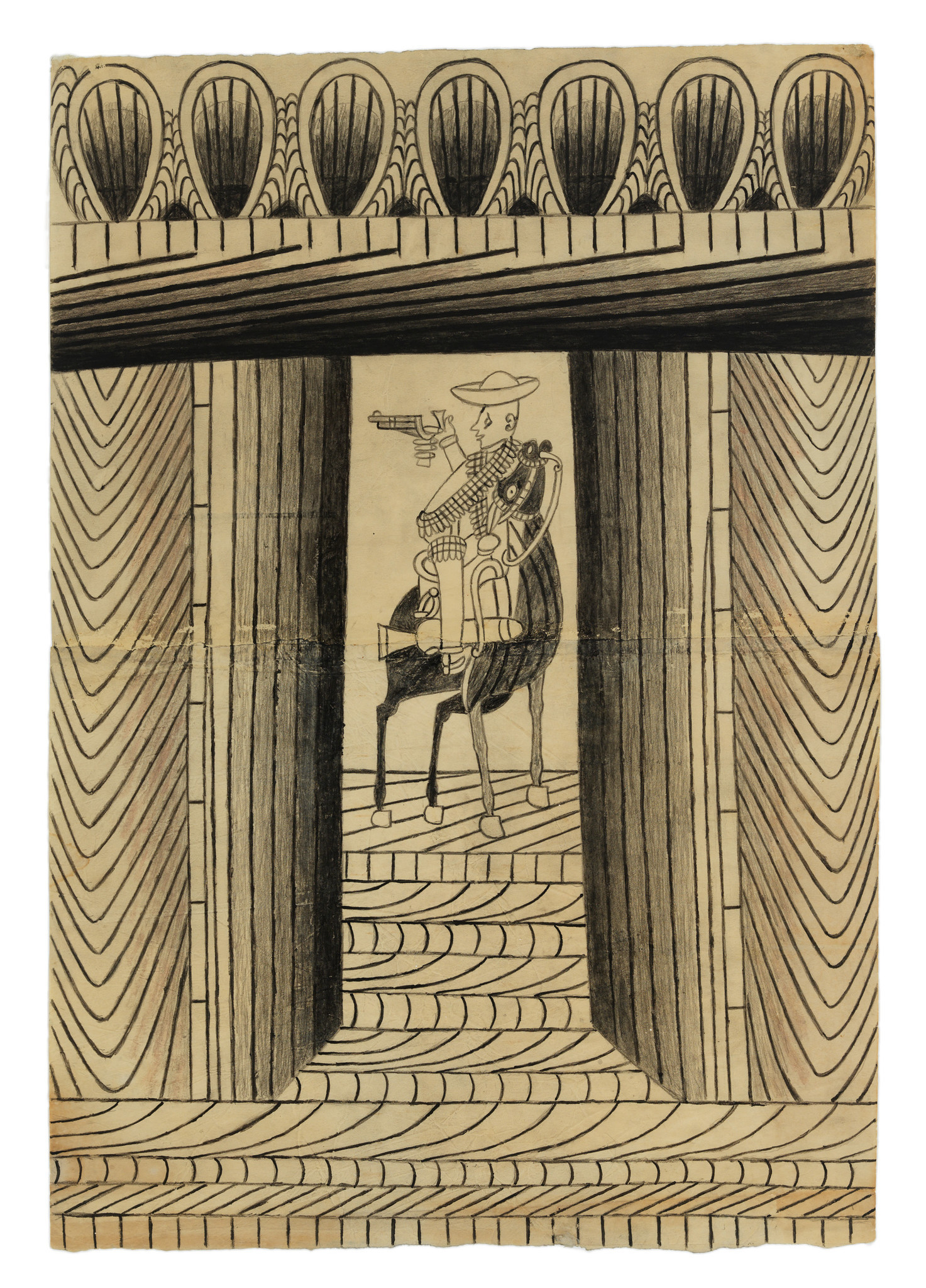

Martin Ramirez. Horse and Rider With Frieze. No date.

