by Tamuira Reid

I.

I lost my father in August 2017. My son lost his a year later. I’ve always hated summer. Maybe because I was born on a cold January morning and I’ve got winter running through my blood. Maybe because the warm days always felt suffocating to me, in their endlessness. Maybe because it’s when everyone dies.

My father’s death was not a quick one off but a slow easy spread, permeating every organ, every passageway, every out he had left. Death teased him. Came at him hard then relented just long enough to make its presence known. To him. To us. To everyone at home who had their health still, dotting the hills of the small valley town around us. It pushed and pulled until every last hope for a dignified ending was filibustered. Until the man who had somehow managed to avoid hospitals for the better part of his life knew, very clearly, it would be the last place he’d see. One wall, three curtains, and a gurney. The daughters and the wife. The younger by not much brother who had already seen how this would play out because after all, cancer is no stranger in the branches of the Reid family tree.

The surgeon was wheeled into my father’s room – his concerned, televised face, skyping from a nearby trauma unit – to break the news. All systems a fail. Nothing more to be done.

I couldn’t help but think that if he were younger, they’d do more. Try harder. Not give up.

I told the nurses that the man in the bed bared no resemblance to our real father. Our real father still hiked and lifted weights and hauled timber without getting winded. Our real father could annihilate The Times Sunday crossword in under thirty minutes. Our real father read Huck Finn at eight years-old and Steinbeck at ten. Our real father could do anything they could, except save his own life.

But in the end, cancer is cruel. It’s ugly and thoughtless. And it couldn’t give two shits about who you might’ve been before it got there. Read more »

One remarkable redeeming feature of my dingy neighborhood in Kolkata was that within half a mile or so there was my historically distinctive school, and across the street from there was Presidency College, one of the very best undergraduate colleges in India at that time (my school and that College were actually part of the same institution for the first 37 years until 1854), adjacent was an intellectually vibrant coffeehouse, and the whole surrounding area had the largest book district of India—and as I grew up I made full use of all of these.

One remarkable redeeming feature of my dingy neighborhood in Kolkata was that within half a mile or so there was my historically distinctive school, and across the street from there was Presidency College, one of the very best undergraduate colleges in India at that time (my school and that College were actually part of the same institution for the first 37 years until 1854), adjacent was an intellectually vibrant coffeehouse, and the whole surrounding area had the largest book district of India—and as I grew up I made full use of all of these. Unlike her previous exhibit, James chose not to explicitly market

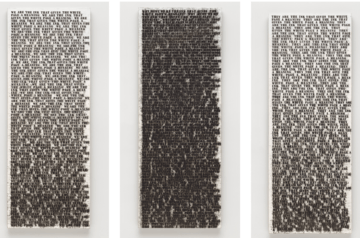

Unlike her previous exhibit, James chose not to explicitly market

The view that everyone who is capable has a basic duty to work and not be idle is the main tenet of what we call the work ethic. Closely related to this are two other ideas:

The view that everyone who is capable has a basic duty to work and not be idle is the main tenet of what we call the work ethic. Closely related to this are two other ideas:

When I was 12 my parents fought, and I stared at the blue lunar map on the wall of my room listening to Paul Simon’s “Slip Slidin’ Away” while their muffled shouts rose up the stairs. As I peered closely at the vast flat paper moon—Ocean Of Storms, Sea of Crises, Bay of Roughness—it swam, through my tears, into what I knew to be my future, one where I alone would be exiled to a cold new planet. But in fact it was just an argument, and my parents still live together—more or less happily—in that same house where I was raised.

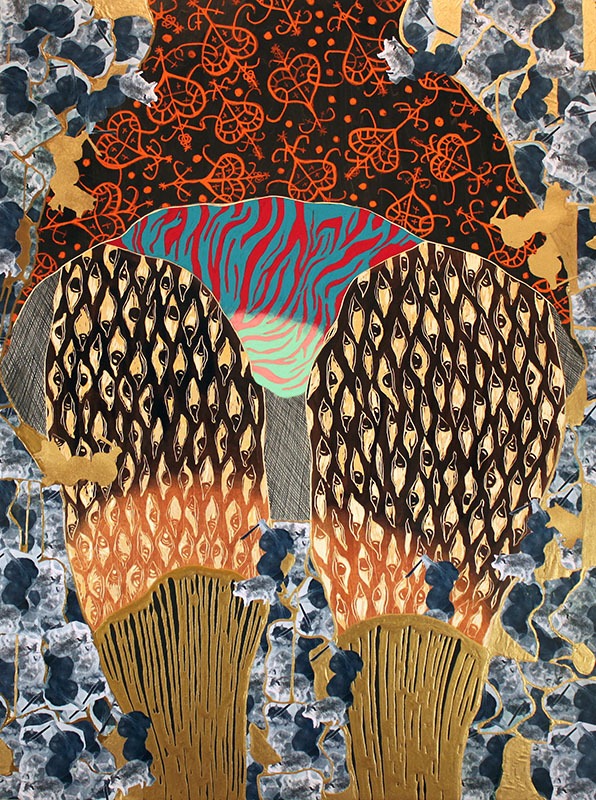

When I was 12 my parents fought, and I stared at the blue lunar map on the wall of my room listening to Paul Simon’s “Slip Slidin’ Away” while their muffled shouts rose up the stairs. As I peered closely at the vast flat paper moon—Ocean Of Storms, Sea of Crises, Bay of Roughness—it swam, through my tears, into what I knew to be my future, one where I alone would be exiled to a cold new planet. But in fact it was just an argument, and my parents still live together—more or less happily—in that same house where I was raised. Didier William. Ezili Toujours Konnen, 2015.

