by Callum Watts

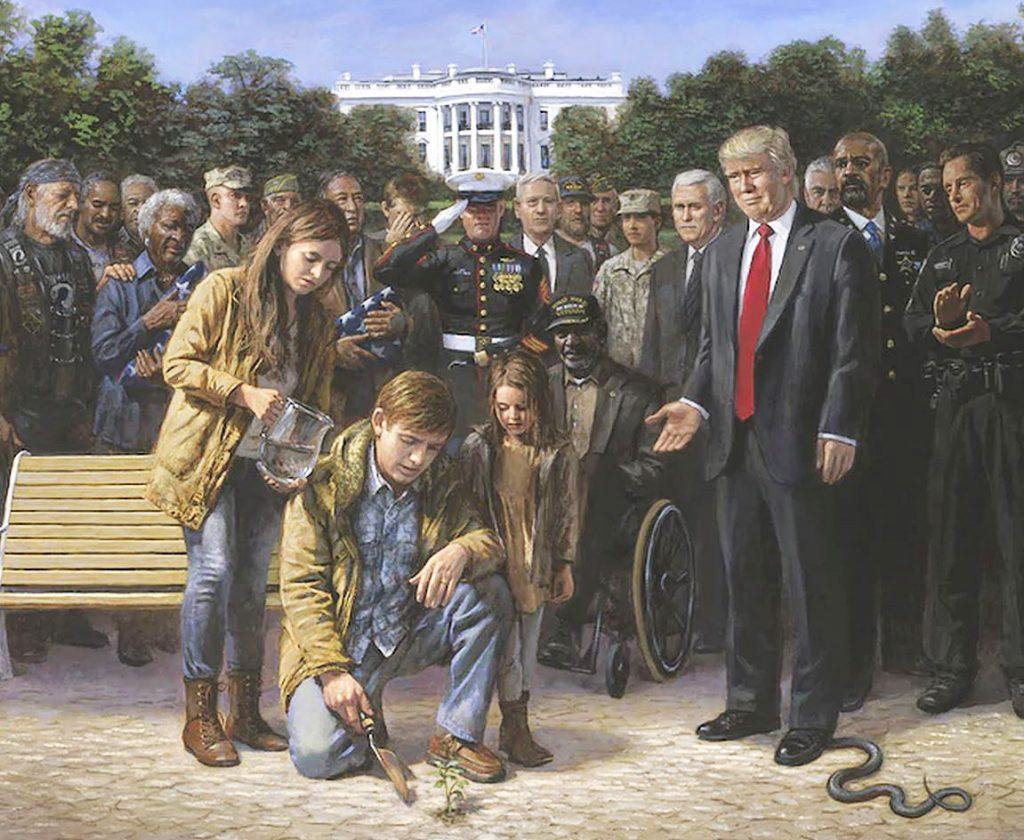

Picture this: a society that uses government controlled predictive mechanisms to determine the future of children before they get the chance to try and make something of themselves. In such a society exams and education play a secondary role, as predictive technologies are able to allocate the right people to the right tracks from the get-go. This might sound like Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, in which powerful social and biological engineering create and enforce social hierarchies. Every person has their place and role determined for them from early on.

Well this month, the UK almost followed suit, as hundreds of thousands of teenagers had their futures predicted, and grades assigned to them, not based on their performance in actual exams, but based on where they live and come from. In the context of the UK is highly correlated with seemingly irrelevant factors like wealth and race. These results were to be used to determine students’ futures. But rather than being rooted in a terrifying and highly sophisticated system for social control, the British version was driven by an obsession with efficiency and the limited understanding that an elite clique has of the value and purpose of education. Whilst the algorithm approach has now been abandoned, it’s interesting to examine what got us here.

