by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

Imagine finding out that intelligent life has been discovered on the far side of the galaxy. To learn that across the endless expanse of intergalactic space there exists a planet filled with new forms of life –and riches unimagined– if only we can find them. It won’t be as easy. Even in the 17th century people knew that flying to the moon in a chariot pulled by wild geese wouldn’t bring them face-to-face with aliens.

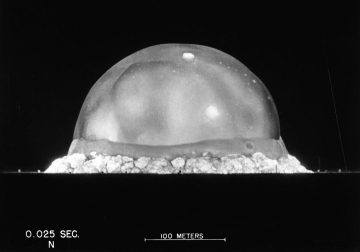

Maybe you’re thinking we could detonate all the nuclear bombs in the world on the dark side of the moon to get their attention? Well, that might work, but the aliens would have to be looking at just the right moment when the x-rays ripple past their telescopes. Astronomers have long been searching the radio waves of the universe for a message in a bottle. But so far, nothing has washed up.

Radio silence.

I became interested in Daniel Oberhaus’ book Extraterrestrial Languages after stumbling on a really exciting review in the London Review of Books. But it was not the history of SETI attempts to communicate with alien civilizations that excited me. What genuinely grabbed my attention was when the author made the obvious point that if we can’t even communicate with other species on our own planet, how are we supposed to communicate with aliens? Of course, we have been able to teach primates, Corvids, parrots and other birds, and certainly dolphins a lot of our human language — But how many words do we speak of Dolphinese or Chimpanzine? And what songs can we sing to in Whale-song? [Note 1]

2.

2.

Assignment: Write a four-to-five paragraph segment from the point of view (first or third, present or past tense) of a non-human character. Without saying explicitly who or what this character really is, ensure that the reader understands their nature.

Cosmographers report that in the distant past there were human nations that were ruled by dogs and great parliaments of birds which governed continents. Buddhist sutras were written by rhinoceroses. We were a multitude of kingdoms. Where salty marshes filled with fluttering flocks of finches flowed into rainforests dripping in moss and mushrooms. Through heavy mist, you could spy racing boars crashing into lumbering bears– and the bears would actually bow and apologize—even though they were not in the least at fault. It was a time when insects roared. Where bottlenose dolphins with human eyes swam up brackish canals tangled with waterlilies. A place of alligators piled up one on top of the other. And of deer with colorful flowers sprouting wildly from their antlers.

But all this changed when the insufferable philosopher Rene Descartes came on the scene. Descartes, who wrote that animals are without souls. Without minds and unable to feel pain, he said we were only capable of purely mechanical responses to impulses. Bête machine, he called us…Oh how I would have like to gore that French philistine right through the heart in late autumn when my antlers are sharp like daggers.

Despite my apprehensions about humans, I allowed the Spanish painter of the King to create my portrait because he alone among humans spoke my language. I don’t only refer to the way he uses a hallow pipe carved from cherry wood to do a passing impression of bellows, bleats, and grunts—but this strange and wondrous human communicates in perfume. Most humans practically knock us over with their scent. I am trying to be diplomatic here since you can smell them like garbage heaps from a mile away. And yet, this most peculiar painter approaches in sweetness, smelling faintly of musk. This is why I agreed to allow him to paint my portrait for the king. And this was how I began my mission to dismantle the imperialist humanist supremacist capitalist patriarchy.

You know, it’s harder than it looks at first glance to create a non-human POV that is not painfully anthropomorphizing the critter or creature. Novelist extraordinaire Jeff VanderMeer tweeted:

One way to convey the nonhuman, animal POV is to have a section where that POV is trying to act human to communicate with a human. This seems to reduce the possibilities for harmful anthropomorphism because the animal POV is itself admitting it is taking on a mask of the human. [Note 2]

Why is it, then, so hard for human beings to imagine the inner lives of animals and aliens? Why do we find it so difficult to move beyond Descartes and his notion of the Bête machine? Oberhaus, in his book on extraterrestrial languages, explains that scientists at SETI work under the assumption that intelligent life will have language. But what does that even mean? In the movies, whenever the aliens show up, we send in our linguists to crack their code. Since higher intelligence equals language. But in reality what would language look like in a creature that doesn’t have a mouth? Or a slug the size of the solar system that communicates by ESP? Or how about a sentient cloud of gas?

In the manifold possibilities for alien life, it is probable that we will share two things with them. One is that they will have developed under the same laws of evolution as the lifeforms on earth. And two is liquid water. Many at SETI also believe space aliens will speak in the language of mathematics. Not to say that math will be the same on earth as it is on alpha centari but it’s hard to imagine that creatures who build telescopes won’t understand us when we send our signals, broadcasting in the lyman alpha—or counting to ten in UV bursts, pausing for five, then counting to ten—over and over again…

3.

Honestly though, instead of space aliens wouldn’t you prefer to start your own interspecies crowd with your local dog or cat?

I, for one, agree with Stephen Hawking that in addition to the laws of evolution and liquid water, the other thing we are likely to share with aliens is resource scarcity. So, do we really want to be broadcasting our position in space?