Gouache, colored pencil, graphite.

by Rafaël Newman

It’s the final day of February 2022, a month that began with the centenary of the publication, on February 2, 1922, of Ulysses, on what was also the 40th birthday of its author, James Joyce. Commemorations were held, among other places, in Dublin, where Joyce was born and which plays a central role in the novel, and in Zurich, where Joyce wrote parts of Ulysses, where he died, and where he is buried.

The commemoration in Zurich took the form of an all-day reading of sections of the novel at thematically appropriate locations throughout the city. The marathon was organized by friends of the James Joyce Foundation, a center for the study of the writer’s works under the direction of the eminent Swiss Joyce scholar Fritz Senn; and because I have myself been involved in other events organized by the Foundation, and count among my acquaintances people associated with it, I was asked to take part, on Saturday, February 5, as a reader.

By a happy chance, the section I was invited to read from, alongside Andreas Flückiger and William Brockman, two associates of the Foundation, at the James Joyce Pub in Pelikanstrasse in downtown Zurich, was the Cyclops episode, the 12th of the novel’s 18 chapters. This pleased me because I have cherished the episode for years, in part because my Greek teacher at high school had begun our reading of Homer’s Odyssey with the ninth book of that 24-book poem, in which the Greek hero cunningly escapes death at the hands of the one-eyed giant Polyphemus, and which serves as the template for Joyce’s episode; and in part because, when I first came to read Ulysses, at university in the 1980s, it was the Cyclops chapter that appealed to me most, as it contained what I found the most cogently political encounter in Joyce’s novel—and politics was what interested me most at the time. Read more »

By a happy chance, the section I was invited to read from, alongside Andreas Flückiger and William Brockman, two associates of the Foundation, at the James Joyce Pub in Pelikanstrasse in downtown Zurich, was the Cyclops episode, the 12th of the novel’s 18 chapters. This pleased me because I have cherished the episode for years, in part because my Greek teacher at high school had begun our reading of Homer’s Odyssey with the ninth book of that 24-book poem, in which the Greek hero cunningly escapes death at the hands of the one-eyed giant Polyphemus, and which serves as the template for Joyce’s episode; and in part because, when I first came to read Ulysses, at university in the 1980s, it was the Cyclops chapter that appealed to me most, as it contained what I found the most cogently political encounter in Joyce’s novel—and politics was what interested me most at the time. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Bill Murray

I

The boundaries between tectonic plates are where big things happen, lasting geologic things. They are among the most remarkable bits of land on earth. The mid-Atlantic ridge is one of those boundaries, the longest mountain range in the world, separating the diverging Eurasian and North American tectonic plates. Trouble is, it mostly lies undersea, so there aren’t many places you can inspect it.

In the Arctic there’s Jan Mayen Island. Farther south there’s the Azores, Ascension and St. Helena islands and the UK’s Tristan da Cunha way down in the middle of nowhere. And there’s Iceland.

As manifest in Iceland, to the east lies a raised lava ridge, the Eurasian plate, from which the North American plate, to the west, pulls up from the earth and apart.

The width of the point of contact varies. Just here it’s about a three foot deep grass covered crevasse. That’s a term mountain climbers use and it’s too dramatic for where I’m standing, really just in a ditch a little wider than your arms can reach. It’s pretty underwhelming, truth be told, bit it’s a historic ditch. A ditch full of history and portent. An auspicious ditch with worldwide ramifications.

Whatever you call it, it’s a singular place, a patch of grass you can jump down in and stand on a spot where the earth is coming apart. Elsewhere it’s twice the height of a man and filled with icy, transparent-as-the-ether water. Which is where we stop in a kind of Icelandic gulch.

“Now we are on the Eurasian plate,” our guide Sven says.

With a hop, “Now the North American.”

