by Jochen Szangolies

There seems to be a peculiar kind of compulsion among the philosophically minded to return, time and again, to the issue of free will. It’s like a sore on the gums of philosophy—one that might heal if only we could stop worrying it with our collective tongues. Such a wide-spread affliction surely deserves a fitting name: I propose Morsicatio Libertatum (ML), the uncontrollable urge to chew on freedom.

With the implicit irony duly appreciated, I am no exception to this rule: bouts of ML seize me, on occasion, while taking a shower, while walking through the woods, while pondering what to have for dinner. If I differ in any way from the typical afflicted, then it’s because deep down, I am not at all convinced that the issue really matters all that much. In most discussions of the problem of freedom, each camp seems so invested in their position that they consider a contravening argument not just erroneous, but nearly a point of moral offense. But ultimately, wherever the chips may fall, we can do nothing but live our lives as we do: whether by fate’s preordainment or by our own choices.

After all, it’s not like we consider things only worthwhile if their completion is, in some sense, up to us: the last chapter of the novel you’re reading, the last scene of the film you’re watching was completed long before you ever turned the first page or switched on the TV. Yet, there may be considerable enjoyment in witnessing its unfolding. Even more obviously, the tracks the rollercoaster rides are right there, for you to see—but that doesn’t take away the thrill.

But still, my aim here is not to examine the psychology of arguing over free will (as rewarding a topic as that might prove). Rather, I am writing due to a particularly fierce recent bout of ML, brought on by finding myself suspended 100m above the ground, climbing through the steel trusses of Germany’s highest railway bridge, and wondering whether I’d gotten myself into this, of if I could blame the boundary conditions of the universe. Thus, perhaps this essay should best be considered therapeutic (then again, perhaps that’s true of all philosophy). Read more »

When I was 12 my parents fought, and I stared at the blue lunar map on the wall of my room listening to Paul Simon’s “Slip Slidin’ Away” while their muffled shouts rose up the stairs. As I peered closely at the vast flat paper moon—Ocean Of Storms, Sea of Crises, Bay of Roughness—it swam, through my tears, into what I knew to be my future, one where I alone would be exiled to a cold new planet. But in fact it was just an argument, and my parents still live together—more or less happily—in that same house where I was raised.

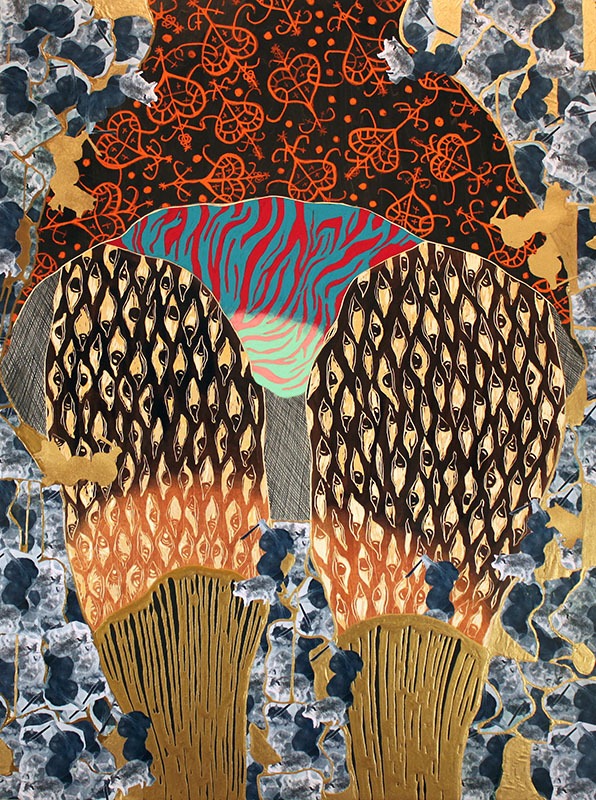

When I was 12 my parents fought, and I stared at the blue lunar map on the wall of my room listening to Paul Simon’s “Slip Slidin’ Away” while their muffled shouts rose up the stairs. As I peered closely at the vast flat paper moon—Ocean Of Storms, Sea of Crises, Bay of Roughness—it swam, through my tears, into what I knew to be my future, one where I alone would be exiled to a cold new planet. But in fact it was just an argument, and my parents still live together—more or less happily—in that same house where I was raised. Didier William. Ezili Toujours Konnen, 2015.

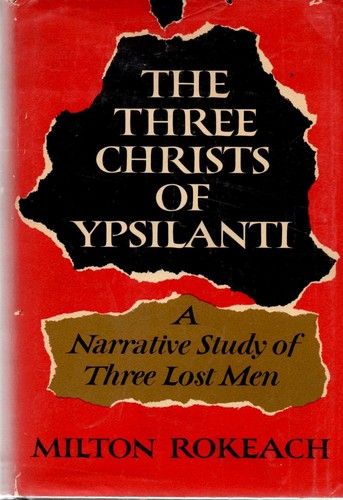

Didier William. Ezili Toujours Konnen, 2015. As an undergraduate History major, I reluctantly dug up a halfway natural science class to fulfill my college’s general education requirement. It was called Psychology as a Natural Science. However, the massive textbook assigned to us turned out to be chock full of interesting tidbits ranging from optical illusions to odd tales. One of the oddest was the story of Leon, Joseph, and Clyde: three men who each fervently believed he was Jesus Christ. The three originally did not know each other, but a social psychologist named Milton Rokeach brought them together for two years in an Ypsilanti, Michigan mental hospital to experiment on them. He later wrote a book titled The Three Christs of Ypsilanti.

