by Mike O’Brien

This was supposed to be a fun and light-hearted post, filled with reflections on nature and shared spaces that had occurred to me while blissfully snowshoeing in an idyllic Canadian winter. Then a convoy of Brownshirts invaded my country’s capital and entrenched themselves in a lawless occupation, demanding the dissolution of our democratically elected government and the repeal of necessary public health measures. I tried to swear off writing about contemporary American politics last year, to safeguard my own happiness and mental health. But now that those American politics have, like the effluvia of an overfull septic tank, seeped and swelled up to my doorstep, I have to write about them again. I am not happy about this.

A primer for those who don’t follow Canadian politics (which is to say, almost everyone): a convoy of truckers and hangers-on (figuratively; hanging on to a truck crossing the Canadian prairies in January requires more commitment than any movement can muster) headed out from Alberta last week, aiming to install themselves in front of Parliament in Ottawa, in order to protest vaccination mandates for truckers entering Canada and the United States. 90% of Canadian truckers are already vaccinated, and most do not support this movement. Even if Canada lifted its vaccine mandate, unvaccinated truckers would still be barred from entering the US. It gets stupider. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. Anza-Borrego Desert Park, Calfornia, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. Anza-Borrego Desert Park, Calfornia, 2017.

“Sewer designs… For me, it took about a year to exhaust my fascination with the underground maze of waste. That’s when I realized the single most important point to grasp about designing sewer lines is that the shit must flow downhill. That’s all one needs to know. Nothing else matters.” So muses Emma, a smart young sewer engineer and the protagonist of Sara Goudarzi’s debut novel The Almond in the Apricot. The book takes us through the convoluted maze of Emma’s own inner turmoil that begins to blur the boundaries between her physical world and her dreams.

“Sewer designs… For me, it took about a year to exhaust my fascination with the underground maze of waste. That’s when I realized the single most important point to grasp about designing sewer lines is that the shit must flow downhill. That’s all one needs to know. Nothing else matters.” So muses Emma, a smart young sewer engineer and the protagonist of Sara Goudarzi’s debut novel The Almond in the Apricot. The book takes us through the convoluted maze of Emma’s own inner turmoil that begins to blur the boundaries between her physical world and her dreams. When I am not doing well in my own head, I turn to the tarot. While no substitute for therapy or psychiatry, the tarot has an ancient function that is symbiotic with these modern methods for coping with the wild unruliness of the mind. I know it sounds silly. But before there was psychology and medicine, there was magic, and that is not silly at all. People crave rituals and symbols; they crave narratives about themselves with which to play and to experiment. And the tarot is nothing if not an arcane form of play and experimentation with the idea of the self, packed with ritual and narrative and symbol. Magic, you see, is a very minor thing. It does not make great things happen, and, when it is practiced honestly and forthrightly, it does not claim to make great things happen. Instead, magic is meant to open up little moments, little apertures into self-understanding, that allow for the flourishing of subjects in an otherwise mean and obscure world. It is difficult to be a subject in the world; it is a task with no guidebook and with few obvious parameters. Little practices that seek after the integration of the self with the world, that seek to make distinct and clear not only who the self is but what the self means and is capable of accomplishing and being with the materials of the world at hand—these kinds of practices, which include both the tarot and psychotherapy (the latter being perhaps a practice of magic in our modern lives), make it

When I am not doing well in my own head, I turn to the tarot. While no substitute for therapy or psychiatry, the tarot has an ancient function that is symbiotic with these modern methods for coping with the wild unruliness of the mind. I know it sounds silly. But before there was psychology and medicine, there was magic, and that is not silly at all. People crave rituals and symbols; they crave narratives about themselves with which to play and to experiment. And the tarot is nothing if not an arcane form of play and experimentation with the idea of the self, packed with ritual and narrative and symbol. Magic, you see, is a very minor thing. It does not make great things happen, and, when it is practiced honestly and forthrightly, it does not claim to make great things happen. Instead, magic is meant to open up little moments, little apertures into self-understanding, that allow for the flourishing of subjects in an otherwise mean and obscure world. It is difficult to be a subject in the world; it is a task with no guidebook and with few obvious parameters. Little practices that seek after the integration of the self with the world, that seek to make distinct and clear not only who the self is but what the self means and is capable of accomplishing and being with the materials of the world at hand—these kinds of practices, which include both the tarot and psychotherapy (the latter being perhaps a practice of magic in our modern lives), make it