Hop. Europe. Hop. North America. You can change continents in Istanbul too but you have to drive across a bridge. Read more »

I forget just how I came to watch Steven Spielberg’s Jaws several years ago. Most likely I saw it on my Netflix homepage and, noting that I’d not seen it when it came out in 1975, I said to myself, “Why not?” I knew it had made Spielberg’s career and was generally regarded as the first summer blockbuster [1]. And John Williams’ two-note theme was by now as recognizable as the opening four notes of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.

I watched it, was shocked at the appropriate times – for example, when the shark first comes up behind the Orca, prompting Sheriff Brody to utter the best-known line in the movie, “You’re gonna’ need a bigger boat.”

And that was that.

Until a couple of months ago.

I decided to revisit Jaws. I watched the film several times, making notes. I watched Jaws 2 as well. It isn’t as good as the original.

“Why,” I asked myself, “is the original so much better than the sequels?” Two things struck me rather quickly: first, Jaws 2 was more diffuse than Jaws, and second, there’s no character in the Jaws 2 comparable to Quint, the Ahab-like shark hunter. On the first, consider the way the last two fifths of Jaws is devoted to the hunt while Jaws 2 wanders from plot strand to plot strand the entire film. As for Quint, I asked myself: “Why did he have to die?” Sure, he’s arrogant and abrasive, but that doesn’t warrant death. Something more is required.

That’s when the light went on: sacrifice. Quint, not the shark, but Quint, is being sacrificed for the good of the community. That in turn suggested the ideas of René Girard, the literary and cultural theorist who has come to see the myth-logic (my term) of sacrifice as being central to human community. I now had a way of thinking about Quint’s death.

Caveat: This runs a bit long. So pour some tea, a single-malt, whatever suits, and settle back. Read more »

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

After my several visits to Kerala, I wrote up an article, “On Life and Death Questions in India” for EPW, where I highlighted the welfare and demographic achievements of Kerala, the most advanced region in India in terms of many indicators of social democracy. Soon Raj and his colleagues (including my friend, T.N.Krishnan) produced a large, quantitative report for the United Nations Development Program, which brought to international attention the so-called Kerala model of development.

After my several visits to Kerala, I wrote up an article, “On Life and Death Questions in India” for EPW, where I highlighted the welfare and demographic achievements of Kerala, the most advanced region in India in terms of many indicators of social democracy. Soon Raj and his colleagues (including my friend, T.N.Krishnan) produced a large, quantitative report for the United Nations Development Program, which brought to international attention the so-called Kerala model of development.

Back to Delhi, I was soon after invited to two conferences which were somewhat different from the usual specialized technical conferences I was used to. One was a conference organized jointly by the World Bank and the Institute of Development Studies at Sussex on the general theme of how to achieve fair distribution and economic equality without sacrificing economic growth in developing countries. The emphasis was not so much on paper presentation with specialized research but more on thinking aloud on big issues. The conference was held in the grand surroundings of Villa Serbelloni, the conference center at Bellagio on a hill facing the beautiful blue Lake Como in Italy (the Villa’s history goes back a few centuries: it is claimed that Leonardo da Vinci was a guest there).

At this conference I met a number of important development economists, who became long-term friends; these included Albert Fishlow and Irma Adelman (both of whom were later my colleagues at Berkeley) and Lance Taylor (later at New School of Social Research), apart from Montek Ahluwalia (later a top economic-bureaucrat in Delhi) and Clive Bell (later a professor at Heidelberg), who were among the conference organizers and the editors of a subsequent volume titled Redistribution with Growth (for which they commissioned me to write a short section). Read more »

by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

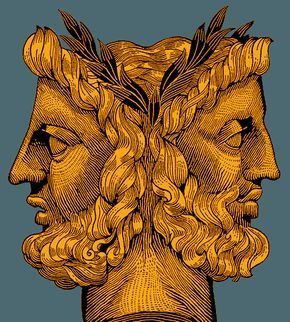

Carrying on an intellectual tradition is a Janus-faced enterprise. Like Janus, the Roman god of transitions, one must look both forward and backward. To start, a tradition must have a causal continuity with its past. The texts and debates from its crucial figures must be carefully preserved and interpreted; distinctive themes must be kept alive, insights appreciated, habits and approaches refined, and founding arguments clarified. Yet living intellectual traditions are not museum pieces. A viable tradition must be applicable to contemporary circumstances. Contemporary practitioners must demonstrate the relevance of their tradition by importing its characteristic principles, practices, and arguments into the fray of current debate. Naturally, this will occasion new challenges and problems for the tradition. Contemporary critics of the tradition will have innovative lines of objection, and material arrangements will change in ways that the founders did not anticipate.

