by Rafaël Newman

A system update recently downloaded to my cellphone included artificial intelligence capable of facial recognition. I know this because, when I subsequently opened the “Gallery” function to send a photograph, I discovered that the refurbished app had taken it upon itself to create a new “album” (alongside “Camera”, “Downloads” and “Screenshots”) called “Stories”, within which I found assemblages of my own pictures, culled from all of those other albums and assorted thematically, evidently because they depicted identical, or similar, figures.

A system update recently downloaded to my cellphone included artificial intelligence capable of facial recognition. I know this because, when I subsequently opened the “Gallery” function to send a photograph, I discovered that the refurbished app had taken it upon itself to create a new “album” (alongside “Camera”, “Downloads” and “Screenshots”) called “Stories”, within which I found assemblages of my own pictures, culled from all of those other albums and assorted thematically, evidently because they depicted identical, or similar, figures.

These AI-authored visual narratives had been given names, for the most part simply the date on which the visual elements had been created or sourced. In one case, where that date was associated on the template calendar with a particular observance, the “story” had been given that name: “Father’s Day,” for instance, had more or less accurately assembled photographs of me and my brother at an eponymous event; in another, a collection of snaps of my kids at various ages, the algorithm had wanly suggested “Memories” as an appropriate title, while, perplexingly, pictures taken during a family holiday in Riga had been collected under the inscription “The Royal St. John’s Regatta”, presumably because an event by that name had also taken place somewhere on the day date-stamped on my rainy Baltic souvenirs.

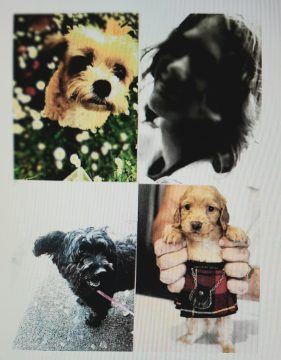

The “story” that bemused me most, however, had been given the title “Dog Days” (or “Hundetage”, since I have yet to change the operating-system language on the apparatus I purchased here in Zurich). “Dog Days” contained a collection of all of the pictures of dogs to be found on my phone: of which there is a surprisingly large number, given my own deficient ability to form an affective connection to animals, house pets included.

I had apparently taken and stored photographs of my mother-in-law’s dogs, past and present, as well as of a friend’s tiny Bolonka, which had pantingly accompanied us on a recent hike in the Emmental hills, although she was for the most part transported up to alpine meadows in a brocade bag. There was also an assortment of humorous dog “memes” for the robot to select from, which I had screenshotted for the ephemeral amusement of various correspondents.

Now, among the items from which this canine fumetto had been composed, one stood out: in part because it was in black and white, a rare effect these days; and in part because its subject was manifestly human. In fact it was a close-up of me, age 14, which I had re-photographed from an analogue snapshot in my father’s collection for a purpose now forgotten.

My initial response was indignation: a machine had classed me as a beast! And not just any beast, either, but one whose name commonly serves as an opprobrious epithet; whose proverbial loyalty is outweighed by its notorious obsequiousness, by its low habits and unpredictable reversions to dangerous savagery; whose famously deficient industry (“lazy as a dog”) is invidiously tempered by a craven zeal for transporting carrion to its killer master. Had mine thus been adjudged a dog’s life? Had my youthful physiognomy portended cringing obeisance, the flatterer’s lack of principle, indifference to cutlery, and a taste for perverse, onanistic hygiene? From the paragon of animals, had I now been demoted to the rank and file–by a computer program?

That the machine had simply made a category error was quickly explained, my daughter assured me when I showed her the collage. At age 14, my olfactory organ had already begun to outgrow my adolescent face, giving me a decidedly nose-forward, dog-like aspect, while the shaggy locks I had sported in the late 1970s could easily be mistaken for the floppy ears of an Afghan. And my fawning gaze–had my father taken the photograph?–could easily be read as expressing that unconditional love for which dogs are prized by their proprietors, but which has always caused me to shiver: because, like the uncannily treed wolves in Freud’s account of the Wolfman, whose immobility was said to represent the frenzied activity of the primal scene, the unwavering gaze of the domestic animal seems to comprise its own undoing, a serenity that threatens to cede to renatured bestiality as the stillness of the adoring companion gives way to springing attack, fangs ripping at the throat.

None of these reflections was particularly reassuring. What ultimately reconciled me to the inclusion of my likeness in a gallery of dogs was the memory of my own life during the period when the photograph was taken, and my reflections on a certain religious practice in ancient Athens: a rite of passage involving the assembling of a group of young people under the aspect of animals.