On the face of it, the way we got into this mess looks like bad luck. The global pandemic made it difficult to sit exams safely, so a solution needed to be devised. By looking at a combination of teacher’s predictions, past individual performance, and past school performance, grades were generated for every high school student in the UK. But as soon as the grades started to come in, thousands of students and teachers were shocked to see bright students getting poor grades. How could it be that otherwise diligent and intelligent students from poor backgrounds were getting results which were demolishing their hopes and ambitions? Straightforwardly, it was because of the final variable in the prediction algorithm. By factoring in school performance, students were being downgraded not because of anything they had done, but quite literally because of where they come from. And roughly speaking, in the context of the UK, this means being judged based on wealth. The algorithm boosted the grades of the children of wealthy parents (on average) and reduced the grades of children from poorer backgrounds (on average).

The algorithm development was done by Ofqual, details here, and a PR firm was hired to defend and explain it to the public. The algorithm was roundly criticised as being inadequate and unfair even before it was used, and given its consequences, it seems pretty hard to defend now. But even if the algorithm had been perfect, the episode reveals a deeper unfairness within the education system as a whole. When I expressed my surprise at how brazenly this approach rewarded the wealthy to a friend who teaches in an inner-city school, she responded with frustration, pointing out that the algorithm mostly reflects what is already going on. Yes, this year would have been even crueller, because many talented children from disadvantaged backgrounds would have missed out on University places, but by and large access to the best universities is already unfairly distributed. The offending algorithm mostly replicated already existing inequalities. If it was shocking to see kids being allocated to universities by an algorithm that looks at their socio-economic background, then the whole educational system to date should shock us too. The algorithm merely made explicit the pre-existing injustice.

It’s worth pointing out that the objection is not to algorithms in public policy per se, an algorithm is just a formalisation of some decision or prioritisation procedure. It’s just that this particular decision procedure is patently unfair. This got me thinking about what a fair algorithm might look like. It seems that the measurable difference that a particular school or post code makes should not, in a fair system, be relevant to a child’s future. One can imagine an algorithm which was designed to remove this unfairness, basically the opposite of the government algorithm. The better the school, the less a high grade is worth, the worse the school, the more a low grade is worth. One challenge with this approach is that it would have the consequence of sending students who are less academically prepared onto courses which are no less demanding. This would create degree programmes where individuals would have different skill and knowledge levels in the subjects they were being admitted to study. You might wonder how someone would teach such a class. Would instructors be forced to lower either the quality or the difficulty of the material to avoid ‘leaving students behind’? This does not seem like a desirable outcome.

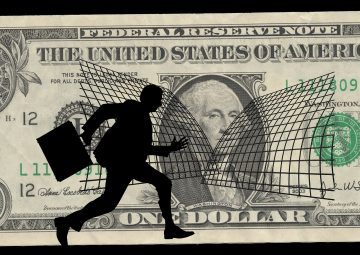

A university is supposed to produce graduates with a certain proficiency in their field of study. If the inputs are unsuitable, then the outputs will disappoint too. In some professional contexts this could lead to serious problems; we want properly qualified doctors, lawyers, nurses and so on. This model of education is connected to the idea that universities are a rigorous training ground, delivering people into adulthood so that they can go away and fulfil social roles to a certain standard. But when we look outside of the context of the professions which require specific technical skills, this way we measure whether this standard has been met is by looking at future earning power. And this is a model that UK society is to a greater or lesser extent bought into. Whether we’re employers, university administrators, or students, it’s that earning potential, that price tag which acts as the ultimate justification of an undergraduate education. We see this in how universities compete for students and in how the value of different courses are assessed. To give just one example, the University of the West of England announced plans to review whether it should have a philosophy programme. The key reason being that it does not perform well enough at creating highly employable graduates. This claim, aside from being demonstrably wrong based off of the Universities own statistics, clearly betrays an entirely jobs and market driven motivation for education.