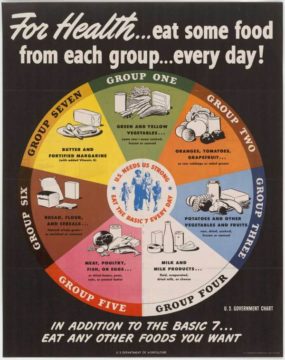

What to eat? A seemingly simple question, but one that has become increasingly difficult to answer. And why is that? My initial hypothesis is that as modern society becomes more and more distanced from traditional and local cuisines, people have less guidance as to what to eat; this puts increased pressure on individuals to make a conscious choice, but with unclear and often conflicting information about how to make this choice. In other words, people used to just eat whatever their grandparents had eaten, and this worked relatively well. Now, with an overabundance of choice and ignorance of one’s own past, we are lost, wandering through the supermarket aisles like a traveler lost in the woods. Thus, we see diets, meal plans, food delivery apps, and a myriad of other things jump in to fill the void that has been abdicated by family and community. But this story is perhaps so obvious that it does not need retelling. It is, after all, the story of the modern, global world. Nevertheless, it’s useful to pause, look around, and ask ourselves, “How did we get here? What is this place?” Let me sketch a few examples of people attempting to answer our initial question, “What to eat?” to help illustrate our general predicament.

What to eat? A seemingly simple question, but one that has become increasingly difficult to answer. And why is that? My initial hypothesis is that as modern society becomes more and more distanced from traditional and local cuisines, people have less guidance as to what to eat; this puts increased pressure on individuals to make a conscious choice, but with unclear and often conflicting information about how to make this choice. In other words, people used to just eat whatever their grandparents had eaten, and this worked relatively well. Now, with an overabundance of choice and ignorance of one’s own past, we are lost, wandering through the supermarket aisles like a traveler lost in the woods. Thus, we see diets, meal plans, food delivery apps, and a myriad of other things jump in to fill the void that has been abdicated by family and community. But this story is perhaps so obvious that it does not need retelling. It is, after all, the story of the modern, global world. Nevertheless, it’s useful to pause, look around, and ask ourselves, “How did we get here? What is this place?” Let me sketch a few examples of people attempting to answer our initial question, “What to eat?” to help illustrate our general predicament. Even though my ISI office was in the Planning Commission building in New Delhi I was living in an apartment complex far away in ‘Old’ Delhi, nearer Delhi University. The main attraction of staying there was the number of academic friends who lived in the same complex, apart from its being in a rather open, leafy, quieter part of the city (the hilly walkway at the back—called ‘the ridge’– was full of parrots and monkeys). My MIT friend, Mrinal, who stayed there arranged with the landlord for our accommodation.

Even though my ISI office was in the Planning Commission building in New Delhi I was living in an apartment complex far away in ‘Old’ Delhi, nearer Delhi University. The main attraction of staying there was the number of academic friends who lived in the same complex, apart from its being in a rather open, leafy, quieter part of the city (the hilly walkway at the back—called ‘the ridge’– was full of parrots and monkeys). My MIT friend, Mrinal, who stayed there arranged with the landlord for our accommodation. I come to praise bakeries past and present. And older men and women faithfully carrying out their duties to their grandchildren.

