by Philip Graham

FRONT PORCH

FRONT PORCH

Tucked away in my mind is a secret neighborhood, with a winding street plan that arranges all the music that I have come to love. It’s a sprawling, noisy place, block after block of obscure or popular songs, odd genres or unusual instruments that I have listened to over a lifetime. Back in 1968, though, when I was beginning to develop my musical tastes, I spent most of my time in the House of Psychedelia, absorbing the trippy music that was so popular at the time, in a house that resembled a cross between a Buckminster Fuller dome and a Silly Putty dream of Frank Gehry.

My secret neighborhood also included the House of Pedal Steel Guitar—a ramshackle affair, its front porch empty except for a single rocking chair—which I walked past without regret. Why would I enter? Though the instrument’s sliding notes might soar as fluidly as a human voice, as far as I was concerned it was little better than the handmaiden of a musical genre beloved by love-it-or-leave-it racist conservatives.

But one day I took a few tentative steps from the sidewalk to the edge of the front porch.

Why?

Sweetheart of the Rodeo, by the Byrds.

I had faithfully followed the band’s invention of folk rock to their birthing of psychedelic rock, so when they decided to audaciously fuse rock and country, I was willing to follow, though not without some hemming and hawing.

The Byrds first announced this stylistic switch with one of Bob Dylan’s still-unreleased basement tape songs, “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere.” In the first few seconds of the song, the usual echoing overtones of Roger McGuinn’s twelve-string Rickenbacker had been replaced by the pedal steel of session musician Lloyd Green, who abandoned the instrument’s country-whiny cry and muscled the opening riff into burly rock and roll energy. No sobbing over a beer in a honkytonk here. Following the lead of new band member Gram Parsons, the Byrds were reclaiming an American music from its worst admirers.

I was too young at the time to know that Ray Charles had accomplished his own mission of revamping country music in 1962 with his Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music. He dressed up classic country songs in sleek soul and R&B big band arrangements, erasing any hint of pedal steel guitar. For their part, the Byrds had fueled their rock revolution with a deep dive into the music’s usual instrumentation. If my favorite band employed a pedal steel guitar in their continuing sonic explorations, how bad could the instrument be?

Yet country music in general and me? Outside of the Byrds’ music of that era, meh. In 1970, while hitchhiking across the country (the first of three not-entirely-insane journeys), I sat on the passenger seat of someone’s car driving through Kansas, or Nebraska, or who knows where, when a novelty song by Charlie Louvin rose up from the radio: “She’s a Come-and-Get-It Mama, and I’m a Never-Have-to-Call-Me-Twice Man.” I quietly hummed along so I would always be able to make fun of its catchy refrain.

It came down to a truce. Because of the Byrds, I might loiter now and then on the porch of the House of Pedal Steel guitar, but that was it. And this truce held for a decade. Until 1980, when I lived in the West African country of Ivory Coast, and a little rural music shop revealed a pedal steel guitar versatility I had never imagined.

FIRST FLOOR

The shop itself, parked across the street from the market of the small town of M’Bahiakro, looked as if it had been hammered together overnight. Yet inside, three sturdy walls of shelves displayed an array of record albums—only a single copy of each–whose covers faced out over a counter filled with the components of an advanced stereo system loud enough to broadcast the latest local popular songs to the farthest corners of the town.

Once a week my wife Alma and I traveled to M’Bahiakro to stock up on the offerings of its regional market. We lived in a tiny village 25 miles away, where Alma conducted her doctoral research in anthropology among the Beng people. And we never missed a chance to visit the record shop.

The LPs on the walls were the latest releases by musicians we’d never heard of and had no context for: Kiland & l’Orchestre Mabatalai, Fata Damba, Mory Kante et son Ensemble, Sir Shina Adewale, Sam Mangwana & the African All-Stars, Luango Franco, and King Sunny Adé. All we had to do was point to any album that looked interesting, and the shopkeeper happily spun it for a few minutes on the turntable. If we liked what we heard, money passed hands. Then we went about our business in the market, hunting down dried fish, onions, okra—whatever staples would help get us through to the next week.

