by Michael Liss

I am one of those people who cannot sit still. I wasn’t good at it as a child, and as the decades pass, every indication is that I will never be good at it. I suspect I inherited this from my father, who lacked a single iota of Sitzfleisch, and have passed on the gene to one of my children (no need to name names here, she knows who she is and who to blame.)

I am one of those people who cannot sit still. I wasn’t good at it as a child, and as the decades pass, every indication is that I will never be good at it. I suspect I inherited this from my father, who lacked a single iota of Sitzfleisch, and have passed on the gene to one of my children (no need to name names here, she knows who she is and who to blame.)

I did fully disclose this to my wife before we were married, not that she needed to be told. She hangs in there, with occasional moments of thoroughly merited exasperation. Weekdays tend to take care of themselves, as we both work fairly long hours. Weekends, on the other hand, can be problematic, so I’m fairly sure she likes it when I leave to go running in the park with my group. As I’m not the greyhound I used to be, this can take quite a bit of time, especially when you add in a stop on the way back for some empty calories. Before you know it, it’s almost Noon. Sitzfleisch problem solved, at least until 1:30.

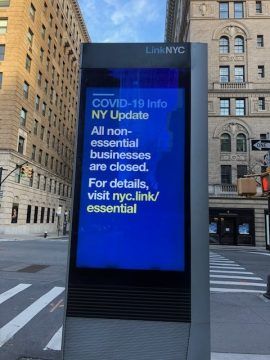

Of course, this was all before Coronavirus, all before I was deemed “non-essential” and even officially old. I’m not sure where this “old” nonsense came from, but the solicitude for my health and wellbeing merely as a function of an arbitrary number is a little hard to take. All of a sudden there seem to be an awful lot of things I’m not supposed to be doing. I never thought “aging in place” was meant to be taken literally.

Of course, this was all before Coronavirus, all before I was deemed “non-essential” and even officially old. I’m not sure where this “old” nonsense came from, but the solicitude for my health and wellbeing merely as a function of an arbitrary number is a little hard to take. All of a sudden there seem to be an awful lot of things I’m not supposed to be doing. I never thought “aging in place” was meant to be taken literally.

This is such a petty complaint. In my City, my Mighty Gotham, we are apparently all aging in place, all taking care by taking shelter. This just doesn’t suit us well. Sitzfleisch is for suburbanites.…the kind of folks who drive a football field’s distance for a quart of milk and have 5,000 square-foot homes with enormous refrigerators, storage space, and a game room where the kids can fight with each other from another zip code.

If you live in the City and have a 5,000 square foot home, you have other homes as well, and are almost certainly in one of them. For the rest of us, we have joined the battalions of the shut-ins and shut-downs. Our buildings and businesses are shut down. Broadway and high culture closed. There are barred doors to some of the highest-end retail shops in the world (often announced by plain-white signs on doors). Diners and pizza parlors open for take-out only. Starbucks closed. Thousands of little shops, also deemed non-essential, sadly stare out with empty eyes. Some of those eyes will never see again.

This nags at me, this sense that Coronavirus will be like smallpox, and, if we get through it, there will still be scars that will not fade. We will be changed.

Teddy Roosevelt once said that “[c]haracter, in the long run, is the decisive factor in the life of an individual and of nations alike.” Crises have a way of finding the core—some can keep their eyes on the goal and rise above it, others melt down and blather.

We’ve been fortunate here. Andrew Cuomo has risen to the occasion. Fifty thousand health-care professionals have come out of retirement to put themselves in harm’s way. Our cops, firefighters, transit workers, hospital personnel and EMTs have been extraordinary. But what makes this situation far more complicated is that our success in handling this war can’t be solved with just logistics and heroics. The rest is up to us: We need to take care of ourselves and take care of others. We need to be a true community, albeit at a six-foot length.

For non-essential me, working remotely from home, with my essential-but-also-working-remotely wife, this means adjusting to her perceptive (but wildly improbable) suggestion, “You need to develop some Sitzfleish.” I’m still going running, but alone now, so my kinship is reduced to those strangers who pass me (with proper social distancing), and sightings of two regulars, “Bare-Chested Guy” and Mr. G, redoubtable meteorologist for a local TV station.

