by Rafaël Newman

Some years ago, a friend told me about his dilettantish taste for nicotine, indulgence in which, however, he noted ruefully, was often thwarted by his young daughter. He supposed the vehemence of her protests derived, simply, from a concern for his health – to which I responded, perhaps: but that there might also be a further factor. His daughter, I reminded him, was just barely prepubescent, and thus newly arrived in what classical psychoanalysts call the “latency phase”, in which the para-erotic pulsions characterizing the various stages of her psychosexual development to date, and directed at her opposite-sex parent, the putative object of her nascent desire, are in retreat under the dawning realization that she is unlikely to be successful in her Oedipal struggle; and so she begins instead to bend to the will of a superego offering a compensatory identification with her triumphant rival, her mother. (This was before I had read Didier Eribon.) As a consequence, I concluded, his daughter was in the midst of developing prohibitive feelings of disgust at the merest suggestion of the desire she was busy repressing, and was thus likely to react with exaggerated horror at any sign of eroticism on the part of her erstwhile object.

Some years ago, a friend told me about his dilettantish taste for nicotine, indulgence in which, however, he noted ruefully, was often thwarted by his young daughter. He supposed the vehemence of her protests derived, simply, from a concern for his health – to which I responded, perhaps: but that there might also be a further factor. His daughter, I reminded him, was just barely prepubescent, and thus newly arrived in what classical psychoanalysts call the “latency phase”, in which the para-erotic pulsions characterizing the various stages of her psychosexual development to date, and directed at her opposite-sex parent, the putative object of her nascent desire, are in retreat under the dawning realization that she is unlikely to be successful in her Oedipal struggle; and so she begins instead to bend to the will of a superego offering a compensatory identification with her triumphant rival, her mother. (This was before I had read Didier Eribon.) As a consequence, I concluded, his daughter was in the midst of developing prohibitive feelings of disgust at the merest suggestion of the desire she was busy repressing, and was thus likely to react with exaggerated horror at any sign of eroticism on the part of her erstwhile object.

“You mean,” he said, “she interprets my cigarette smoking as a manifestation of such eroticism?”

“Yes,” I said. “Because it involves you repeatedly touching yourself with pleasure.”

I’ve been recalling that conversation a lot lately, as the injunction, issued by a global superego, to avoid doing precisely this – touching oneself, specifically one’s face – has made many of us hyper-aware of our tendency to do so, and lent an ostensibly banal behavior the allure of the forbidden.

At the moment, the central aperçu of that long-ago encounter with my friend seems truer than ever: that there exists a veritable erotics of face-touching; that the movement of one’s hand to one’s face, and especially to the area of the mouth, chief among the various membranes on or about the face and centrally implicated in the variously erotically charged activities of eating, licking, sucking, and kissing, may serve as a signal, whether conscious or not, of sexual readiness; and that the prohibition of such self-touching is likely to arouse memories of a much earlier psychosexual phase, and to give rise to frustration, rebelliousness, and a will to act out, all sourced from a dormant but still powerful infantile self – and given extra dynamism by one’s intervening forays into a franker genital self-pleasuring, fired by sense memories of all the duplicity and shame traditionally attendant on masturbation.

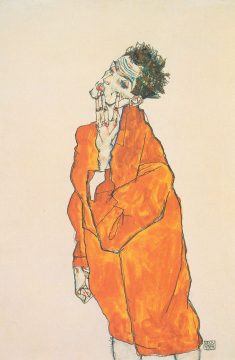

I am evidently not alone in noticing the latent erotic potential of face-touching – the modern iconography is narrow, but vivid. There are the languid subjects of Egon Schiele, of course, often only half clothed, who seem explicitly to be displacing their onanistic gestures from below to above. There are the nudes in Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze, arrayed on either side of a gigantic, libidinous ape, framing their faces with their hands in various states of ecstasy or morbid self-involvement. There is Peter Hujar’s 1969 “Orgasmic Man”, a series of close-ups of men experiencing sexual climax, one of whom, the back of his hand resting delicately against his cheek, achieved subsequent notoriety on the cover of Hanya Yanagihara’s excruciating A Little Life (2015), an epic of self-harm and interior decoration. And there is Meg Ryan, faking an orgasm in a deli in When Harry Met Sally (1989), running her fingers through her hair: “I’ll have what she’s having!”

I am evidently not alone in noticing the latent erotic potential of face-touching – the modern iconography is narrow, but vivid. There are the languid subjects of Egon Schiele, of course, often only half clothed, who seem explicitly to be displacing their onanistic gestures from below to above. There are the nudes in Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze, arrayed on either side of a gigantic, libidinous ape, framing their faces with their hands in various states of ecstasy or morbid self-involvement. There is Peter Hujar’s 1969 “Orgasmic Man”, a series of close-ups of men experiencing sexual climax, one of whom, the back of his hand resting delicately against his cheek, achieved subsequent notoriety on the cover of Hanya Yanagihara’s excruciating A Little Life (2015), an epic of self-harm and interior decoration. And there is Meg Ryan, faking an orgasm in a deli in When Harry Met Sally (1989), running her fingers through her hair: “I’ll have what she’s having!”

Then, too, there are renowned celebrity portraits, what W.H. Auden might have called “private faces in public places”: organized glimpses of interiority, in which a hand placed on a cheek or under a chin communicates reflection, seriousness à la Rodin, or readiness to make mischief: Susan Sontag, wryly displaying her exotic features with a long-fingered hand; inevitably memed images of Michel Foucault studiously tweaking his cleft chin; Meryl Streep, by Annie Leibovitz, stretching the skin of her face into a parody of the thespian’s mask. The face-touching stage-managed here is evidently intended to render the subject more familiar, more “accessible”: more personal, finally, because caught in the act of (intellectual, rather than overtly erotic) self-relation.