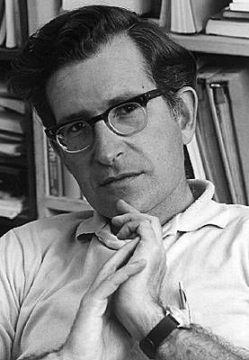

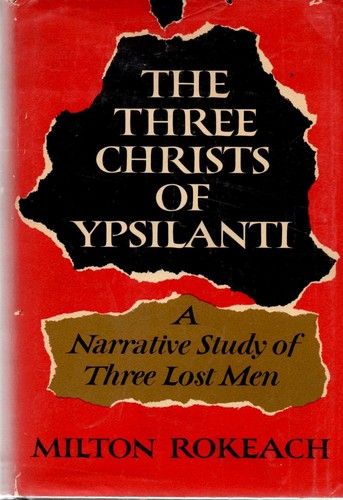

Didier William. Ezili Toujours Konnen, 2015. As an undergraduate History major, I reluctantly dug up a halfway natural science class to fulfill my college’s general education requirement. It was called Psychology as a Natural Science. However, the massive textbook assigned to us turned out to be chock full of interesting tidbits ranging from optical illusions to odd tales. One of the oddest was the story of Leon, Joseph, and Clyde: three men who each fervently believed he was Jesus Christ. The three originally did not know each other, but a social psychologist named Milton Rokeach brought them together for two years in an Ypsilanti, Michigan mental hospital to experiment on them. He later wrote a book titled The Three Christs of Ypsilanti.

As an undergraduate History major, I reluctantly dug up a halfway natural science class to fulfill my college’s general education requirement. It was called Psychology as a Natural Science. However, the massive textbook assigned to us turned out to be chock full of interesting tidbits ranging from optical illusions to odd tales. One of the oddest was the story of Leon, Joseph, and Clyde: three men who each fervently believed he was Jesus Christ. The three originally did not know each other, but a social psychologist named Milton Rokeach brought them together for two years in an Ypsilanti, Michigan mental hospital to experiment on them. He later wrote a book titled The Three Christs of Ypsilanti. “I am by nature too dull to comprehend the subtleties of the ancients; I cannot rely on my memory to retain for long what I have learned; and my style betrays its own lack of polish.”

“I am by nature too dull to comprehend the subtleties of the ancients; I cannot rely on my memory to retain for long what I have learned; and my style betrays its own lack of polish.”

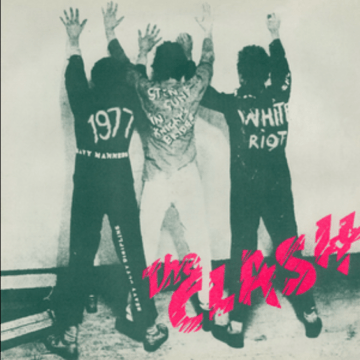

On August 17, 1977, I stopped in as usual at our neighbors’ house, to while away the summer day with my younger brother and sister until our mother’s return home from the university. Our friends – two sets of twins and one singleton – were home-schooled by their mother, and we were all having a summer staycation in any case, so there was always somebody at their house, and a reliably lively time to be had. What met me when I walked into the kitchen that morning, however, was an unaccustomed stillness. All five young people were hovering around the door to the living room while their mother sat at the kitchen table, hunched over a newspaper. “Elvis is dead,” whispered the singleton. Presley had died the day before, in Memphis, in the early afternoon of August 16; but the headlines, and President Carter’s address, would be that day’s news, on the outskirts of Vancouver as elsewhere around the world.

On August 17, 1977, I stopped in as usual at our neighbors’ house, to while away the summer day with my younger brother and sister until our mother’s return home from the university. Our friends – two sets of twins and one singleton – were home-schooled by their mother, and we were all having a summer staycation in any case, so there was always somebody at their house, and a reliably lively time to be had. What met me when I walked into the kitchen that morning, however, was an unaccustomed stillness. All five young people were hovering around the door to the living room while their mother sat at the kitchen table, hunched over a newspaper. “Elvis is dead,” whispered the singleton. Presley had died the day before, in Memphis, in the early afternoon of August 16; but the headlines, and President Carter’s address, would be that day’s news, on the outskirts of Vancouver as elsewhere around the world.