There is a tendency to believe that this view of education is pragmatic, economically sound and the correct one to judge educational institutions by. But it misses many of the most important reasons we have an education. At an individual level personal edification and development, the pursuit of truth, beauty, and knowledge are all reasons someone might pursue higher education. And even at the level of society, we want more than individuals capable of becoming employees and employers. We want responsible members of communities, we want well informed citizens, we want people who behave ethically towards others, and we want to reproduce our traditions, knowledge and history into the future. We want to increase our stock of knowledge, scientific and otherwise, to become wiser and better at living together. This view, rather than seeing education as a conveyor belt to sort people into social roles, views education as key to human flourishing.

At first sight the flourishing view can appear indulgent, something that sounds nice but that we have neither the time nor resources for. But the more I’ve thought about it, the more convinced I am that it is the conveyor belt approach to education which is indulgent, and likely damaging to the long-term posterity of a society wedded to it. From a long-term perspective, both individually and collectively, the flourishing view is essential to the continued existence of communities in all times and places. It’s only in the context of a hyper competitive and highly unequal market society that the conveyor belt view becomes our chief frame of reference. And even then, its limitations are becoming clear. The social dysfunction created in winner take all economies seem to be exacerbated by this approach to education. The hyper specialisation and focus on grades seem to be having a devastating effect on mental health. This is mirrored in the way graduates are then tossed into a mode of living characterised by precarity and scraping together next month’s rent. And if we step back from the individual plight, we are confronted with a social situation in which individuals are finding it hard to organise themselves to solve anything but their own narrow sets of problems, and collective challenges go unaddressed.

The higher education system is not designed to produce individuals focussed on solving our collective challenges. And when it does produce such people, it is largely because individuals are taking it open themselves to try to swim against the current, in the face of overwhelming pressure to focus exclusively on employability. The powers that be are largely made up of privileged individuals for whom education really is a conveyor belt designed to deliver them straight to the levers of power. For them, these problems are not inherently connected to education because they don’t actually understand what the value of an education could be, because they understand it in the luxury context in which they received theirs. They see education as a finishing school for people whose destinies are essentially already fixed.

This is why when they looked at the fiasco unfolding with the exam’s algorithm, they were largely unable to see that anything very wrong with what was happening. Yes, some talented state school pupils might miss out on university places, but ultimately that would only affect a small number of individuals, and by and large the education system was still performing perfectly well in directing the right individuals to their allotted roles in the social and economic hierarchy. They don’t have the breadth of mind to understand that an education can and should do far more than this. Unfortunately, so trapped are we in the unpredictable currents of a competitive market economy, it feels impossible to look at education in this broader sense. But higher education does not exist to give people careers, flatter the egos of intellectuals, or to create employees. It exists to further knowledge, promote a society and culture worth living in, and to create citizens capable of being happy within it. This isn’t indulgent or fluffy or bourgeois. Along with family, it is the foundation of the ethical life which makes possible the long-term survival of a society.

researchers, as well. Indeed, Involve is an entire journal devoted to publishing new research in mathematics suitable for publication in mainstream research journals, but with the extra requirement that at least 1/3 of the authors be undergraduate students. Full disclosure: my colleague, Mike Jablonski, is an editor at the journal.

researchers, as well. Indeed, Involve is an entire journal devoted to publishing new research in mathematics suitable for publication in mainstream research journals, but with the extra requirement that at least 1/3 of the authors be undergraduate students. Full disclosure: my colleague, Mike Jablonski, is an editor at the journal.

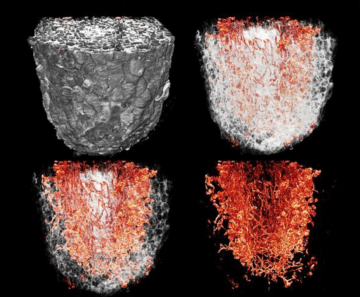

Louise Bourgeois

Louise Bourgeois

On January 28th of this year, just as the biggest

On January 28th of this year, just as the biggest  I majored in English in college.

I majored in English in college.

