by Akim Reinhardt

In early August of 2000, I made my way from Lincoln, Nebraska to Tempe, Arizona. I had recently completed my Ph.D. and was hustling off to begin work as a post-doc at Arizona State University. Everything I owned, including two cats, was jam packed into a red Ford Escort station wagon. As I zig-zagged my way from the Great Plains to the Southwest, I allowed the felines to roam free through its cramped quarters.

That was my first mistake.

Poopster, the sweet gray and white female with tons of charm but not a whole lot upstairs, settled in nicely, nestling on the floor board near my feet. But Shango, the tiger with white socks who was the brains of their operation, freaked out. Somehow he managed to wedge himself underneath the driver’s seat.

My second mistake was letting him stay there.

He’s scared, I thought to myself. If he feels safe, just let him hunker down there. What harm could it do?

Never once did it occur to me that, at some point during this cross-country trip, he would have to relieve himself.

I had that car another three years, but despite my best efforts at detailing and perfuming, the smell never really went away. More than a year later, it was still bad enough that my girlfriend refused to drive with me from Philadelphia to Detroit to attend a wedding.

Funny though. The Colorado state trooper who pulled me over for speeding, when that urine was really fresh and pungent, didn’t seem to notice at all while he was writing me up.

I didn’t pay the ticket.

Fuck you, I thought to myself. I got enough fuckin’ problems.

I keept the windows down to mitigate the rancid smell of cat piss wafting through the vehicle as I wound my way down the eastern face of the Rocky Mountains.

To save money, I’d decided to camp. Having left Nebraska at a reasonable hour, I was already well into New Mexico on the other side of the Rockies by time I was ready to pull over for the night. I found a campsite in the middle of the desert along the Rio Grande River.

It sounds quite serene. A campsite in the desert along the Rio Grande.

In reality, it was crowded. Mostly families. I had imagined it would be relaxing and quiet, but the camp ground was more akin to a dusty KOA with kids running around and people watching TVs hooked up to generators.

I’d gone camping before, but never with the cats and never in the desert. The first obstacle was getting the tent pitched.

I had an actual pup tent, with a square bottom rising into a 6 foot-long triangle. Unlike modern tents, which use flexible poles to form a cris-crossing spine of that creates self-sustaining dome shape, a pup tent uses stakes, strings, and rigid poles. Its bottom four corners must be staked into the ground in order for it to rise.

That’s when I found out you can’t really drive metal stakes into the desert floor. I’d never been to the desert.

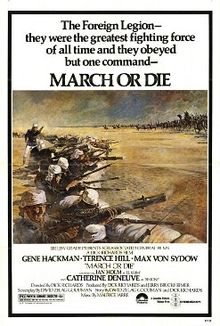

Actually, that’s not true. I’d been to El Paso a couple of years earlier. I always imagined the American desert would be something like a vast beach with cacti. But I guess you get either sand or a cactus, not both. Turns out the American Southwest doesn’t really have sand, or at least not the kind that sun worshipers lay their towels on, or that you see in old movies about the French Foreign Legion trudging through the Sahara. Mostly, it’s just a whole lotta dust and dry, hard, broken land. The landscape, desolate and rock strewn, reminded me of sections of the Bronx where buildings had been reduced to rubble.

The desert ground is goddamn hard. I bent a couple of stakes before realizing it wouldn’t work. So I improvised.

I gathered up several dozen rocks, and lined them along the perimeter of the tent. Now at least it wouldn’t blow away. The tent floor was secured to the ground. But how to actually pitch it?

I gathered up several dozen rocks, and lined them along the perimeter of the tent. Now at least it wouldn’t blow away. The tent floor was secured to the ground. But how to actually pitch it?

Raising an A-frame pup tent requires vertical poles to hold up the front and rear peaks. To keep those poles from falling down, long strings are tied to top of them and extend down to the ground in angled lines away from the tent. The strings are then staked to the ground to keep their lines taut. The tension on the staked strings keeps the poles erect, which in turn keep the tent raised and give it that classic A-frame shape.

But of course, I could not stake the strings into the ground. So instead, I simply planted the heaviest rocks I could find on top of the strings where they met the ground.

Sonofabitch. It kinda worked. Barely. Sorta. Not really. Just enough.

The strings popped loose a lot. And when a string slipped free from the rock that pinned it to the ground, the line would slacken completely and the pole would tip over, causing the tent to sag. Particularly when I went in or out of the tent, the front line would pop, the pole would lazily keel over, the front half of the tent would collapse, and I’d have to replant the string and reform the tent.

