by Michael Liss

The Supreme Court doesn’t play politics.

The Supreme Court doesn’t play politics.

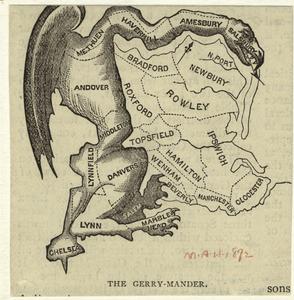

In what was destined to be an inevitable ruling, by an inevitable 5-4 vote, inevitably written by Chief Justice John Roberts, the Supreme Court decided, in Rucho v. Common Cause, that it couldn’t decide how much “partisan” gerrymandering was too much partisan gerrymandering. So it wouldn’t. Case closed.

Rucho is an extraordinary decision, with the potential, over the next 10 years, to change fundamentally the way we experience democracy. That may seem to be a radical statement, but it is absolutely true: Political parties now have a virtually free hand, once they obtain control over a state government, to redistrict as they see fit in order to retain that control. The Supreme Court is not completely out of the game—Roberts did acknowledge that they might still review gerrymandering based on race, or on “one-person, one-vote” grounds, but, by order of the Chief Justice, the Courts will be closed for a permanent federal holiday if the gerrymandering was done for the purpose of political gain.

This is an earthquake, which will, no doubt, lead to a further arms race between the parties. As Republicans control more states (Kyle Kondik, writing for Larry Sabato’s Crystal Ball, cites research indicating that Republicans control redistricting for 179 Congressional Districts, Democrats only 49), the advantage will be theirs. Many critics on the Left are suggesting that the conservative majority on the Court chose this path for precisely this reason. I prefer not to be cynical. Rather, I just want to point out the obvious: The real losers will be the center of the electorate; mainstream, moderate voters who find their concerns completely ignored because the more “safe seats” there are, the more influence primary voters (who tend to be far more doctrinaire) will have. This will inevitably lead to more radicalized government answerable to fewer and fewer people, and even more alienation. Read more »

The man for whom the word “Emergency” must have been invented (“serious, unexpected, and often dangerous situation requiring immediate action”) pulled the pin out of yet another hand grenade.

The man for whom the word “Emergency” must have been invented (“serious, unexpected, and often dangerous situation requiring immediate action”) pulled the pin out of yet another hand grenade.