I came to

I came to

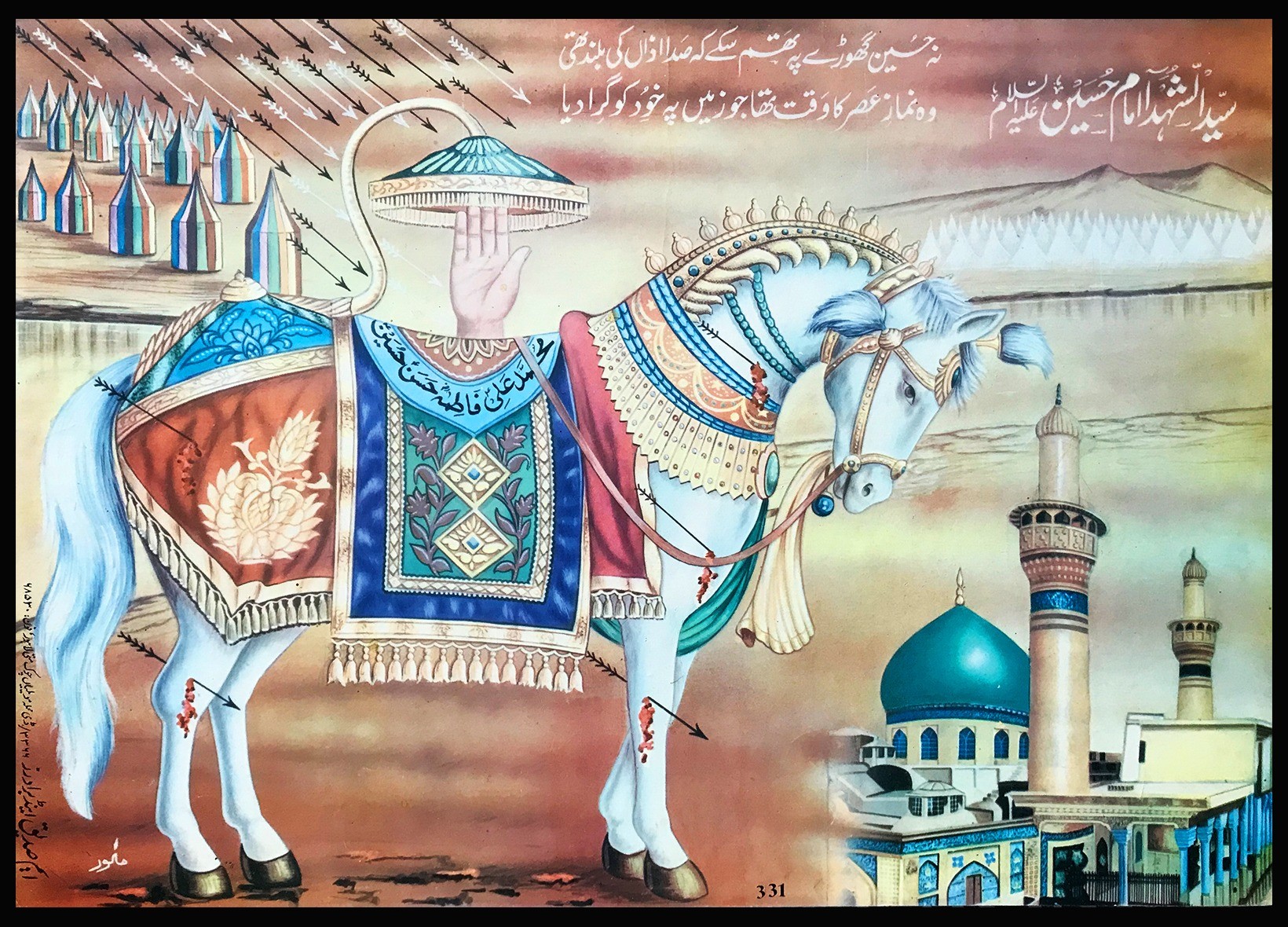

Unknown artist. Zuljanah (devotional folk art related to

Unknown artist. Zuljanah (devotional folk art related to