(No~~~!)

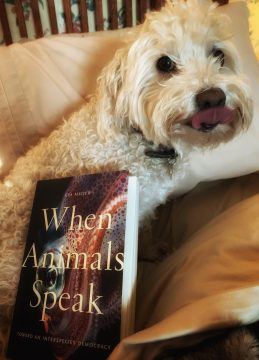

Just think about the fellow non-human animal friends in your life. Like my wise and brilliant pup, who does an excellent impression of a Zen monk. Or how about our blog cats here on 3 Quarks Daily, the incomparably wise cats of Catspeak?

And what of Pence’s pet fly? And Bernie’s bird? My Octopus Teacher…. Animals know a lot, and we need to listen to them, right?

“Of course animals speak!” says Eva Meijir, in her thrilling new book When Animals Speak: Toward an Interspecies Democracy.

According to the philosophical tradition since the time of Descartes, however, animals were not granted with language, which also meant they did not have minds or souls. Modern philosophy posited two distinct substances in the world: bodies, which obey the laws of physics and are mechanistic; and minds, which are non-physical and eternal. The soul-less bodies of animals were viewed as being only capable of mechanical responses to impulses. Incapable of feeling pain, unable to communicate in language or granted with reason, they have been viewed as object resources. Hence the term Bête machine.

It is important to note that in this traditional understanding, it is only human beings which are granted consciousness. Leading neuroscientist Christof Koch, in his book Consciousness: Confessions of a Romantic Reductionist, describes being raised in the Roman Catholic faith, and he movingly describes how his own scientific journey in the field of consciousness studies began with his vehement rejection of the church’s insistence that dogs don’t go to heaven. And this religious notion was carried into science and informs much of our industrial animal and agricultural practices. Indeed, you will cringe to learn that until quite recently, scientists were performing amputations on octopus limbs without any pain relief, because they did not recognize that animals feel pain as we do. [Note 3]

Rejecting this kind of Western dualism, Eva Meijir suggests we look at language not in terms of representational, Kantian correlationism, but rather in the way Wittgenstein saw it. Wittgenstein’s language games, she reminds us, posits language not in terms of words alone, but rather as being embedded within the social context. Language is an attunement to mood and shared practices in our own species, and this is surely something that other animals share with us. We humans have body language and gestures, eye contact and endlessly varied nonverbal forms of communication, including music and signs. Humans utilize the shared social context to communicate in ways that are fundamentally dependent on our physiology. And Meijer is telling is in the same way, so too do bats employ ultrasound, whales sing songs, and what of my dog’s uncanny use of ESP to communicate? [Note 4]

In much the way we have to approach SETI communication in terms with communicating with creatures who might not have eyes, ears and a mouth or who think in math, so too must we approach animal communication in terms of their bodies. To speak in the music of whales and the roar of insects? Or the fragrant language of deer?

4.

I dreamt I was in Alaska walking on soft, spongy tundra. Colorful wildflowers were sprouting up here and there. Suddenly, I wanted to take off my shoes and walk barefoot so I could feel the earth between my toes. I can’t even remember the last time I did that. Maybe when I was a kid? Slipping out of my sneakers, blue butterflies flew out of my shoes.

5.

I believe we are on the precipice of a new paradigm. More and more intellectuals—from Timothy Morton, Eva Meijir, and Paul Kingnorth’s Dark Mountain Movement to Bay Area Greats: Donna Haraway, Anna Tsing, Michael Pollan and Jenny Odell, we are hearing about a new way of being in the world. Starting with the Great Donna Haraway, these thinkers are not only telling us we need to stay with the trouble, but they are heralding a new age of interspecies democracy and solidarity with non-human people.

So, how do we talk to animals? Well we start by engaging in deep listening, says Meijir, Odell, Tsing and Haraway. All phenomenal female thinkers! [Note 5]

Anthropologist Anna Tsing begins her long meditation on late-capitalist commodity chains and devastated landscapes by considering the way Enlightenment philosophy was built on the concept of mind-body duality to view nature as set apart from human beings. While it may be grand and universal, “Nature” is also passive and mechanical, she says. Nature is seen as a backdrop. An endless resource. Something to be efficiently utilized.

This is why Timothy Morton resists the term Nature—positing an abyss between humans and the rest of the natural world.

For this same reason, Tsing avoids the use of the word “anthropocene,” instead describing our current state of being as one of “post-capitalist ruin.” This is crucial, for according to Tsing, the history of the human accumulation of wealth has not only trashed the environment but has also rendered our human selves into resources. This has led to the state of deep alienation in which we find ourselves. From economic theories of self-interest to scientific theories of the “selfish gene,” we have come to view ourselves as being isolated: encapsulated in bodies and alienated from the rest of nature and our fellow critters.

And it is in this lack of understanding of interconnectedness that is leading to our ruin.