Thus, a tradition’s distinctive insights will need updating and revision. Sometimes, more drastic measures are necessary. Given that any tradition will have internal debates at its founding or in its early development, those who seek to carry on that tradition must be open to the possibility that there are errors in the tradition’s inception – if the tradition’s founders disagreed, at least one was wrong; and maybe all were. The formative moments of a tradition are animated by debates over how the program’s most worthy insights can be developed and perfected. And what can be discarded. Accordingly, those who seek to keep a tradition alive must engage those debates anew, by answering challenges from external critics and by addressing internal disputes among fellow practitioners. Without this forward-looking face, one open to transitions and revisions, the tradition degrades into dead dogma. Read more »

by Paul Braterman

When those in authority withhold promised information, we must fear for the worst. That is now the situation at Imperial College. As I write, the President’s Board is considering erasing from public view the role of one of the College’s founders, TH Huxley, despite his distinguished contributions throughout his life to education, science, and the abolition of slavery and other forms of discrimination. It is also considering erasing JBS Haldane’s name because he once discussed eugenics, even though he strongly opposed to this movement in its heyday, on the grounds that it was scientifically unsound and merely a rationalisation for the dominance of the upper classes.

This perverse outcome is the result of a deeply flawed process, as I have discovered by examination of the public record, supplemented by information from within Imperial’s faculty. It may well be too late to change the Board’s decision, but it is never too late to learn from the events that have led to this debacle.

It is by now widely known by now that:

as part of the commendable activity of reviewing its past and encouraging diversity, Imperial College appointed a History Group to make recommendations,

that this recommendation has provoked widespread opposition among Imperial College academic staff and elsewhere,

that 40 distinguished academics have put their signatures to a letter of protest,

that these signatories include 17 members of Imperial’s own Faculty, Faculty at 11 other universities and research institutes, 19 Fellows of the Royal Society as well as several members of comparable overseas bodies, 4 Sirs, a Nobel Prize winner (Sir Paul Nurse), a Breakthrough Prize winner (John Hardy), a McArthur Fellow (Russell Lande), and many of our most distinguished science communicators, including, most relevant in the present context, Adam Rutherford, author of How to Argue with a Racist and Control; the Dark History and Troubling Present of Eugenics,

that these signatories include 17 members of Imperial’s own Faculty, Faculty at 11 other universities and research institutes, 19 Fellows of the Royal Society as well as several members of comparable overseas bodies, 4 Sirs, a Nobel Prize winner (Sir Paul Nurse), a Breakthrough Prize winner (John Hardy), a McArthur Fellow (Russell Lande), and many of our most distinguished science communicators, including, most relevant in the present context, Adam Rutherford, author of How to Argue with a Racist and Control; the Dark History and Troubling Present of Eugenics,

that the journal Nature refused to publish this letter, on the grounds that they regarded it as a petition, which they no longer carried (Huxley, of course, was among the founders of Nature),

and that, thanks to the initiative of an alert journalist, the letter eventually appeared, sandwiched between others, in the London Daily Telegraph, together with an article summarising its contents. Read more »

—of an interview with Jane Goodall

_____________________________________

life from dying comes

—life after life:

a ballet of treed chimps,

a great defining roar,

a thin thread lost

where are you, father?