When we returned an hour or so later, our bootleg tape was ready.

Back then, nearly every small town in West Africa boasted a small shop that sold bootleg music tapes. And for good reason: most people in small towns couldn’t afford a record player, and most music lovers who lived in the surrounding small villages had no access to electricity—we lived in such a village ourselves. But many people could afford a basic cassette player and the D batteries that powered them. All a music shop needed to succeed was a single LP of any hit record, which could then be copied onto Sony cassette after cassette after cassette.

One day I pointed at an album by someone called King Sunny Adé, and moments later it spun on the turntable. Talking drums bubbled out rhythms, and then something unexpected took over the groove. Damn if it wasn’t the unmistakable twang of a pedal steel guitar ringing out brisk melodic phrases.

One day I pointed at an album by someone called King Sunny Adé, and moments later it spun on the turntable. Talking drums bubbled out rhythms, and then something unexpected took over the groove. Damn if it wasn’t the unmistakable twang of a pedal steel guitar ringing out brisk melodic phrases.

I later learned that King Sunny Adé was a star of Nigerian Juju music and its competitive scene. Band leaders were always searching for some new innovative edge. When Adé wanted to add the sound of the goje—a single stringed African violin—for its gliding vocal sound, he discovered the acoustic instrument was too easily lost in the churning sound of his band’s 20 drummers and guitarists and singers.

Adé finally settled on an instrument that he thought came closest to the sound of a goje: a pedal steel guitar. Ademola Adepoju, a band member who knew a little something about the similar Hawai’ian slack key guitar, was quickly anointed as the band’s pedal steel player. Adepoju, however, had never heard American country music and so, untouched by the genre’s clichés, he adapted the instrument to his own ends, as can be heard on “Ma Jaiye Oni,” from Sunny Adé’s first international release, Juju Music.

That year in Ivory Coast, King Sunny Adé’s Juju music became a kind of comfort food for me, as it combined what I’d always considered a distinctively American sound with the talking drums so familiar in the village where we lived. Without realizing it, I had walked through the front door and into the first floor of the House of Pedal Steel Guitar.

SECOND FLOOR

Considering how King Sunny Adé had so triumphantly adapted pedal steel guitar to the traditions of Juju music, I shouldn’t have been surprised when, in 2001, I discovered Sacred Steel, a gospel music genre that has echoed throughout African-American Pentecostal churches since the 1930s. The best Sacred Steel players, pressing the wine from the whine of the instrument’s country music origins, are said to have the ability to coax out the presence of the Holy Ghost and draw it into the church. This is not a kneeling-in-the-pew-and-praying music, more often it’s a praise music, a shouting-out-your-faith music, because apparently the Holy Ghost appreciates some energetic encouragement before making an appearance.

I love Sacred Steel, but for me religious music has never been a call to root, root root for the home team. I guess you could say that I’m of the Many-Blind-Men-Pawing-an-Elephant persuasion. Who can possibly grasp an unknowable entity? I’m happy to embrace my all-too-human myopia, because a knowable God can diminish to the status of a superhero: resembling us, but with special powers like Spiderman or the Incredible Hulk.

What moves me most about devotional music is not its dogma but its passion. I can close my eyes, listen to Hildegard von Bingen’s floating choral prayers, or Alice Coltrane’s harp-drenched spiritual jazz, or Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s Qawwali ecstasies, and be transported over the specifics to the music’s unnameable spirit of yearning.

Sacred Steel is certainly no stranger to passion. Here, in “Train Don’t Leave Me,” two giants of the genre, Robert Randolph and Aubrey Ghent, engage in a joyous cutting session in a decidedly secular setting. But they might just as well be exhorting the faithful in a church. Though I’m not sure if Randolph and Ghent are coaxing out the Holy Ghost, or if instead that Holy Spirit is egging them on.

Sometimes the Holy Ghost prefers a gentler summons. Here, Dave Fonville plays the appropriately-titled song, “A Praise on the Inside.”