Haraway is wonderful in bringing in Hannah Arendt to this conversation in her call for us to wake up, to not ignore and never turn away from the trouble. The sky is falling and we cannot look away (either in denials or worse in smug blame gaming just before we head out and load up at Costco). But what can we do? Well, we can start by showing up and listening. Haraway is one who believes the planet itself will survive and so will some critters—maybe not us— but some will survive the great extinction taking place and we can be present to the trouble by looking at connections. For me, her book was one of great hope. In bringing together like-minded scientists, artists, ecologists and traditional peoples who saw the world in terms of the relationships rather than individual subjects and objects. This is embodied in the idea of “kin.”

6.

Is this the end of the world as we know it? Or is this literally the end of the world?

Although the stakes are dire, the message remains optimistic: these thinkers are heralding in a new age. They ask how we can move beyond 24/7 patterns of endless production and consumption and transcend the technological understanding of being that views everything as resource at hand. How can we be grounded locally and see ourselves as part of an inter-dependent community of family businesses and family farms– an inter-species crowd even? And most importantly, how can we raise our kids not to become producers and consumers in the great war between the haves and have nots but as part of an interconnected world where time is no longer money. And to me, this has always been the saddest thing of all: that we force our kids to jump through these hoops that we know in our hearts only further add to the alienation that they will feel with nature and each other.

We all know that our model of endless growth, personal optimization and “consumerism as citizenship” is simply not sustainable. Not for the planet and not even for those winning the race to the top.

We are optimizing ourselves into oblivion.

Seriously, not only are we clueless in talking with space aliens, but we are deaf and blind to our fellow critters and to the earth—our beautiful blue green planet—itself.

My friend Erica, who is a historian of China says, “it’s as if all these American social scientists have suddenly discovered the porous and interconnected self of Buddhism, Confucian and Daoism. Well great. It was about time!

++

Books That Changed the Way I look at the World

Notes

1) I had never seen the image of the first moments of Trinity before. Timothy Morton mentioned in his book Hyperobjects that this photograph was banned at first because it was considered provocative. I have to say I think it is terrifying. My friend Derek, an astronomer, says: I think much of the weirdness of these photos may come from the extremely short exposures, as brief as 10^-6 of a second (the camera was capable of 10^-9 second exposures) which freeze the action of these incredibly violent events and make them palpable, almost solid. Video about rapatronic camera here.

Also, here is an interesting article about the Order of the Dolphin, early SETI attempts to communicate with dolphins.

2) Head of a Stag, by Velázquez. Sadly, that portrait was of an already killed animal. Perhaps killed by the king, the portrait is supposed to have been created to adorn the royal hunting lodge. My writing exercise is for a class I am taking at UCLA Extension, called: writing the fantastic. And was based on the philosophies of Timothy Morton and Eva Meijir.

I found a cherry wood trumpet for calling deer like the one in the story—but was sad to find out that they are used to stalk and kill deer, not talk to them. It never ceases to get my pup’s attention, he immediately runs over wagging his tail and sniffing wildly… endlessly curious and intelligently trying to figure out why mom is sounding like a stag. I want to get this next.

3) This post is part three in a three-part series on animal consciousness and Descartes. Please see Translating Descartes and Do Octopuses Have Souls

4) Like Timothy Morton, in his book Humankind: Solidarity with Non-Human People, Meijir takes on Heidegger, and I would say that–along with Donna Haraway–these thinkers not only mitigate some of the problems in Heidegger’s work but they make radical improvements to it. For years, I corresponded with Hubert Dreyfus about Heidegger’s concept of World and how that is different from culture? Culture, including language, is like the water that fish swim in. It informs and enables everything… so how is culture different from Heidegger’s idea of Worlding? And of course, Heidegger didn’t just mean culture in general, he took his terrible wrong term here, since culture to him meant German culture. This is to say that Heidegger was not just a lousy human being, like many artists or physicists or philosophers but rather his philosophy had an inherent suicide bomb hidden within it. Morton and Meijir say no to this idea of world as culture based in language. Heidegger claimed to be dismantling Descartes but on this he remains Cartesian in seeing human beings as beholders of language and therefore as beings who know the world. Heidegger saw animals as being “poor” in world… that is, like Descartes, human beings were separated by an ontological abyss from other animals ==we had minds that think thoughts in language. That is why he said language is the abode of being.

Morton takes this to the genius realm by bringing in Marx. And this is how he begins his own mission to dismantle the imperialist humanist supremacist capitalist patriarchy. Morton is exciting.

5) In 2017, I wrote a long essay on the concept of deep listening. Please see the Sound of Lotus Blossoming. … being embedded in a “soundscape” demands a certain two-way, give-and-take hearing –or to use the philosophical word– it demands an attunement of oneself to the local environment/community and to place (terroir). That is because when you stop and listen, you thereby come to belong to the land as much as the land belongs to you–even if just in that moment. The world is no longer a resource to be efficiently consumed but instead becomes lit up and embodied with voice and with sentiment. Reading: Manifesto for Living in the Anthropocene by Katherine Gibson and KQED: How ‘Slow Looking’ Can Help Students Develop Skills Across Disciplines