by Leanne Ogasawara

I’d been living in Tokyo about ten years, when a friend’s father decided to perform a little experiment on me. Arriving one cool autumn evening at their home in suburban Mejirodai, he waved my friend away, telling her: “I want to have a little chat with Leanne.” Sitting down on the sofa across from him, he poured me a cup of tea. In truth, I can’t recall what we chatted about, but about twenty minutes into the conversation, he suddenly clasped his hand together in delight–with what could only be described as a childlike gleam in his eyes– and said, “Don’t you hear something?”

I’d been living in Tokyo about ten years, when a friend’s father decided to perform a little experiment on me. Arriving one cool autumn evening at their home in suburban Mejirodai, he waved my friend away, telling her: “I want to have a little chat with Leanne.” Sitting down on the sofa across from him, he poured me a cup of tea. In truth, I can’t recall what we chatted about, but about twenty minutes into the conversation, he suddenly clasped his hand together in delight–with what could only be described as a childlike gleam in his eyes– and said, “Don’t you hear something?”

I was puzzled by this sudden turn of events. I sat quietly for a moment, listening– and then shook my head, no.

He was incredulous (but I couldn’t help but feel he also looked quite pleased with himself) and said: “Are you telling me that you have noticed nothing unusual here this evening?” He cupped his hand around his right ear as if making to try and hear a faint sound.

When I shook my head again, he giddily pulled out a small bamboo cage from under his chair. I immediately realized that he had a bell cricket in there. In fact, the cricket was chirping quite loudly!

How on earth had I missed it?

Seeing my look of distress, he excitedly explained that Japanese people process the sound of insects using the same side of their brain as they do language –while foreigners (he looked at me pointedly) process it on the other side of the brain, as a kind of background noise. He wondered if the sound didn’t actually annoy me? Japanese people, he said, hear the sound of singing crickets as music. He then told me about a recent academic paper that had been published on this very subject (he was, after all, a scientist). Here is a more recent such paper. My friend Chieko had come downstairs by this time and was listening to all this from the corner of the room, rolling her eyes dramatically.

What could I say? I simply didn’t “hear” it.

It is true that in English we don’t really have the vocabulary available in Japanese to evoke the ringing, chirping and clicking sounds of all the autumnal “insects voices” (虫の声). We also don’t really have common expressions for our human reactions to the chorus of insects (虫の合唱), the crying of the bell crickets (鈴虫が鳴く), the cicada rains (蝉しぐれ) etc, etc… My friend’s father ended his experiment, wondering if I lived long enough in Japan, if I wouldn’t someday be able to really hear the beauty of the autumn insects or appreciate the rain-like sound of the cicadas in summer.

I wondered too. And worried.

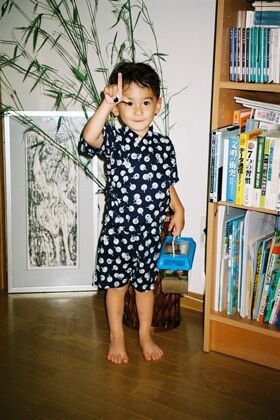

So, I didn’t take any chances when my son was born. As soon as he was old enough, I readily agreed to his request to get a pet bell cricket. Oh, how he loved it and carried it around happily all over our apartment. At night, he would place the little cage next to him as he crawled into our futon. He told me how he loved falling asleep to its singing. I just hope he doesn’t remember when I “accidentally” killed his pet after it got loose in the apartment –and I thought it was a cockroach… Ooops!

The truth is, despite what happened that day at my friend’s home in Mejirodai, I had loved the sound of the crickets long before I ever went to Japan. As a a child in Los Angeles, I used to always want to keep my windows open on warm night to listen to peaceful sound of the sprinklers and hear the crickets in the grass out back. We even sometimes could hear frogs back there! With several species of singing insects, their song rivaled the music I would later hear in Japan!

2.

But what happened to those crickets anyway?

Not only do I distinctly remember the chorus of crickets, but there were also armies of ants. We had flies that were so pesty we kept swatters out all summer. We also avoided eating outside on warm nights because of the way they swarmed. Bees too. I remember frogs and uncountable numbers of worms and snails. Fast forward forty years. Now, living in Pasadena, I kept wondering about this to my husband: “Don’t you remember swarms of gnats and flies forever buzzing around you? And the bugs we used to get in our eyes bicycling around town as kids?” He said it was the same in Ohio. And there were mosquitoes too. It felt so strange like no one noticed that an army of bugs had disappeared completely.