As an undergraduate History major, I reluctantly dug up a halfway natural science class to fulfill my college’s general education requirement. It was called Psychology as a Natural Science. However, the massive textbook assigned to us turned out to be chock full of interesting tidbits ranging from optical illusions to odd tales. One of the oddest was the story of Leon, Joseph, and Clyde: three men who each fervently believed he was Jesus Christ. The three originally did not know each other, but a social psychologist named Milton Rokeach brought them together for two years in an Ypsilanti, Michigan mental hospital to experiment on them. He later wrote a book titled The Three Christs of Ypsilanti. “I am by nature too dull to comprehend the subtleties of the ancients; I cannot rely on my memory to retain for long what I have learned; and my style betrays its own lack of polish.”

“I am by nature too dull to comprehend the subtleties of the ancients; I cannot rely on my memory to retain for long what I have learned; and my style betrays its own lack of polish.”

On August 17, 1977, I stopped in as usual at our neighbors’ house, to while away the summer day with my younger brother and sister until our mother’s return home from the university. Our friends – two sets of twins and one singleton – were home-schooled by their mother, and we were all having a summer staycation in any case, so there was always somebody at their house, and a reliably lively time to be had. What met me when I walked into the kitchen that morning, however, was an unaccustomed stillness. All five young people were hovering around the door to the living room while their mother sat at the kitchen table, hunched over a newspaper. “Elvis is dead,” whispered the singleton. Presley had died the day before, in Memphis, in the early afternoon of August 16; but the headlines, and President Carter’s address, would be that day’s news, on the outskirts of Vancouver as elsewhere around the world.

On August 17, 1977, I stopped in as usual at our neighbors’ house, to while away the summer day with my younger brother and sister until our mother’s return home from the university. Our friends – two sets of twins and one singleton – were home-schooled by their mother, and we were all having a summer staycation in any case, so there was always somebody at their house, and a reliably lively time to be had. What met me when I walked into the kitchen that morning, however, was an unaccustomed stillness. All five young people were hovering around the door to the living room while their mother sat at the kitchen table, hunched over a newspaper. “Elvis is dead,” whispered the singleton. Presley had died the day before, in Memphis, in the early afternoon of August 16; but the headlines, and President Carter’s address, would be that day’s news, on the outskirts of Vancouver as elsewhere around the world.

The gully cricket I played in my neighborhood also had a tournament, where different neighborhoods of north Kolkata competed. I once played in such a tournament which was being held in the far north of the city, some distance from my own neighborhood. I don’t now remember the game, but I met there a savvy boy, somewhat older than me, who opened my eyes about Kolkata politics. When he asked me which locality I was from, he stopped me when I started answering with a geographic description. He was really interested in knowing which particular mafia leader my neighborhood fell under. Finding me rather ignorant, he went on to an elaborate explanation of how the whole city is divided up in different mafia fiefdoms, and their hierarchical network and different specialization in different income-earning sources, and their nexus with the hierarchy of political leaders as patrons at different levels. After he figured out the coordinates of my locality he told me which particular mafia don my neighborhood hoodlums (the local term is mastan) paid allegiance to. I recognized the name, this man’s family had a meat shop in the area.

The gully cricket I played in my neighborhood also had a tournament, where different neighborhoods of north Kolkata competed. I once played in such a tournament which was being held in the far north of the city, some distance from my own neighborhood. I don’t now remember the game, but I met there a savvy boy, somewhat older than me, who opened my eyes about Kolkata politics. When he asked me which locality I was from, he stopped me when I started answering with a geographic description. He was really interested in knowing which particular mafia leader my neighborhood fell under. Finding me rather ignorant, he went on to an elaborate explanation of how the whole city is divided up in different mafia fiefdoms, and their hierarchical network and different specialization in different income-earning sources, and their nexus with the hierarchy of political leaders as patrons at different levels. After he figured out the coordinates of my locality he told me which particular mafia don my neighborhood hoodlums (the local term is mastan) paid allegiance to. I recognized the name, this man’s family had a meat shop in the area.

On May 31st, 2021, I sent an email to John Pawelek, Senior Research Scientist at Yale University, requesting a zoom meeting. When a week went by without a response, I decided to call. Searching for his number, I came across his Obituary instead. John Pawelek died on May 31st, 2021. Alas, I missed my chance to speak to a knowledgeable and accomplished scientist.

On May 31st, 2021, I sent an email to John Pawelek, Senior Research Scientist at Yale University, requesting a zoom meeting. When a week went by without a response, I decided to call. Searching for his number, I came across his Obituary instead. John Pawelek died on May 31st, 2021. Alas, I missed my chance to speak to a knowledgeable and accomplished scientist. This year marks the 200th anniversary of Napoleon Bonaparte’s death in exile on the island of St Helena. And it was 206 years ago last June that his career came to a bloody end at Waterloo, with defeat at the hands of an allied army led by Britain’s Wellington and Prussia’s Blucher. But while the Emperor himself is dead and gone, the Napoleon Myth marches on, and is celebrated in some unlikely quarters.

This year marks the 200th anniversary of Napoleon Bonaparte’s death in exile on the island of St Helena. And it was 206 years ago last June that his career came to a bloody end at Waterloo, with defeat at the hands of an allied army led by Britain’s Wellington and Prussia’s Blucher. But while the Emperor himself is dead and gone, the Napoleon Myth marches on, and is celebrated in some unlikely quarters.