I come to praise bakeries past and present. And older men and women faithfully carrying out their duties to their grandchildren. Was it inevitable, this ongoing anthropogenic, global mass-extinction? Do mass destruction, carelessness, and hubris characterize the only way human societies know how to be in the world? It may seem true today but we know that it wasn’t always so. Early human societies in Africa—and many later ones around the world—lived without destroying their environments for long millennia. We tend to write off the vast period before modern humans left Africa as a time when “nothing much was happening” in the human story. But a great deal was actually happening: people explored, discovered, invented, and made decisions about how to live, what to eat, how to relate to each other; they observed and learned from the intricate and changing life around them. From this they fashioned sense and meaning, creative mythologies, art and humor, social institutions and traditions, tools and systems of knowledge. Yet it’s almost as though, if people aren’t busily depleting or destroying their local environments, we regard them as doing nothing.

Was it inevitable, this ongoing anthropogenic, global mass-extinction? Do mass destruction, carelessness, and hubris characterize the only way human societies know how to be in the world? It may seem true today but we know that it wasn’t always so. Early human societies in Africa—and many later ones around the world—lived without destroying their environments for long millennia. We tend to write off the vast period before modern humans left Africa as a time when “nothing much was happening” in the human story. But a great deal was actually happening: people explored, discovered, invented, and made decisions about how to live, what to eat, how to relate to each other; they observed and learned from the intricate and changing life around them. From this they fashioned sense and meaning, creative mythologies, art and humor, social institutions and traditions, tools and systems of knowledge. Yet it’s almost as though, if people aren’t busily depleting or destroying their local environments, we regard them as doing nothing. The theme of home—as a topic, question—is woven throughout Siri Hustvedt’s excellent new essay collection,

The theme of home—as a topic, question—is woven throughout Siri Hustvedt’s excellent new essay collection,  Sughra Raza. Inside Out, Boston, 2021.