Then last fall the articles began appearing. The first one to really grab people’s attention was in the New York Times Magazine last November, called The Insect Apocalypse is Here. The title says it all. But reading it, I was floored for it was much worse than I thought. How is this possible that we are currently witnessing a mass extinction– an event so rare that it has only happened five times prior in the history of life on earth? More scary still to be fully aware that not only are witnessing it but that we are causing it? I feel a terrible loss whenever I hear a cricket in Pasadena now; for it is always just one lone cricket. Compared to the multitude of cricket voices I recalled from my childhood, their plaintive, lonely voices sound so sad to me now. Scientists say we are currently losing species at thousands of times the natural background rate of extinction, with literally dozens going extinct every day.

I recently read that a philosopher coined a new term for the sense of loss we feel in the face of climate change and animal extinction. Of course, there is a medical word –now officially validated by the American Psychological Association to be used as a clinical diagnosis, called “eco-anxiety,” but Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht wanted a word to express the sense of sadness and loss that is affecting us as well.“Solastalgia” is the word he came up with. Composed of three elements: solas, from the Latin root for comfort in the face of distress and the Greek root algia for pain.

The word is consciously meant to bring to mind another word, nostalgia–but “solastalgia” is less related to a particular place as it is to what is missing from this place. This new word is not about looking back to some golden past, nor is it about seeking another place as “home.” It instead points to the “lived experience” of the loss of the present as manifest in a feeling of dislocation; of being undermined by forces that destroy the potential for solace to be derived from the present. In short, solastalgia is a form of homesickness one gets when one is still at “home.” And indeed, the article The Insect Apocalypse is Here, begins with descriptions of “loss”, “nostalgia,” “noticing,” and “missing” experienced by citizen scientists who were inspired by their feelings to get out there and figure out where the insects had gone.

Reading this, I wondered if the Portuguese term, saudade is not the word we really need here? Often claimed to be untranslatable into English, it is saudade that so poignantly infuses Portuguese fado music and captures that feeling of profound melancholic longing for someone or something that is missing. I read once that saudade is the love that remains when the thing itself is gone. This longing and lamenting for what is gone forever? I think of it as a quiet tightening in the chest or that feeling of loss that hurts your stomach. I experience a physical pain in my heart every time I hear a lone cricket singing outside. Or if see a pair of butterflies out on my walk, my heart leaps.

Missingness. Longing and nostalgia for the missing soundscape of buzzing bees and swarming flies, of singing insects and frogs!

3.

According to the traditional calendar of East Asia, we are about to enter into a period of time known as “Insects Awaken (啓蟄).” The ancient Chinese calendar is a lunar-solar calendar. With months based on the phases of the moon (each month began with the new moon), the seasons were kept track of by observing the movement of the sun against 24 solar points, called “the twenty-four sekki” ( 24節気). With lyrical names that have been delighting people in that part of the world since ancient times, each sekki is expressive of the seasonal phenomena traditionally associated with that time of year. But, it should be kept in mind that these were expressive of the seasonal phenomena happening at that particular time of year around the Yellow River Basin area in China, and so didn’t necessarily hold perfectly true for other places where the calendar was in use– for example, in Japan, Korea, Vietnam and southern China. For example in a tropical place like Vietnam, which never sees frost much less snow, once celebrated festivals occurring during the “Time of Lesser Snow.” Of the twenty four seasonal names, only one is named after a phenomenon associated with insects–this time of insects awakening. Around March 6, the sun reaches 345 degree right ascension and we enter the time of “Insects Awaken 啓蟄 . In the old days, people thought that the awakening insects brought about the sound of loud thunder, also associated with this time of year. That is to say, the return of the insects after the long quiet winter was a big deal.

Having a calendar that marks the seasonal events not only helps you feel more connected to the rhythms of nature but it is an aid to noticing. Incidentally, the 24 sekki are further divided into 72 microseasons, called the 72 ko (72候). There is a wonderful app you can download to your phone to follow along. I keep threatening to create my own 72 ko specific to LA. But will insects be part of it? Believe it or not, there is also a cricket in a cage iPhone app, called 虫かご. Sad to imagine that this is all we might be left with when all the music has stopped.

++

My post on climate change and the sound of lotus blossoming

My post on nostalgia for dark skies filled with stars

The Japanese Calendar/ App of 72 Micro Seasons

Books: Bug Music, by David Rothenberg; Cricket Radio, by John Himmelman; Sixth Extinction, by Elizabeth Kolbert

Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Migration –for a novel that illuminates what it is like NOW to be witnessing extinction