by Jackson Arn

Slurs have a way of mellowing into labels. History is full of Yankees and Cockneys, Methodists and Jesuits, Whigs and Tories, who steal a term of abuse and apply it to themselves as an act of sardonic revenge. Sometimes the tactic works too well, and people forget that the word was ever tainted. And sometimes the definition changes so many times people lose count, and the word is left to drag a muddle of meanings behind it.

“System” is such a word. Its DNA is full of recessive genes ready to reappear in the next generation. It suggests the banal and the sinister equally, a low, humming scientism and a hiss of danger. Politicians use it with both connotations in mind, sometimes both at once. Immigrants, trans activists, thwarted unionists are advised to have faith in the system, even as other politicians mock them for gaming it—can the two systems really be the same? Political science majors, not yet disillusioned, dream about the day they’ll change the system from within. In 1969, Bill Clinton, 23 years old and already impatiently waiting to be president, wrote, “I decided to accept the draft in spite of my beliefs for one reason: to maintain my political viability within the system.” Today, everyone seems to agree that the system, whatever it might be, is rigged. The word’s ambiguity is its longevity.

From the Greek: sun, meaning “with,” and histanal, meaning “set up, stand”—thus, a whole made out of parts, standing together. Which parts, and why they stand together, is left unclear—an ambiguity the rest of the sentence is supposed to correct but rarely does. This ambiguity is a part of the modern condition, since modernity depends on systems. Systems, rather than deities or monarchs, keep us safe: systems, for which individual parts are important but never all-important; systems, whose purpose, by definition, cannot be found in any single one of these parts.

Modernity is supposed to be an age of science, and the recent history of science is largely a history of systems. The word is already there, waiting for someone to connect the pieces: 1543, the solar system; 1628, the circulatory system; 1900, the nervous system; 1902, the endocrine system; 1956, the earliest mention of computer systems. In 1962, a NASA technician became the first person to say, “All systems go,” which isn’t a bad description of modernity itself. Read more »

It’s dawned on me, looking at recent (and not so recent) commentary on Shakespeare, that a wedge is being driven between the Bard and the culture in which he lived. Although I haven’t actually heard the following syllogism, it seems to be lurking behind much current criticism:

It’s dawned on me, looking at recent (and not so recent) commentary on Shakespeare, that a wedge is being driven between the Bard and the culture in which he lived. Although I haven’t actually heard the following syllogism, it seems to be lurking behind much current criticism:

![Shakespeare & Company, Paris. [Wikipedia]](https://3quarksdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/SandC.jpg)

