Authorities said 1,216 buses and 300 trucks were used. The convoy stretched twenty kilometers along the entire road from Pripyat back to Chernobyl.

No one thought to change the bus tires at the edge of the zone. Radioactivity measured on the asphalt required them to wash down the roads in Kyiv for months.

•••••

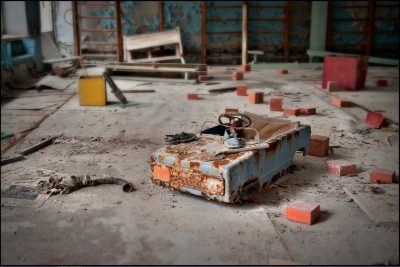

In the Soviet Union the waiting list for little East German Trabant sedans was ten years in 1987. It was up to fifteen years for domestic Ladas and Czechoslovakian Skodas. Not many people in Pripyat had their own car in 1986. Those who did were naturally keen to flee in their cars and not the buses. With your car, you could take more of your things. You could take your pets.

Maybe that’s why the authorities told people they’d only be away for a few days. In the panic that would follow the truth, people would try to bring out more things, and slow down the evacuation. And besides, they’d be carrying every kind of radioactive thing out into the larger population.

Everyone had to take the buses. Family dogs ran after the buses for a distance, then fell back. They sent in hunters with shotguns.

A month later a hundred mile perimeter of barbed wire and watchtowers spanned the exclusion zone, gulag-style. Not to keep people in, but to make sure they stayed out.

•••••

Chernobyl bedeviled Moscow to the bitter end, right up to burying the victims’ bodies. A. M. Khodakovsky, the man in charge of burying the dead, said “When it learned that the bodies were radioactive, the public health station demanded that concrete rafts be made at the bottom of the graves, as underneath the nuclear reactor, so that the radioactive fluids from the corpses would not go off into the groundwater. This was impossible, blasphemous, we argued with them for a long time. Finally, we agreed that the highly radioactive corpses would be soldered into zinc caskets. That is what we did.”

Chernobyl bedeviled Moscow to the bitter end, right up to burying the victims’ bodies. A. M. Khodakovsky, the man in charge of burying the dead, said “When it learned that the bodies were radioactive, the public health station demanded that concrete rafts be made at the bottom of the graves, as underneath the nuclear reactor, so that the radioactive fluids from the corpses would not go off into the groundwater. This was impossible, blasphemous, we argued with them for a long time. Finally, we agreed that the highly radioactive corpses would be soldered into zinc caskets. That is what we did.”

They were laid into the earth in two rows in a “special area” of Mitinskoye Cemetery. Headstones of white marble recorded their names, dates of birth and death. Nothing more.

•••••

Mikhail Gorbachev used the 20th anniversary of the accident in April 2006 to finger Chernobyl as a turning point in the collapse of the Soviet Union. “The Chernobyl disaster,” he wrote, “opened the possibility of much greater freedom of expression, to the point that the system as we knew it could no longer continue.” He wrote that he “started to think about time in terms of pre-Chernobyl and post-Chernobyl.” He protested his administration’s innocence, insisting “nobody knew the truth.”

But within sixteen-odd hours of the blast Moscow’s radiation hospital had 129 patients already under treatment, airlifted from the blast site. The Kremlin’s hand-picked team gave the order to evacuate Pripyat less than twenty-four hours after the blast.

It may serve the former General Secretary to see the collapse of the USSR on his watch as caused by cataclysm, an event with effects far beyond the control of a mortal leader. But Gorbachev didn’t grant the “much greater freedom of expression.” Chernobyl set it in train. It rode in on the shock tide of the government’s opacity, delay and insufficient response in a vital health emergency.

•••••

Further reading to bring this to the present: A Message from the Frontlines of the Pandemic.