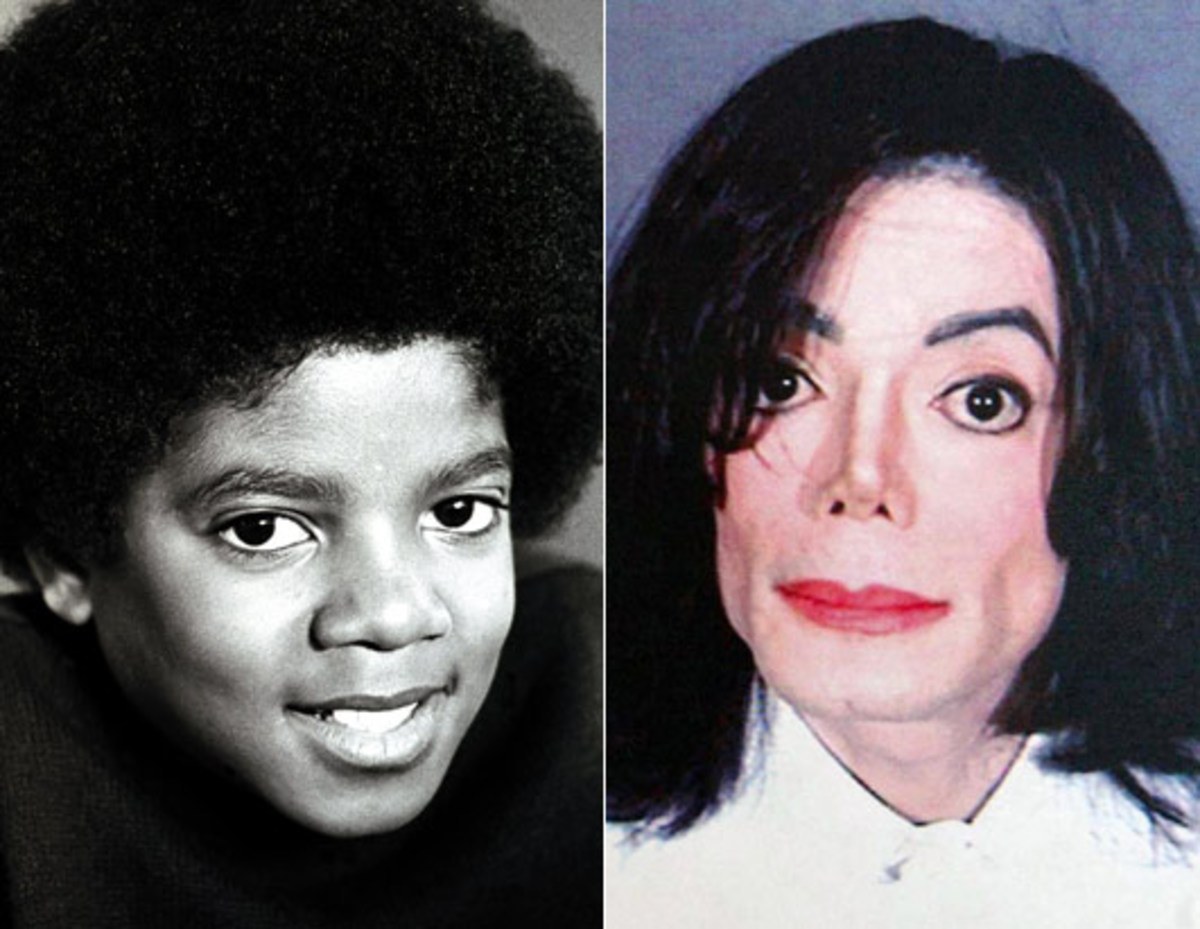

Sughra Raza. Inside Out, Boston, 2021. Over the course of more than a decade, Michael Jackson transformed from a handsome young man with typical African American features into a ghostly apparition of a human being. Some of the changes were casual and common, such as straightening his hair. Others were the product of sophisticated surgical and medical procedures; his skin became several shades paler, and his face underwent major reconstruction.

Over the course of more than a decade, Michael Jackson transformed from a handsome young man with typical African American features into a ghostly apparition of a human being. Some of the changes were casual and common, such as straightening his hair. Others were the product of sophisticated surgical and medical procedures; his skin became several shades paler, and his face underwent major reconstruction.

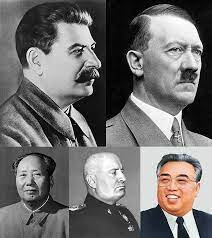

In this oft-reprinted quote from Hannah Arendt’s seminal work The Origins of Totalitarianism, many 21st century readers, particularly those engaged in pro-democracy movements in the United States and abroad, see Donald Trump and the emergent totalitarian formation of Trumpism sewn piecemeal onto the template that she constructed whole cloth from Hitler and Stalin’s political regimes. Although Trump hasn’t yet matched the political power, penchant for violence, or historical significance of Hitler or Stalin, he has made clear his disdain for democracy and exhibits a desire and willingness to use his power and violence to undo its institutional structures. For readers who are encouraged by the emergence of Trumpism and excited by its promise to make America great again, which includes inciting nationalistic pride, putting America’s interests first ahead of global concerns, policing public school curriculum for progressive ideological biases, packing the courts with sympathetic ideologues, and using banal procedural rules to derail the spirit of democratic negotiation and compromise then her work may provide you a cautionary tale regarding the potential implications of delivering on those promises.

In this oft-reprinted quote from Hannah Arendt’s seminal work The Origins of Totalitarianism, many 21st century readers, particularly those engaged in pro-democracy movements in the United States and abroad, see Donald Trump and the emergent totalitarian formation of Trumpism sewn piecemeal onto the template that she constructed whole cloth from Hitler and Stalin’s political regimes. Although Trump hasn’t yet matched the political power, penchant for violence, or historical significance of Hitler or Stalin, he has made clear his disdain for democracy and exhibits a desire and willingness to use his power and violence to undo its institutional structures. For readers who are encouraged by the emergence of Trumpism and excited by its promise to make America great again, which includes inciting nationalistic pride, putting America’s interests first ahead of global concerns, policing public school curriculum for progressive ideological biases, packing the courts with sympathetic ideologues, and using banal procedural rules to derail the spirit of democratic negotiation and compromise then her work may provide you a cautionary tale regarding the potential implications of delivering on those promises.