by Dwight Furrow

A life in which the pleasures of food and drink are not important is missing a crucial dimension of a good life. Food and drink are a constant presence in our lives. They can be a constant source of pleasure if we nurture our connection to them and don’t take them for granted.

A life in which the pleasures of food and drink are not important is missing a crucial dimension of a good life. Food and drink are a constant presence in our lives. They can be a constant source of pleasure if we nurture our connection to them and don’t take them for granted.

Because food and drink are an easily accessible source of pleasure, barring poverty or disease, to care little for them is a moral failure with consequences not only for the self but for others around us. However, to nurture that connection to everyday pleasure requires thought and restraint. Pleasure can be dangerous when pursued without reason and self-control. Addictive pleasures damage us and everyone around us. Addicts, in fact, cannot feel pleasure as readily as the non-addicted and require increasing levels of stimulation to find satisfaction. Addictions and compulsions are pathological and are no model for the genuine pursuit of pleasure. Thus, we need to make a distinction between pleasure that we get from thoughtless, compulsive consumption, and pleasure that is freely chosen. Pleasure freely chosen is actually a good guide to what is good for us and what should matter to us.

This emphasis on freely chosen pleasure is important not only for keeping us healthy but because certain kinds of pleasures are deeply connected to our sense of control and independence. Some of the pleasures in life come from the satisfaction of needs. When we are cold, warm air feels good. When we are hungry even very ordinary food will taste good. But such enjoyment tends to be unfocused and passive. We don’t have to bring our attention or knowledge to the table to enjoy experiences that satisfy basic needs. We are hard-wired to care about them and our response is compelled.

However, many pleasures are not a response to need or deprivation. We have to eat several times a day, but we don’t have to eat well several times a day. Pleasure freely chosen is essential to a good life because it expresses our independence from need. Read more »

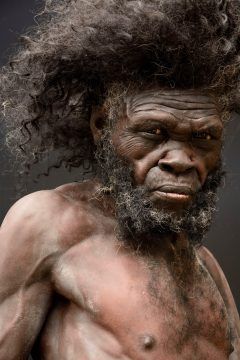

At the beginning of our story—paraphrased from an origin story remembered by a

At the beginning of our story—paraphrased from an origin story remembered by a  There is a minor American myth about shame and regret. It goes like this.

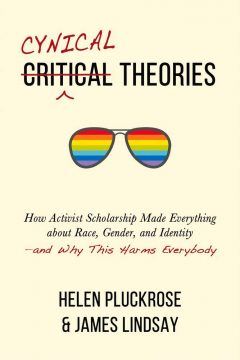

There is a minor American myth about shame and regret. It goes like this. The most charitable, forward-looking take on the science wars of the 90s is Stephen Jay Gould’s, in The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister’s Pox (2003), a delightful book about dichotomies between the sciences and humanities. His diagnosis is primarily that scientists have taken too literally or too seriously some fashionable nonsense, and overreacted; and if everybody can just calm down already, things will be alright and both sides could “break bread together” (108). Gould saw the science wars themselves as a marginal and slightly comical skirmish, almost a mere misunderstanding. “Some of my colleagues”, he said,

The most charitable, forward-looking take on the science wars of the 90s is Stephen Jay Gould’s, in The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister’s Pox (2003), a delightful book about dichotomies between the sciences and humanities. His diagnosis is primarily that scientists have taken too literally or too seriously some fashionable nonsense, and overreacted; and if everybody can just calm down already, things will be alright and both sides could “break bread together” (108). Gould saw the science wars themselves as a marginal and slightly comical skirmish, almost a mere misunderstanding. “Some of my colleagues”, he said, Sughra Raza. Light As a Feather. Boston, Sept 2020.