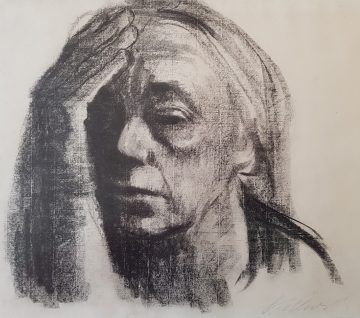

But the tradition also comprises celebrated images of a bleaker inwardness, in which a hand over an eye, against a cheek or on a forehead conveys shame, melancholy, or outright mourning: see Michelangelo’s condemned man on the Day of Judgment; various of Käthe Kollwitz’s self-portraits, in which she broods on losses both national and personal; or, most notoriously, Edvard Munch’s 1893 “Skrik” (“The Scream of Nature”, AKA “The Scream”), endlessly conscripted as the prescient emblem of a coming age vowed to fragmentation and horror.

But the tradition also comprises celebrated images of a bleaker inwardness, in which a hand over an eye, against a cheek or on a forehead conveys shame, melancholy, or outright mourning: see Michelangelo’s condemned man on the Day of Judgment; various of Käthe Kollwitz’s self-portraits, in which she broods on losses both national and personal; or, most notoriously, Edvard Munch’s 1893 “Skrik” (“The Scream of Nature”, AKA “The Scream”), endlessly conscripted as the prescient emblem of a coming age vowed to fragmentation and horror.

Not all face-touching, in other words, is erotic. Indeed, the repertory of expressions in English involving the act tends to deploy it as a metaphor of despair rather than of delight: to put one’s head in one’s hands; to pull one’s hair out; to tear one’s cheeks – all doubtless calques of actual traditional mourning practice. (The French too, by the way, clutch their heads in anguish, but, true to form, reach for their feet in delight.) And yet in actual lived practice, the gesture has an ostensibly more mundane application. In an age of selfies, in which a “profile picture” is de rigueur on the various social media platforms that serve, these days more than ever, as forum and oracle, I have noticed in myself a preference for images in which the subject’s face is shown in conjunction with one of their hands, whether actually touching the face or merely gesticulating near it. It’s the posture I have tended to adopt, or subsequently select, for my own profile pictures, no doubt more for the dynamic flair it lends than out of any (overt) desire to convey erotic aptitude – we’re talking Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn here, not Tinder. And yet there is an undeniable eros, in the Socratic, pedagogical sense, in this combination of the face, repository of personality and aesthetic appeal and site of language production, and the hand, instrument of the brain housed behind that face, executor of its commands, and practical expositor of its ideas. “Omne tulit punctum qui miscuit utile dulci,” says Horace, in his Ars Poetica, a manual for writers: mix the useful with the sweet, and you’ll score at every meet. The useful hand (instruction) and the sweet face (pleasure) are a team as effective in rhetoric as in poetry: see Terry Eagleton and Rüdiger Safranski, among others, on the power and perils of an aestheticized politics. More positively, the juxtaposition of face and hand conjures up the union of contemplation and action that Marx invokes in his Theses on Feuerbach, calling on philosophers to change the world. It is the sign of that political activity arising out of philosophical thought prescribed by Hannah Arendt for a world consumed by alienated labor, and belabored by consumption.

In Hannah Arendt, her 2012 film biography of the German-American thinker, Margarethe von Trotta presents Arendt during the most notorious period of her life, her coverage of the trial of Adolf Eichmann for the New Yorker in the 1960s, which led to the publication of Eichmann in Jerusalem and its celebrated account of “the banality of evil”. A film reviewer in 2013 noted that von Trotta was also the director of a biopic devoted to Rosa Luxemburg, a progressive forebear of Arendt’s with a much more explicitly activist bent, played in that film, as it happens, by Barbara Sukowa, the same actress who personifies Arendt in the later work. The reviewer wrote: “Arendt is a more challenging cinematic portrait. Her outwardly bookish existence challenges the ancient distinction between active and contemplative ways of living, but the work of thinking is notoriously difficult to show. In this case, it looks a lot like smoking, with intervals of typing, pacing or staring at the ceiling from a daybed in the study.”

Smoking and thinking, thinking as smoking: the hand raised repeatedly to the face, to the mouth, delivering to the system a combination stimulant and tranquilizer. The hand that might also be used for proverbial head-scratching, as if to activate contemplation; to cup or prop the chin, as if the weight of thought needed extra support; to shield the eyes against the incursions of the outside world, and thus foster the serenity necessary for reflection. Smoking as the outward manifestation of philosophical activity, which is, in Plato’s Socratic formulation, the practice of death: the contemplation of the finitude of human life, and the preparations for taking leave of it, in a process with its own idiosyncratically erotic pedagogy, tending to the reanimation of knowledge obscured within us since (re)birth and aspiring to the abstract even as it recognizes the concrete limitations of earthly existence.

No wonder my friend’s young daughter was incensed by his smoking. Now if only we, too, can find a way to awaken ourselves to contemplation today, and eventually to action, without all too actively preparing for death with the consumption of controlled substances – or by recklessly touching our faces.

Thanks to Hella Wiedmer-Newman for research and to Suleika Batthyany, Frances Newman, and Caroline Wiedmer for comments.