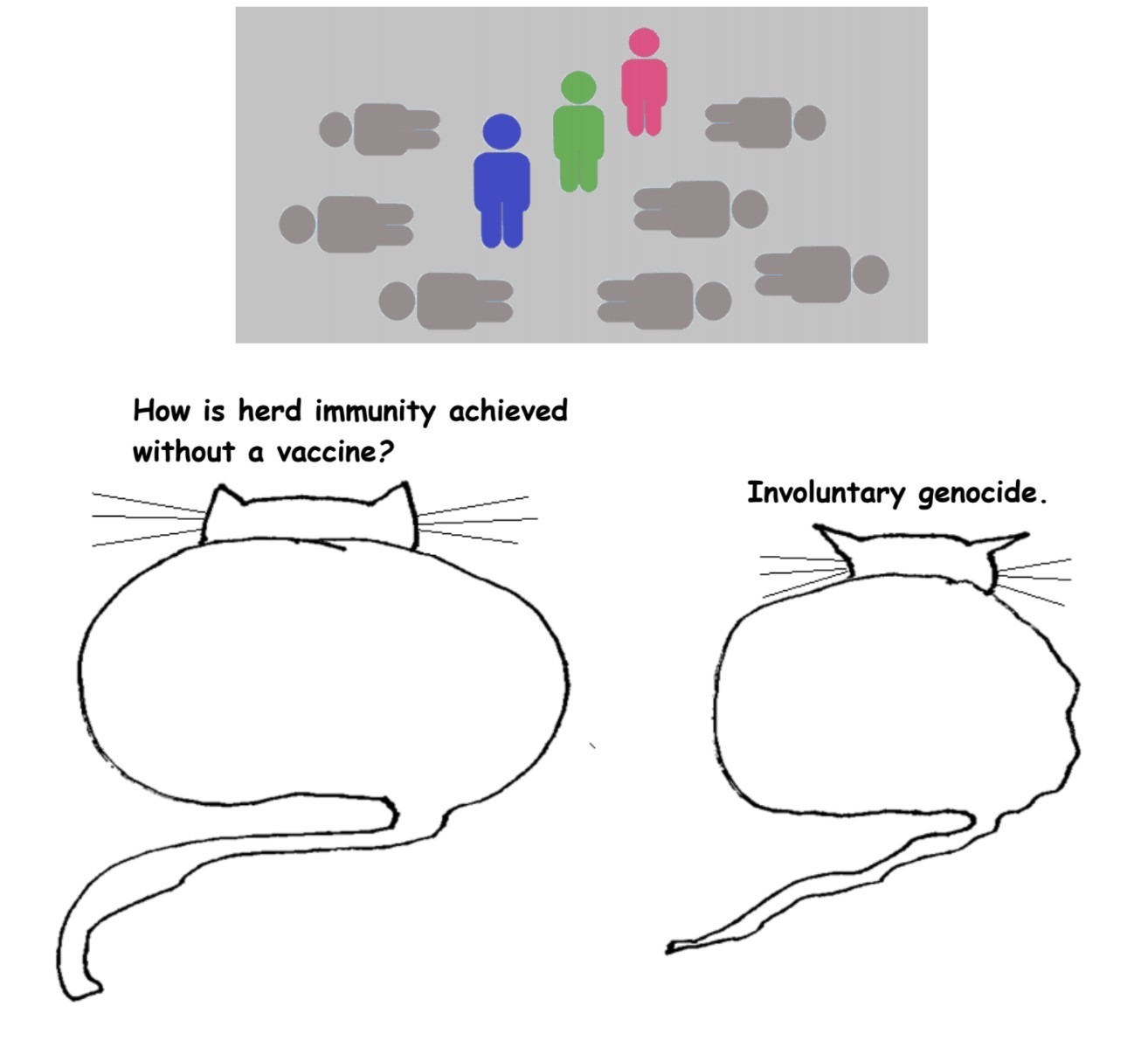

Racial disparities are present in all aspects of life. In the U.S.

Racial disparities are present in all aspects of life. In the U.S.  Some people whose political views are liberal and progressive say they will not vote in the 2020 US election. They detest Donald Trump and his Republican enablers like senate leader Mitch McConnell; they oppose Trump’s policies on most issues–the environment, immigration, health care, voting rights, police brutality, gun control, etc.; but they still say they won’t vote. Why not?

Some people whose political views are liberal and progressive say they will not vote in the 2020 US election. They detest Donald Trump and his Republican enablers like senate leader Mitch McConnell; they oppose Trump’s policies on most issues–the environment, immigration, health care, voting rights, police brutality, gun control, etc.; but they still say they won’t vote. Why not?

Last month’s most popular movie on Netflix is a horror show in the guise of a documentary. In 2020, reality has turned scarier than fiction, and The Social Dilemma expends more dread per minute than any episode of Black Mirror. It’s a timely, manipulative film, built for one purpose: to scare the f*ck out of everyday Americans.

Last month’s most popular movie on Netflix is a horror show in the guise of a documentary. In 2020, reality has turned scarier than fiction, and The Social Dilemma expends more dread per minute than any episode of Black Mirror. It’s a timely, manipulative film, built for one purpose: to scare the f*ck out of everyday Americans.