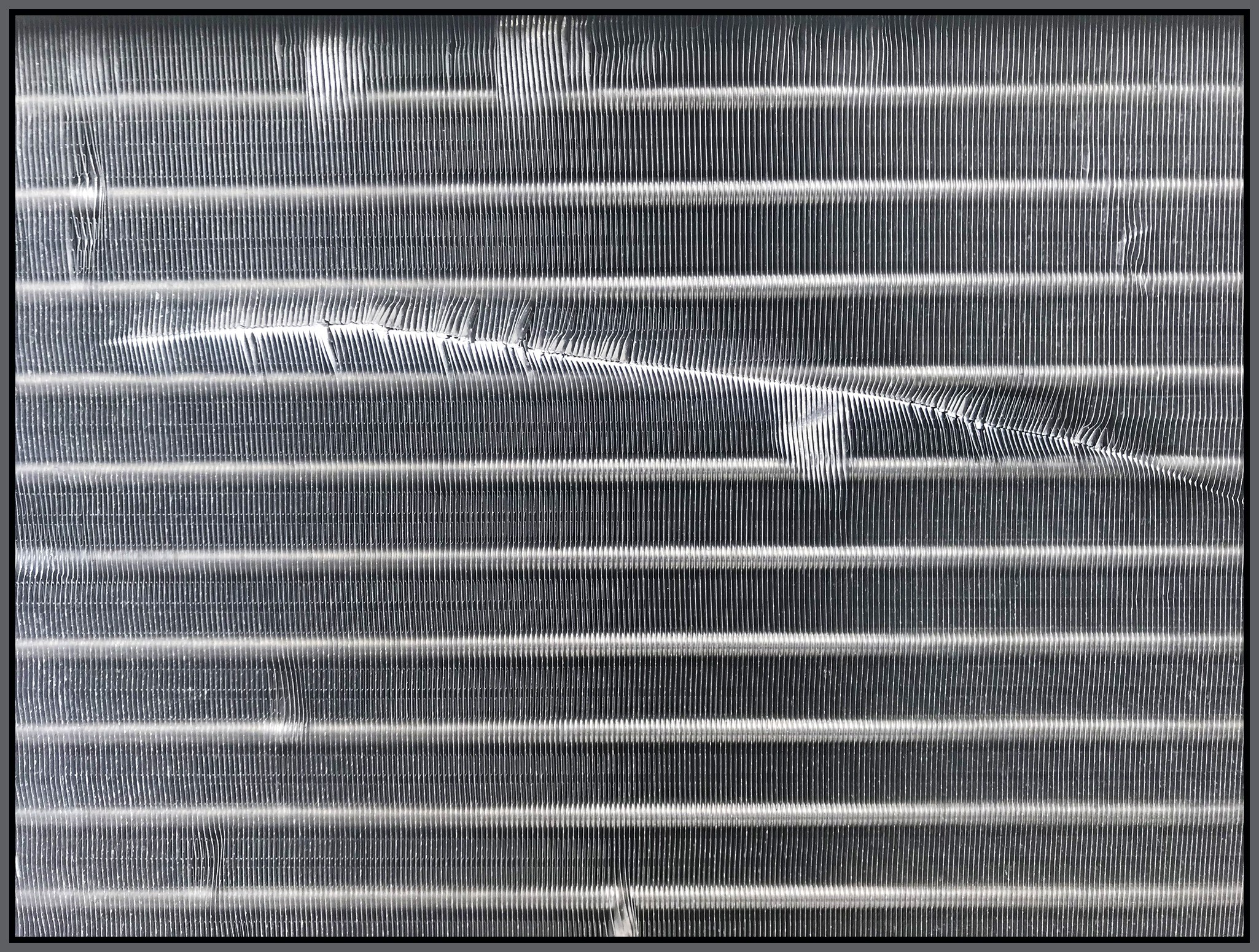

Sughra Raza. Light As a Feather. Boston, Sept 2020.

By the beginning of the 20th century, it had become clear to an influential minority of philosophers that something was badly amiss with modern philosophy. (There had been gripes of innumerable sorts since the beginning of modernity in the 17th century; but our subject today is the present.) “Modern” here means something like “Lockean and/or Cartesian,” where this means … well, it’s not immediately clear what exactly this means, nor what exactly is wrong with it, and therein lies the tale of a good deal of 20th-century philosophy. As with every broken thing, we have two choices: fix it, or throw it out and get a new one; and many philosophers have advertised their projects as doing one or the other. However, as we might expect, unclarity about the old results in corresponding unclarity about the supposedly better new. What’s the actual difference, philosophically speaking, between rehabilitation and replacement?

By the beginning of the 20th century, it had become clear to an influential minority of philosophers that something was badly amiss with modern philosophy. (There had been gripes of innumerable sorts since the beginning of modernity in the 17th century; but our subject today is the present.) “Modern” here means something like “Lockean and/or Cartesian,” where this means … well, it’s not immediately clear what exactly this means, nor what exactly is wrong with it, and therein lies the tale of a good deal of 20th-century philosophy. As with every broken thing, we have two choices: fix it, or throw it out and get a new one; and many philosophers have advertised their projects as doing one or the other. However, as we might expect, unclarity about the old results in corresponding unclarity about the supposedly better new. What’s the actual difference, philosophically speaking, between rehabilitation and replacement? Over the course of two days in early September, the Trump administration quietly formalized its commitment to the ideology of white supremacy within the context of schooling and public education. In two separate but parallel moves, both of which would have made Senator Joe McCarthy proud, Trump announced that the Department of Education (DOE) would investigate public schools to determine if they were using the Pulitzer-Prize winning curriculum, The

