by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

In both ISI and DSE there was one problem I faced in my research that was something I did not fully anticipate before. Some of the major international journals had a submission fee for research papers which was equivalent to something that would exhaust most of my Indian monthly salary. In the US authors mostly charged the fee to their research grants, which was not a way out for me. I once wrote about this to the Executive Committee of the American Economic Association (AEA), and suggested that for their journals they should have a lower rate for authors from low-income countries. I got a reply, saying that after careful consideration in their Committee meeting they had decided against my suggestion. Their rationale was a typical one for believers in perfect markets: since an article in an AEA journal was likely to raise significantly the expected lifetime earnings of an author, the latter should be able to finance it. (I visualized the dour face of an Indian public bank loan officer trying to comprehend this).

In both ISI and DSE there was one problem I faced in my research that was something I did not fully anticipate before. Some of the major international journals had a submission fee for research papers which was equivalent to something that would exhaust most of my Indian monthly salary. In the US authors mostly charged the fee to their research grants, which was not a way out for me. I once wrote about this to the Executive Committee of the American Economic Association (AEA), and suggested that for their journals they should have a lower rate for authors from low-income countries. I got a reply, saying that after careful consideration in their Committee meeting they had decided against my suggestion. Their rationale was a typical one for believers in perfect markets: since an article in an AEA journal was likely to raise significantly the expected lifetime earnings of an author, the latter should be able to finance it. (I visualized the dour face of an Indian public bank loan officer trying to comprehend this).

I also found out that using Indian micro-level data for a research paper in a mainstream American journal in those days was considered so exotic that more often than not the editors, even before reviewing the paper, would immediately suggest sending it instead to an Indian journal or at best a field journal. Read more »

