I don’t know what Damien Chazelle was thinking as he was crafting First Man, a film about Neil Armstrong and his moon landing in Apollo 11, but to create the film we saw he had to “cleanse” it of four decades of space-adventure films. “But why,” you might ask, “would he want to do that? What’s wrong with adventures in space?” Nothing, if that’s your cup of tea. But, on the evidence of the film itself, he had something else in mind.

“What, pray tell, was that?” you ask. Let’s take a look.

The film opens on Neil Armstrong in a test flight of an airplane. While we do have some shots of the plane from the outside and at a distance, most of the shots are of the plane’s cockpit, either from Armstrong’s point-of-view has he looks about the cockpit, often at his hands activating controls, or through the window at the sky. There’s trouble, the image vibrates, a reflection of the plane’s motions. We hear voices (I think). We know Armstrong’s going to pull out of it because, well, after all, he did go to the moon and that’s not yet happened. There’s a strong sense of being enclosed, being trapped, of being at the edge of desperation.

No sense of wide open spaces, no wild blue yonder. Just white knuckles holding on and deliberate self-mastery. Keep it together. Pull through. And then it’s over. Armstrong lands the plane and gets out.

The aerial adventure trope has been held at bay. We’ve been told, “this is not that kind of film.” And the film makes a quick shift to a different register.

We move into Armstrong’s home. His young daughter, Karen, has cancer. And that’s what we see, Armstrong and his wife Janet caring for Karen. Intensely domestic. To the hospital for radiation treatments. And then we hear the sound of a winch lowering a small casket into a grave. We see Armstrong, his wife, and son at the funeral.

And then it’s over. The film moves to yet another register. We see Armstrong at work, in his office. His boss offers him time off, which he declines. He wants/needs to work. He scans his desktop, see a NASA newsletter with a story about the Gemini program. He decides to apply. Was that decision a response to, a way of coping with, his daughter’s death? Who knows. Armstrong doesn’t say that he’s applying to Gemini because his daughter has died. He says nothing at all about why he applied. He just does.

But the film creates a connection by virtue of its narrative strategy. First we see a dicey test flight. And then we cut to Karen’s illness. No causal connection is asserted or implied there, nor would I think that anyone infers cause. All we have is sequence, juxtaposition. Within the imaginative space that is First Man, that’s what we’ve got. Two things first: a test flight, a death in the family. And then a third: Armstrong applies to the Gemini program, an orbital program that preceded the Apollo moonshots.

And so it goes for the rest of the film. We see astronaut training, early space flights, a Soviet success, a disastrous launch-pad failure, but also a move to Houston, Janet is pregnant, now they have two sons, and so on. The film weaves back and forth between domestic life astronaut life.

Just before Armstrong is to go to the moon these two strands come together. He’s packing his bags and apparently hopes to slip out of the house without talking to his sons. Janet won’t allow this. She knows that he might not return, as does he, and she wants him to acknowledge that to his sons. He talks with them and acknowledges that, yes, he might not return.

Then we move to the launch pad and to the moon. Armstrong steps out onto the lunar surface, utters the famous line – “That’s one small step for [a] man; one giant leap for mankind” – and sets out walking. What’s the last thing we see Armstrong do on the moon? He drops Karen’s identity bracelet into a crater. That action explicitly asserts a connection between his daughter’s death and his decision to enter the astronaut program. That connection is how this film asserts the sacred quality of walking on the moon. The next shot has him safely back on earth. Then he’s in quarantine, where he meets his wife. They cannot touch, directly, but they touch the window separating them in the same spot. No talk. The film ends.

Does Armstrong tell anyone about leaving Karen’s bracelet on the moon? Who knows? We do.

* * * * *

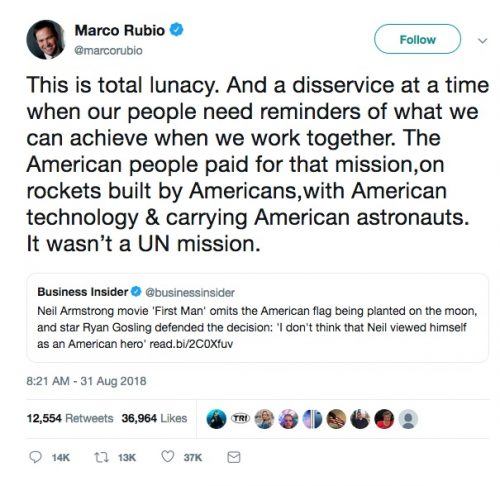

While the film does show the American flag on the moon, it didn’t show Armstrong actually planting the flag on the moon. And that caused a bit of a ruckus. For example:

Chazelle offered this statement:

In “First Man” I show the American flag standing on the lunar surface, but the flag being physically planted into the surface is one of several moments of the Apollo 11 lunar EVA that I chose not to focus upon. To address the question of whether this was a political statement, the answer is no. My goal with this movie was to share with audiences the unseen, unknown aspects of America’s mission to the moon — particularly Neil Armstrong’s personal saga and what he may have been thinking and feeling during those famous few hours.

I wanted the primary focus in that scene to be on Neil’s solitary moments on the moon — his point of view as he first exited the LEM, his time spent at Little West Crater, the memories that may have crossed his mind during his lunar EVA. This was a feat beyond imagination; it was truly a giant leap for mankind. This film is about one of the most extraordinary accomplishments not only in American history, but in human history. My hope is that by digging under the surface and humanizing the icon, we can better understand just how difficult, audacious and heroic this moment really was.

Thus have gave us the statement of universality – “one giant leap for mankind” – and the personal statement of mourning and healing, the bracelet. But he sidestepped nationalist sentiment.

To humanize the icon: to endow it with a sense of the sacred?