by Derek Neal

Read Part 1 here.

In The File on H, Ismail Kadare shows his appreciation of epic poetry and attempts to incorporate aspects of orality so that the form of the novel reflects its content. The plot is relatively simple: two Harvard scholars (modelled on Parry and Lord) travel to Albania to record singers of epic poetry in the 1930s. The local townspeople are suspicious, suspecting some sort of espionage, but also intrigued, leading to a series of outrageous situations—the governor of the small town has two spies track Bill and Max, while the governor’s wife imagines a steamy affair with one of them, then the other. After they record a couple of poets in Albanian, a Serbian monk hatches a plan to destroy the tapes. The epic singers fear that if they are recorded, their voices will be “walled up,” and they will no longer be able to sing. On the surface, these are amusing tales, but they get at deeper truths—the paranoia of Enver Hoxha in communist Albania, the appeal of the exotic foreigner, the deep historical and political tensions between Serbia and Albania, and the impact of technology on art, communication, and identity. The plot unfolds as a sort of oral and textual history, with certain parts written from a close third person point of view, while other sections are presented as reports from the spies, newspaper clippings, transcribed dialogue, journal entries, and oral speech as one would see in a filmscript. In this way, Kadare filters his novel through an oral prism—when we are reading, it is almost never “primary” text but frequently a version of “hearsay.” We might read one character’s written summary of what another character said verbally (like a spy report that transcribes overheard dialogue), or it might be speech that Kadare visually presents like a play or filmscript, and that speech might include things the character has overheard from others. It sounds confusing, but when you read it, it’s easy to follow and hugely entertaining; Kadare is a master storyteller who can move between many different registers. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Decay Saturated. Vermont, April, 2017.

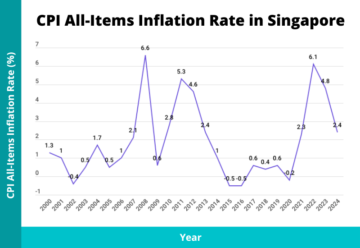

Sughra Raza. Decay Saturated. Vermont, April, 2017. If you in any way follow AI policy, you will likely have heard that the EU AI Act’s Code of Practice (CoP) was released on July 10. This is one of the major developments in AI policy this year. 2025 has otherwise been fairly negative for AI safety and risk – the Paris AI summit in February

If you in any way follow AI policy, you will likely have heard that the EU AI Act’s Code of Practice (CoP) was released on July 10. This is one of the major developments in AI policy this year. 2025 has otherwise been fairly negative for AI safety and risk – the Paris AI summit in February

I write this not to counter Holocaust deniers. That would be a waste of time; the criminally insane will spew their fantastical vitriol no matter what you tell them. Nor do I write this in the spirit of “Never forget!” As a historian I am committed to remembering this and many more genocides, particularly the most devastating and thorough genocide of all: the European genocides of Indigenous societies. At the same time, I understand the ultimate futility of admirable slogans such as “Never Forget!” For everything is forgotten, eventually. Everything and everyone.

I write this not to counter Holocaust deniers. That would be a waste of time; the criminally insane will spew their fantastical vitriol no matter what you tell them. Nor do I write this in the spirit of “Never forget!” As a historian I am committed to remembering this and many more genocides, particularly the most devastating and thorough genocide of all: the European genocides of Indigenous societies. At the same time, I understand the ultimate futility of admirable slogans such as “Never Forget!” For everything is forgotten, eventually. Everything and everyone.

In reading about attachment theory,

In reading about attachment theory,

On a sunny Saturday towards the end of last month we took a train to Moutier in the west of Switzerland, half an hour from the French border, to attend an opera in a shooting range. We had tickets to hear my friend

On a sunny Saturday towards the end of last month we took a train to Moutier in the west of Switzerland, half an hour from the French border, to attend an opera in a shooting range. We had tickets to hear my friend

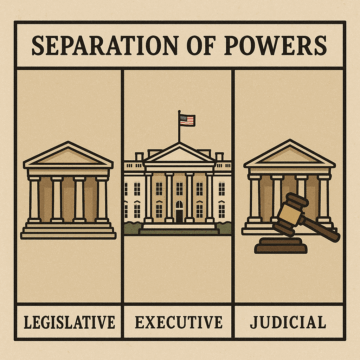

Americans learn about “checks and balances” from a young age. (Or at least they do to whatever extent civics is taught anymore.) We’re told that this doctrine is a corollary to the bedrock theory of “separation of powers.” Only through the former can the latter be preserved. As John Adams put it in a letter to Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, later a delegate to the First Continental Congress, in 1775: “It is by balancing each of these powers against the other two, that the efforts in human nature toward tyranny can alone be checked and restrained, and any degree of freedom preserved in the constitution.” As Trump’s efforts toward tyranny move ahead with ever-greater speed, those checks and balances feel very creaky these days.

Americans learn about “checks and balances” from a young age. (Or at least they do to whatever extent civics is taught anymore.) We’re told that this doctrine is a corollary to the bedrock theory of “separation of powers.” Only through the former can the latter be preserved. As John Adams put it in a letter to Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, later a delegate to the First Continental Congress, in 1775: “It is by balancing each of these powers against the other two, that the efforts in human nature toward tyranny can alone be checked and restrained, and any degree of freedom preserved in the constitution.” As Trump’s efforts toward tyranny move ahead with ever-greater speed, those checks and balances feel very creaky these days.

Gozo Yoshimasu. Fire Embroidery, 2017.

Gozo Yoshimasu. Fire Embroidery, 2017.