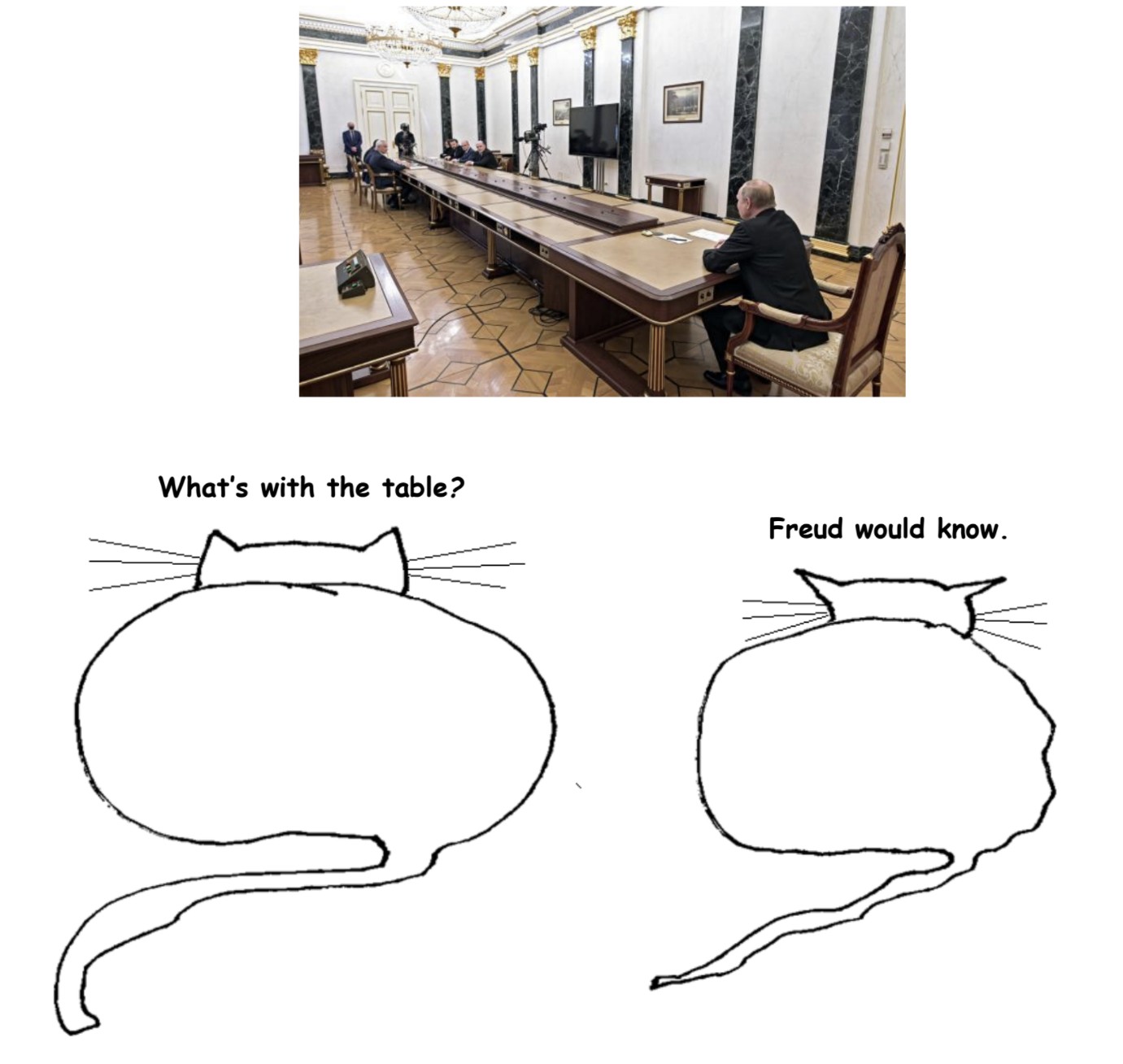

Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine is clearly a historically momentous event, already appearing to cause a seismic shift in the geopolitical landscape. What the long-term consequences will be are hard to say. The most obvious losers are the millions of Ukrainians–killed, injured, bereft, and displaced–who are the immediate victims of Putin’s onslaught. The most likely winner will probably be China, on whom Russia is suddenly much more economically dependent due to the sanctions imposed by the West, and who can therefore now expect Putin to dance to whatever tune it whistles.

Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine is clearly a historically momentous event, already appearing to cause a seismic shift in the geopolitical landscape. What the long-term consequences will be are hard to say. The most obvious losers are the millions of Ukrainians–killed, injured, bereft, and displaced–who are the immediate victims of Putin’s onslaught. The most likely winner will probably be China, on whom Russia is suddenly much more economically dependent due to the sanctions imposed by the West, and who can therefore now expect Putin to dance to whatever tune it whistles. The Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle (Workshop of Potential Literature), Oulipo for short, is the name of a group of primarily French writers, mathematicians, and academics that explores the use of mathematical and quasi-mathematical techniques in literature. Don’t let this description scare you. The results are often amusing, strange, and thought-provoking.

The Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle (Workshop of Potential Literature), Oulipo for short, is the name of a group of primarily French writers, mathematicians, and academics that explores the use of mathematical and quasi-mathematical techniques in literature. Don’t let this description scare you. The results are often amusing, strange, and thought-provoking. Despite living here for nearly three years now, I have no social life to speak of. At risk of sounding self-loathing, a not insignificant part of the problem is probably just me: I’m not the most social person in the world. Plus, there’s the pandemic, which hit six months after we moved here. But I don’t think it’s just me, or even just the pandemic. An awful lot of people who moved here as adults, decades ago, and are much nicer and more sociable than I am, have said the same thing: making friends in Toronto is hard.

Despite living here for nearly three years now, I have no social life to speak of. At risk of sounding self-loathing, a not insignificant part of the problem is probably just me: I’m not the most social person in the world. Plus, there’s the pandemic, which hit six months after we moved here. But I don’t think it’s just me, or even just the pandemic. An awful lot of people who moved here as adults, decades ago, and are much nicer and more sociable than I am, have said the same thing: making friends in Toronto is hard.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait With Trees. Seattle, February, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait With Trees. Seattle, February, 2022.

On 4 October 1957, in my mind’s eye, I was playing alone in the back yard when the radio in the breezeway broadcast a special news bulletin that changed my life. We had moved from Chicago to Minneapolis in 1951 and my parents had bought a recently built house on a dead-end street in a relatively cheap residential area out near the airport. The house was built in the modern suburban style that people called a ranch-style bungalow and its most interesting post-war feature was the breezeway, a screened-in patio attached to the house. The screens that kept flies and mosquitos at bay in warm weather were swapped for glass panels when the weather turned cold and we changed our window screens for storm widows.