(a name I never called you,

I called you, Dad)

yet there it is: father

half-ground of my issue,

half-ground of my being,

chimps throw rocks into a waterfall

to watch them drop, to hear them splash

they sit watching stones and water fall

what is this, this dead tree

with its skin of moss and mushrooms

pushing up and out, this light-giving

thing overhead in its brilliant cape of blue,

this light, splashing, falling down,

this hard and heavy thing

I heave into empty-what

to watch it fall and vanish

into a gleaming mirror-hole

in the ground?

life from death

where are you, father?

the forest makes no demands on me,

says Jane,

it doesn’t care that I’m here

what is this distance,

this insistent swath of lush

misunderstanding?

Jim Culleny, 12/30/20

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

Like other parents, we were delighted when our daughter started walking a few months ago. But just like other parents, it’s not possible to remember when she went from scooting to crawling to speed-walking for a few steps before becoming unsteady again to steady walking. It’s not possible because no such sudden moment exists in time. Like most other developmental milestones, walking lies on a continuum, and although the rate at which walking in a baby develops is uneven, it still happens along a continuous trajectory, going from being just one component of a locomotion toolkit to being the dominant one.

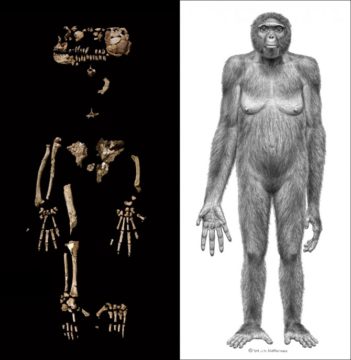

As paleoanthropologist and anatomist Jeremy DeSilva describes in his book “First Steps“, this gradual transition mirrors our species’s evolution toward becoming the upright ape. Just like most other human faculties, it was on a continuum. DeSilva’s book is a meditation on the how, the when and the why of that signature human quality of bipedalism, which along with cooking, big brains, hairlessness and language has to be considered one of the great evolutionary innovations in our long history. Describing the myriad ins and outs of various hominid fossils and their bony structures, DeSilva tells us how occasional walking in trees was an adaptation that developed as early as 15 million years ago, long before humans and chimps split off about 6 million years ago. In fact one striking theory that DeSilva describes blunts the familiar, popular picture of the transition from knuckle-walking ape to confident upright human (sometimes followed by hunched form over computer) that lines the walls of classrooms and museums; according to this theory, rather than knuckle-walking transitioning to bipedalism, knuckle-walking in fact came after a primitive form of bipedalism on trees developed millions of years earlier. Read more »