Over the course of two days in early September, the Trump administration quietly formalized its commitment to the ideology of white supremacy within the context of schooling and public education. In two separate but parallel moves, both of which would have made Senator Joe McCarthy proud, Trump announced that the Department of Education (DOE) would investigate public schools to determine if they were using the Pulitzer-Prize winning curriculum, The

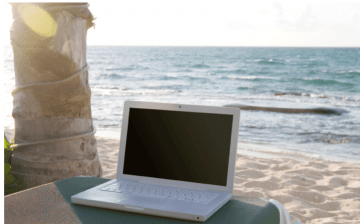

I’ve telecommuted from home for many years now. Before COVID-19, I would rarely turn my camera on when I was on video chats. And if I did, I’d make sure to put makeup on and look somewhat professional and put together from at least the waist up. But since lockdown started in March, I now turn my camera on for almost every video call and I don’t bother to put makeup on or to change my clothes from whatever ratty t-shirt I happen to be wearing. And I don’t care. I sit in my armchair au natural, secure in the knowledge that everyone I’m on calls with is likely dressed casually and taking the call from some room in their home. We’ve seen each other badly in need of haircuts. Then, in some cases, with bad haircuts that we did ourselves or let family members do to us. And we’ve grown familiar with each other’s living spaces, pets, and sometimes family members. I know the view outside of one colleague’s window, the clock on the wall behind another and I always admire the piece of art behind my colleague in Austin. Except for the occasional vacation house rental for a week or two, we’ve all been working out of our homes, living a more lockdown, limited version of the work-life we lived before. It made sense to stay put while lockdown was at its peak. But as it eases up, at least in some places, and while its clear that office life isn’t going back to normal anytime soon, is there a different, new way to live and work?

I’ve telecommuted from home for many years now. Before COVID-19, I would rarely turn my camera on when I was on video chats. And if I did, I’d make sure to put makeup on and look somewhat professional and put together from at least the waist up. But since lockdown started in March, I now turn my camera on for almost every video call and I don’t bother to put makeup on or to change my clothes from whatever ratty t-shirt I happen to be wearing. And I don’t care. I sit in my armchair au natural, secure in the knowledge that everyone I’m on calls with is likely dressed casually and taking the call from some room in their home. We’ve seen each other badly in need of haircuts. Then, in some cases, with bad haircuts that we did ourselves or let family members do to us. And we’ve grown familiar with each other’s living spaces, pets, and sometimes family members. I know the view outside of one colleague’s window, the clock on the wall behind another and I always admire the piece of art behind my colleague in Austin. Except for the occasional vacation house rental for a week or two, we’ve all been working out of our homes, living a more lockdown, limited version of the work-life we lived before. It made sense to stay put while lockdown was at its peak. But as it eases up, at least in some places, and while its clear that office life isn’t going back to normal anytime soon, is there a different, new way to live and work?

We are not dead yet. Battered a little, yes. Frustrated, anxious, wondering about our jobs, our neighborhoods, our schools, absolutely. Definitely not dead.

We are not dead yet. Battered a little, yes. Frustrated, anxious, wondering about our jobs, our neighborhoods, our schools, absolutely. Definitely not dead.

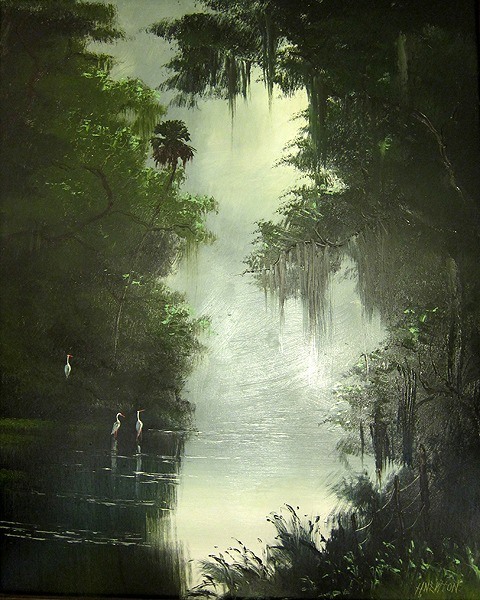

Harold Newton. Untitled, 1960s.

Harold Newton. Untitled, 1960s.