On 4 October 1957, in my mind’s eye, I was playing alone in the back yard when the radio in the breezeway broadcast a special news bulletin that changed my life. We had moved from Chicago to Minneapolis in 1951 and my parents had bought a recently built house on a dead-end street in a relatively cheap residential area out near the airport. The house was built in the modern suburban style that people called a ranch-style bungalow and its most interesting post-war feature was the breezeway, a screened-in patio attached to the house. The screens that kept flies and mosquitos at bay in warm weather were swapped for glass panels when the weather turned cold and we changed our window screens for storm widows.

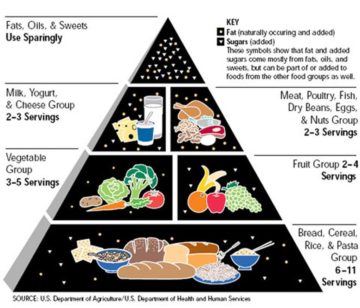

We have many choices when deciding what to eat. For most of human history, however, there has likely been little to no choice at all: people ate what was available to them or what their culture led them to eat. Now things are not so simple. As I mentioned in

We have many choices when deciding what to eat. For most of human history, however, there has likely been little to no choice at all: people ate what was available to them or what their culture led them to eat. Now things are not so simple. As I mentioned in

It’s my oldest memory. I am three, standing harnessed between my parents, in a brand-new two-seater 1959 Jaguar convertible roadster. We are on an empty gravel road someplace in Virginia and my Dad decides to let his new baby fly. I can see In front of me the windshield and, below, a gray leather dashboard that has two things of great interest…a speedometer and a tachometer. The motor hmmmmmms as he takes the car through the forward gears, the tachometer first rising and then falling, the speed increasing. The big whitewall tires are crunching the rough road; cinders are flying; we hit 60 MPH, then 70, then 80; and I’m clapping my hands and piping out “Faster, Daddy! Faster!” My mom goes from worried to furious “Slow down, Ernie, slow down!” As he passes 90, I look down for a moment and she’s slapping her yellow shorts. I peek at the rearview mirror and see a huge cloud of dust. 95, 100, and finally 105. Then without warning, and without using the brakes, he starts to slow, gradually downshifting; the speedometer and tachometer fall; and that’s where my memory ends.

It’s my oldest memory. I am three, standing harnessed between my parents, in a brand-new two-seater 1959 Jaguar convertible roadster. We are on an empty gravel road someplace in Virginia and my Dad decides to let his new baby fly. I can see In front of me the windshield and, below, a gray leather dashboard that has two things of great interest…a speedometer and a tachometer. The motor hmmmmmms as he takes the car through the forward gears, the tachometer first rising and then falling, the speed increasing. The big whitewall tires are crunching the rough road; cinders are flying; we hit 60 MPH, then 70, then 80; and I’m clapping my hands and piping out “Faster, Daddy! Faster!” My mom goes from worried to furious “Slow down, Ernie, slow down!” As he passes 90, I look down for a moment and she’s slapping her yellow shorts. I peek at the rearview mirror and see a huge cloud of dust. 95, 100, and finally 105. Then without warning, and without using the brakes, he starts to slow, gradually downshifting; the speedometer and tachometer fall; and that’s where my memory ends. The peopling of Polynesia was an epic chapter in world exploration. Stirred by adventure and hungry for land, intrepid pioneers sailed for days or weeks beyond their known horizons to discover landscapes and living things never before seen by human eyes. Survival was never easy or assured, yet they managed to find and colonize nearly every spot of land across the entire southern Pacific Ocean. On each island, they forged new societies based on familiar Polynesian models of ranked patrilineages, family bonds and obligations, social care and cohesion, cooperation and duty. Each culture that arose was unique and changeable, as islanders continually adjusted to altered conditions, new information, and shifting political tides. Through trial and hardship, most of these civilizations—even on some of the tiniest islands, like

The peopling of Polynesia was an epic chapter in world exploration. Stirred by adventure and hungry for land, intrepid pioneers sailed for days or weeks beyond their known horizons to discover landscapes and living things never before seen by human eyes. Survival was never easy or assured, yet they managed to find and colonize nearly every spot of land across the entire southern Pacific Ocean. On each island, they forged new societies based on familiar Polynesian models of ranked patrilineages, family bonds and obligations, social care and cohesion, cooperation and duty. Each culture that arose was unique and changeable, as islanders continually adjusted to altered conditions, new information, and shifting political tides. Through trial and hardship, most of these civilizations—even on some of the tiniest islands, like