by Tim Sommers

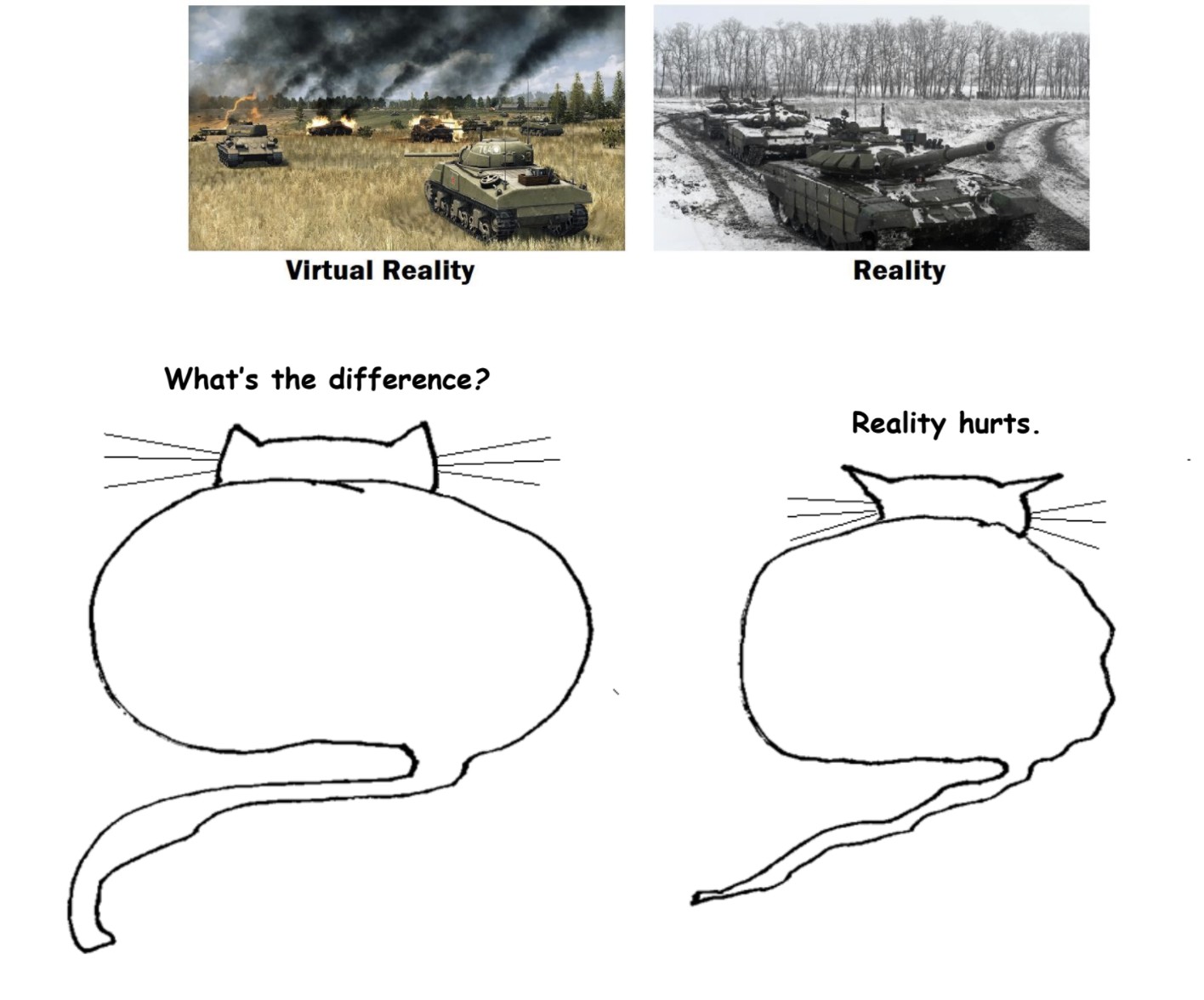

How do we know that the external world exists in anything like the form we think it has? Assuming that we think, therefore we are, and that it’s hard to doubt the existence of our own immediate sensations and sense perceptions, can we prove that our senses give us reasonably reliable access to what the world is really like?

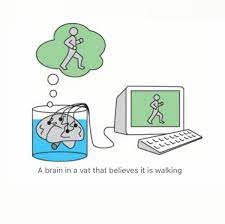

One thing that stands in our way is a variety of “skeptical scenarios” or “undefeated defeaters” (Knowledge is basically justified true belief without any undefeated defeaters.) Here are some well-known skeptical scenarios/defeaters: How do you know that you are not… (i) dreaming, (ii) being fooled by an evil demon; (iii) currently using a really good VR-rig; (iv) on a “holodeck” like the one in “Star Trek”, (v) currently in William Gibson’s immersive, plugged-in version of “cyberspace”, (vi) in “The Matrix” or, anyway, a matrix; (vii) in Nozick’s “experience machine”; (viii) a brain in a vat being electro-chemically stimulated to believe you are not just a brain and the world around you is going on as before; or (ix) part of a computer simulation? (You don’t need to recognize all of these to get the general idea, of course.)

David (“The Hard Problem (of Consciousness)”) Chalmers, in his new book “Reality+”, doesn’t want us to think of these as skeptical scenarios at all. Being a brain in a vat, he says, can be just as good as being a brain in a head. Most of what you believe that you know about, say, where you work, what time the bus comes, or how much is in your checking account is still true, relative to your envattedness, according to Chalmers.