In exploring the various byways of Sacred Steel, I’d made it to the House of Pedal Steel Guitar’s second floor. Nearly twenty years passed before I discovered the third.

THIRD FLOOR

You could say that Saariselka, the duo of Chuck Johnson and Marielle Jakobsons, plays pantheistic music, or perhaps the benign devotions of a religion that hasn’t yet been invented. Regardless, the genre they embrace is known as Ambient Americana. Johnson was once a student of Pauline Oliveros, the legendary “deep listening” accordionist who, with Terry Riley and others, had a profound effect on the flowering of musical minimalism.

That’s the “ambient” part. Where “Americana” comes in is, of course, Johnson’s blending of the pedal steel guitar with Jakobsons’ sonic treatments, making it the perfect music–at least to me–to play while driving through the vast spaces of the American Southwest, past New Mexican mesas and mountain chains, past arroyos and long stands of cottonwood trees, past the kind of sun-drenched lonely landscapes that inspired an artist like Georgia O’Keefe.

Having made it to the third floor of the House of Pedal Steel Guitar, I took in the expansive views of the surrounding neighborhood, could hear the faint strains of distant music. And I began to wonder, How many other floors could there be?

That’s when I remembered the Mbari House of the Igbo people of Nigeria.

MY OWN HOUSE OF PEDAL STEEL GUITAR

In the spring of 1990, I was an invited American guest at Ivory Coast’s first literary conference, which ended up being held during a time of great turmoil in the country’s history. Long-time president Houphouët-Boigny had finally worn out his welcome, having built, beside his tiny natal upcountry village, a cathedral even larger than St. Peter’s in Rome. During the conference, protests erupted throughout the capital, Abidjan, and they mirrored demonstrations taking place in other autocratic African countries, inspired in part by the continuing news of Eastern Europe peeling itself away from the Soviet Union. One day, during a break between conference sessions, I read in a news magazine an essay by Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe, who compared these widespread calls for more political and artistic freedom with the story of the Mbari House of his own ethnic group, the Igbo.

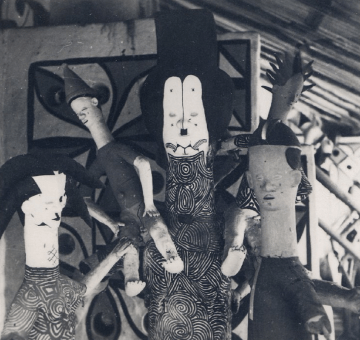

In Igboland, from time to time the earth goddess, Ala, would announce to diviners that a new Mbari House needed to be built. After the community completed the latest Mbari House, artisans then furnished it with sculptures, murals, and any other kind of art, even if strange or disturbing. The Mbari House’s only rule is that there is no rule—no subject matter is forbidden, and all aspects of the human condition and imagination are welcome. An Mbari House is considered an art form, and filling it up can take years to build because the whole endeavor is not about completion, it’s about the process of creation.

Now, after 52 years of exploring my own House of Pedal Steel Guitar, I think it’s a good idea to redesign. Why not remove the floors and walls that divvy up the house and leave one large echoing space for all the different musics that pedal steel can conjure? I can add Sneaky Pete Kleinow’s ferocious solos on The Flying Burrito Brothers’ “Devil in Disguise,” or jazz trumpeter Nils Pettar Molvaer jamming with pedal steel player Geir Sundsøl, or Daniel Lanois’ pedal steel gently bouncing along the lunar surface in “Weightless” (a song he co-wrote with Brian and Roger Eno that, now I come to think of it, is probably the ur-tune for the entire genre of Ambient Americana). I want a fluid place, a home that shifts shape as it calls up something holy, or a sunset lighting an arid valley, or an African village deep in the rainforest, or a crater on the moon.

My favorite pedal steel guitar music has always broken the dogma of what the instrument is capable of and how it should be played. In my own House of Pedal Steel Guitar, let it display, as Achebe wrote, “the full kingdom of human experience and imagination,” with a keening tone that uncannily resembles a human voice, one that’s able to speak many languages.