That 90 minutes of clean air and clear mind helps a bit with the Sitzfleish problem, but it’s only 90 minutes. I need other distractions. I was reading Kyle Harper’s The Fate of Rome, but that turned out to be a spectacularly poor choice: how climate change and pandemics brought down the Roman Empire.

I think we would all agree that’s a no, so I turned to Netflix and YouTube, enlisting alongside Horatio Hornblower, in the terrific eight-part series starring Ioan Gruffudd. Duty, loyalty, cannons, duels, Napoleon, bravery, comradeship, Frogs and Lobsters. There was an episode with the plague…but everyone lived. Still, how many times can you watch derring-do and men yelling “fire”?

Quite a lot, as it turns out, but, ultimately, I turned to David Lynch’s astonishing, and astonishingly beautiful The Straight Story.

Based on a true story, it literally is about Sitzfleisch—an old man sitting on a small tractor as he drives 240 miles from Laurens, Iowa to Mount Zion, Wisconsin, to find and reconcile with his ailing brother. In a perfect bit of casting, Lynch picked Richard Farnsworth (who spent decades in obscurity as a stunt man before an Oscar nomination for Comes a Horseman) to play Alvin Straight.

Farnsworth’s face alone is worth the visit; the sun has baked it into a pair of knowing blue eyes set in a glorious map of deep wrinkles. Out of it comes a reedy tenor and an almost sideways way of speaking—unlike many actors, Farnsworth doesn’t rush his lines. Alvin’s hips are shot from a lifetime of labor, and he can no longer pass the eye test for a driver’s license, but, when he hears that his older brother Lyle has had a stroke, he’s impelled to make the trip. He sends his developmentally disabled daughter Rose (Sissy Spacek, in an exquisitely self-effacing performance) to stock up on wieners and liverwurst (leading to a very witty scene where neither the checkout clerk nor Rose quite understand each other), puts a hitch on a handmade mobile trailer, plants himself on a tractor, and begins his trek.

He doesn’t get very far, the tractor being perhaps even older than he. After a swap into a more roadworthy John Deere, off Alvin goes, up and down gentle hills through the farm country. When the light fails, he sleeps by the side of the road, cooks the wieners with a stick over an open fire, and lights up a cigar. Farnsworth has a wonderful emotional stillness about him in these moments—he’s at home on the road.

The Straight Story is really a series of small, perfect, vignettes. Some are gently comic, but this is not a road movie, and it’s certainly not a bucket-list film. Everyone is treated with respect both by the camera and the script. Lynch is secure enough to let his largely starless cast be themselves and has enough discipline to let the scenery speak for itself.

At some point, while you are watching, you might ask yourself when the action will begin. In some respects, it never does. This is the action. Nothing wasted. Everywhere, there’s simple living, common courtesy, and a friendly hand. Alvin’s a proud man, and independent, and those who help have the uncommon gift of not making it charity.

What you find is that it isn’t charity at all. The movie doesn’t infantilize Alvin because he’s old. He is old, and worn, and physically diminished, but he’s not done. He’s still competent. He can still build things, use a welding torch, a shotgun, and his quick wits and a sharp, knowing eye. All those years of living, the good and the bad, left him something to give, and he does. There’s a tranquil evening with a runaway pregnant teen, a moment in a church graveyard when a priest comes out to talk, a pair of feuding brothers, and a stunner in a bar where he shares memories with a fellow World War II vet.

Everything takes time. Like the gentle score by Angelo Badalamenti (who also did Twin Peaks) and the speed of Alvin’s mower, the story just unfolds with the passing landscape, as he makes his way to Lyle. He survives a mechanical failure and near crash, and, while his tractor is repaired, stays with a retired John Deere employee named Danny Riordan and his wife Darla. The couple’s interactions made me smile, particularly when Darla gently teases Danny about being a soft touch, and lets him know she’s glad she married him—despite what her mother said.

Eventually, Alvin gets back on the road. It’s a long journey, and I won’t spoil the ending for you. I’ll simply say that, in a time of chaos, of isolation and uncertainty, this movie reminded me of things that most of us want—family, friendship, community.

I don’t know what’s on the other side of the Coronavirus pandemic, but I hope it’s something as simple as Alvin’s parting words to Danny:

“I want to thank you for your kindness to a stranger.”