It seems tenuous to me to claim that “most” of your beliefs could be true in such a scenario. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. February, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. February, 2022.

Digital photograph.

by Chris Horner

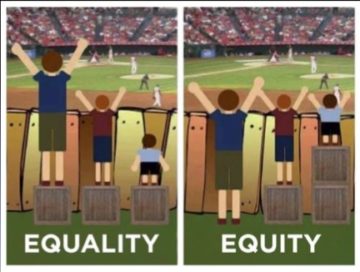

Equality v Equity

How should society go about the business of redistributing resources? Many people will be acquainted with the image featured at the top of this article. It is supposed to show the superiority of the notion of ‘equity’ – that is, giving people what they need to succeed, thus satisfying the demand for fairness that the equality approach is depicted as failing. Since people don’t start in the same place, due to gender, race, disability and so on, so the argument goes, an equal distribution is unfair: everyone goes up a bit, as in the image on the left, but since the differences haven’t been addressed, the result is unfair. So we need equity rather than equality. This is an example of an argument that looks persuasive at first glance, but which is deeply problematic when we consider it further. To see why, we need to go beyond the thought experiment approach to this issue, to see the social and political context in which it has become popular.

A first point to make is that no thoughtful advocate of greater equality has been blind to the importance of considering the needs of recipients. If equality is about justice, then it can’t just be mathematical equality. Giving the same amount of food to a malnourished person and a replete one would obviously be unfair. So if the current equity over equality argument is just saying this we could just see it just a difference in the terms one uses. But there is more going on with it than that. Read more »

by David Oates

Looking at this photo brings a rush of feeling – complicated, lovely, heartbreaking: a simple still life captured from the churning reality of the sea and the shore, which of course means also the weather, the wind, the atmospheric chemistries and grinding tectonics and magmatic uplifts and erosions and all high things toppling and washing down to the sea, all far things brought to shore, all shores grinded and washed away – all accumulating here, in this moment of randomness.

And . . . that this is beautiful.

Why is this beautiful? What excess of indifferent cosmic love has so arranged our universe, that dead randomness be beautiful?

Can you stand on the shore and not feel it? Or under the starry night?

Our hearts are broken by beauty. And mended by it. And we are undone, truly, in feelings and cycles beyond resolution. All we can do is go mute. Wipe the tear away. Turn our faces to a loved one, to see if these runes might be written there too.

Sometimes they are.

But now, in 2022, how are we to think of natural beauty and solace? When the seas are acidifying, rising, heating up. The whole planetary heat-budget going haywire. Species dying, ecosystems crashing. And worse to come.

This is an essay about lost refuges. Can I still stand on the shore and be restored, spiritually renewed? Yes. But, Reader, it is very hard work. Hard, heavy work. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Ethan Seavey

Why do I have to help?

Why do I have to help?Because I can’t just watch from inside the house any longer. Because the sun is setting behind grey clouds during a Chicago winter. Because you can’t recognize how dark it is getting until the streetlights switch on all at once. Because you don’t realize how cold your hands get while shoveling snow away from your tires until you try to fail to wrap them around the steering wheel. Because you’ve been working all day or because you’re late to work all night, and this snowstorm was the worst thing that could have happened.

Because it’s been fifteen, thirty minutes now and your terrifically impractical silver sedan hasn’t moved, and because I can see even through the window, even through the dim winterlight, that your tires needed to be changed years ago, because they are smooth as rubber bands and the two rear wheels spin wildly, freely, disobeying God or Newton or the settings of the universe.

Because two pedestrians, a greying white man and a woman out on a walk, they have already come to the rescue and because I am just sitting inside and watching. Because they shiver in the cold and I am warm. Because they have scavenged cardboard from the alley to put under the tires for traction and because this cardboard is already shredded and dampened and useless. Because I have dry cardboard and car mats stashed away. Read more »

by Dwight Furrow

Among the ideas in the history of philosophy most worthy of an eye-roll is Aristotle’s claim that the study of metaphysics is the highest form of eudaimonia (variously translated as “happiness” or “flourishing”) of which human beings are capable. The metaphysician is allegedly happier than even the philosopher who makes a well-lived life the sole focus of inquiry. “Arrogant,” self-serving,” and “implausible” come immediately to mind as a first response to the argument. It’s not at all obvious that philosophers, let alone metaphysicians, are happier than anyone else nor is it obvious why the investigation of metaphysical matters is more joyful or conducive to flourishing than the investigation of other subjects.