Enough was enough. Let’s just call it a night and hit the road in the morning.

I managed to get Shango and Poopster into the tent at dusk. Of course when I did, it collapsed. I went back out, propped the tent back up with the string-rock jerry rig, and gingerly made my way back in. Success.

As nighttime descended, the place quieted down. I made sure that all three zippers on the front of the tent were closed. Along the tent’s front triangle was a zipper that came all the way down the center of the triangle, from the peak to the ground. Two more zippers came across from the bottom corners, with all three of them meeting at the center-bottom point. Open them to leave through the flaps. Close them to secure yourself inside the tent. I checked. They were all closed.

Cats fed and watered, and sleeping bag laid out, the world was finally dark and calm. Tuckered out from a long drive, the stress of a speeding ticket that needed gaming, the logistics of a cross-country move on the cheap, and a cat urine fiasco that would never be defeated, I conked out.

Some time later, I don’t know when exactly, I awoke to the sound of a zipper being unzipped.

Laying supine with my head to the back of the tent, I raised up just enough to see the front of the tent, which sloped downward slightly. And there, framed by my two feet, toes pointed up, was Shango’s derriere. He had managed to unzip the front of the tent, or just enough of it to squeeze his head through the bottom center point where the three zippers met. Like a prisoner who’d spent years patiently digging a hole out of his cell with a spoon, he was tantalizingly close to making his escape. But the alarm was about to sound.

I immediately crouched forward and reached for him. However, before I could get my hands around him, he squirmed through the little opening he’d made for himself.

Motherfucker!

I lurched forward, unzipped the tent further, and scrambled buck naked into the cool desert night.

There’s always a moment. Whether it’s a dog, a horse, a cat, or whatnot. There’s that moment when the animal has begun to get away from you. Time slows to a crawl. You do the math in a fraction of a second. You never even passed algebra, but suddenly you’re calculating time-space vectors faster than a super computer. And just like that . . . you know. Either you can do this or you can’t. Either you can get this animal back with some desperate, lightening quick move, or it’s getting away from you.

I knew I still had a shot. Shango wasn’t much more than a body’s length out in front of me. If I leaped forward, stretching out completely, tearing and bruising my soft skin on the craggy desert floor, I could still reach him. And I loved that cat. Despite his pissing in the car, I love him.

I loved him more than Poopster even. He was the smart one. You can say that, cause they’re not kids. And the thought of him disappearing forever into the desert night was too much to bear. In that frozen moment, I knew what was still possible and never doubted what I needed to do.

I crouched, ready to spring.

And then, under the stars, upon that craggy lunar scape, something happened. Shango stopped. He looked around. He probably thought to himself, “Where in the fuck am I?”

Then he did a quick 180̊ and bolted through my legs, back into the partially collapsed tent.

I was thunderstruck. I couldn’t believe how lucky we both were. I turned around and crawled into the tent, not bothering to prop it back up. I zipped it closed, tied up the zippers, laid down, eased my breathing, and went back to sleep with my two cats safely secured in the half-standing pup tent.

The next morning while packing up the car to get the hell out of there, I lost Poopster.

I still don’t know how it happened. I could’ve sworn I’d put them straight from the tent into the carrier. But then suddenly she was gone.

I looked everywhere. All around the campsite, down by the banks of the Rio Grande, I asked other campers. Nothing. She had vanished.

After a half hour of looking, and the car fully packed, I sat there in the dust, leaning against the plastic, gray hub cap, tormented by images of her getting eaten by a coyote. She wasn’t very bright. She had no chance.

And then I heard a muffled meow. I quickly scrambled around the car and looked under it for the umpteenth time, but I didn’t see her. I heard it again. It was her for sure. The meow was close but distant at the same time. Where the fuck was she? I began meowing back to elicit her response, and kept honing in on the sound a little more each time. Then I figured it out. She wasn’t, was she? Could she?

I opened the car door, reached down, pulled the release, walked to the front of the car, and raised the hood. There she was, looking up at me from the engine block with eyes that did not match the wild sense of relief in mine.

I reached into the depths of my car engine, picked her up under the front legs, and brought her against my chest.

“I lied,” I told her. “I don’t love Shango more. I love you both just the same.”

Akim Reinhardt’s website is ThePublicProfessor.com