Among the ideas in the history of philosophy most worthy of an eye-roll is Aristotle’s claim that the study of metaphysics is the highest form of eudaimonia (variously translated as “happiness” or “flourishing”) of which human beings are capable. The metaphysician is allegedly happier than even the philosopher who makes a well-lived life the sole focus of inquiry. “Arrogant,” self-serving,” and “implausible” come immediately to mind as a first response to the argument. It’s not at all obvious that philosophers, let alone metaphysicians, are happier than anyone else nor is it obvious why the investigation of metaphysical matters is more joyful or conducive to flourishing than the investigation of other subjects.

Is there an insight here to be salvaged? Can this implausible argument about the glorious lives of metaphysicians be separated from the rest of Aristotle’s argument that philosophy is not only a way of life but the quintessentially superior way of life?

Aristotle argued that the activity of all beings is governed by their characteristic function which drives developmental processes. Reason is the characteristic function of human beings, and it’s the perfection of our capacity to reason so that we come to know the truth about a subject matter that constitutes flourishing. All human activity is directed toward this goal of flourishing although most human beings haven’t grasped its true nature or lack the necessary habits and self-control to achieve it. Thus, our pursuit of it is confused. Read more »

by David M. Introcaso

In late January the United States Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee released a draft discussion of its COVID-prompted public health bill titled, “Prepare for and Respond to Existing Viruses, Emerging New Threats, and Pandemics Act” (PREVENT Pandemics Act). Patty Murray, HELP Committee Chairwoman and Washington State senator, defined the bill as one that would “improve the nation’s preparedness for future public health emergencies.” We need to, Senator Murray stated further, “take every step we can to make sure we are never in this situation again.” The draft is fatally flawed because inexplicably the HELP Committee, the Senate “public health” committee, does not address much less recognize ever-increasing health harms caused by the climate crisis. As a result, the committee’s bill is what Orwell would term a “flagrant violation of reality.”

In late January the United States Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee released a draft discussion of its COVID-prompted public health bill titled, “Prepare for and Respond to Existing Viruses, Emerging New Threats, and Pandemics Act” (PREVENT Pandemics Act). Patty Murray, HELP Committee Chairwoman and Washington State senator, defined the bill as one that would “improve the nation’s preparedness for future public health emergencies.” We need to, Senator Murray stated further, “take every step we can to make sure we are never in this situation again.” The draft is fatally flawed because inexplicably the HELP Committee, the Senate “public health” committee, does not address much less recognize ever-increasing health harms caused by the climate crisis. As a result, the committee’s bill is what Orwell would term a “flagrant violation of reality.”

Preparing for “emerging new threats” appears unrelated to the Pacific Northwest’s recent 1,000-year heat wave, made 150 times more likely by Anthropocene warming, that killed 1,400 including Chairwoman Murray constituents, moreover seniors. In sum, last year produced 20, $1 billion climate-related disasters. Over the past five years these have cost Americans $750 billion. Last summer’s heat dome also killed Senate Finance Committee Chairman constituents. Unlike the HELP Committee, Senate Finance did hold, for the first time in nine years, a climate-crisis related hearing this session. However, Senator Wyden defined the climate crisis exclusively as a tax policy problem. In his opening statement, he argued, “Getting the policy right . . . is the whole ballgame.” If only. How does tax reform remedy the 58% of excess annual US deaths caused by fossil fuel emissions particularly when greenhouse gas emissions, moreover CO2, remain in the atmosphere for upwards of a thousand years. Read more »