In the mid-20th century, excavations near the Greek capital uncovered the site of an archaic cult of Artemis, the goddess of hunting and wild animals notorious for her role in the sacrifice of Iphigeneia at Aulis, and the start of the Trojan War. At Brauron, some 30 miles from Athens, the archaeological evidence suggests, young, unmarried Athenian women would engage in a ritual that involved “playing the bear,” an animal sacred to the goddess, thus expiating the crime of its death at the hands of hunters while also preparing themselves for the symbolic “sacrifice” of marriage, in a chilling but ultimately propitious re-enactment of mythological deception and death. The sister of Apollo and a child of Zeus, Artemis is at once the patron of hunters and the protector of their prey, and thus inhabits a liminal space: “[Artemis] is the deity who mediates between the savage world of wild animals and the tool-using (and just as savage) world of humans,” writes Stephanie Budin in a study of the deity. “As goddess of the wilds, her cult marks transitions between the wild and the civilized, and between political domains. She helps girls become women, and more importantly, mothers… In most of her functions, to one extent or another, Artemis is the goddess who presides over changes of states of being.” In Chœurs de jeunes filles en Grèce archaïque, his germinal study of the function of the chorus in archaic Greek culture, Claude Calame notes that “the cult of Artemis serves to resolve the contradictions arising from the crisis of feminine puberty”. Artemis thus helped the young Athenians move from one status to another, both socially and physiologically: from daughter to wife, from immature to mature–and from wild to civilized. By “playing the bear”, like the Cub Scouts of a much later age, the girls of ancient Athens donned one last time the vestiges of their infantile, pre-sexual, pre-civilized state, as symbolized by their animal disguise, before putting off that aspect and consecrating themselves to their new, societally ordained gender role: as adults.

But what had any of this to do with me? In 1978, when the photograph was taken that would eventually lead to my being assigned canine status by a robot, I was in the midst of my own transition: from a rural (or at least suburban) environment in British Columbia to the centre of Toronto, Canada’s largest city; from a childhood spent with a single mother and in proximity to my father to membership in a new, “blended” family, with stepfather and step-siblings; and from pubescent androgyny to an initial submission to societally ordained gender, undergone shortly after the photograph was taken during an extended visit to the hairdresser, under pressure from an influential schoolfriend, an aficionado of punk and New Wave music and a dedicated enemy of anything that signalled outdated and uncool hippie, disco, glam, or heavy metal affiliation.

Most crucially, however, and with the longest-lasting results in my life, I was on the threshold of an induction into the pleasures of poetry. Now, my father is a poet, and in 1978 he was still teaching workshops in poetry in the Creative Writing department of the University of British Columbia, so poetry was not new to me at that age; indeed, I had earlier that year already tried my hand at parody and genre verse, inspired notably by the ongoing and pleasantly medieval-sounding “Year of the Three Popes”. But what truly gave me the confidence to write poetry, and to begin to think of myself as a poet, was my friendship with Eric Miller, a fellow student at Jarvis Collegiate Institute, where we shared a Grade 12 history class, among other instruction, and who was himself immersed in poetic production, and consumption: in particular, of the work of Dylan Thomas.

Eric taught me to revere Dylan Thomas, but in truth, it wasn’t hard: not for a 14-year-old would-be man, enthralled by the Welsh poet’s incantatory, druidic language, always just on the verge of portentous, magical incomprehensibility, as in the vatic call and response of “Do not go gentle into that good night”, his celebrated villanelle about Oedipal triumph couched as filial piety; by the cultured masculinity of his performance on recordings; and by his elevation to august symbolist heights of the most sordid rites of passage (such as, notoriously, masturbation, in “My hero bares his nerves”, written while Thomas was still a teenager). Finally, there was his beautiful, terrible, tragic death by alcoholism, not yet 40, having pursued his ruin in the very same district of Manhattan still infamous in that very turn of our current year, 1978/1979, for the dreadful demise of Sid Vicious, our generation’s own poète maudit. As one of his biographers has written, Thomas “exhibited the excesses and experienced the adulation which would later be associated with rock stars.”

Dylan Thomas had had youthful adulations of his own, of course, chief among them James Joyce, whose influence on his writing was sufficiently palpable that Thomas was obliged on occasion to deny it. This was a tall order, given that the title of his 1940 collection of short stories, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog, is an explicit play on Joyce’s semi-autobiographical bildungsroman, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, published in 1916. (In fact, while claiming that the title had been tactically chosen to increase book sales, Thomas did allow that he had been importantly affected by Joyce’s Dubliners: an anxiety of influence surely confined to his prose, for Thomas’s lyrics stand, by any measure, head and shoulders above the doggerel in Joyce’s Pomes Penyeach.)

How uncannily correct the robot algorithm had been, then, to induct that likeness of the ephebic me into a canine fraternity, and thus to commemorate my own moment “between the savage world of wild animals and the tool-using (and just as savage) world of humans”. Like those girls at Brauron, I had been called upon (by artifice, in my case, rather than by Artemis) to join the savage ranks to which I was on the verge of bidding farewell. The tools that I was to adopt upon entry into that human world were not the warrior’s sword, the hunter’s spear, or the priest’s sacrificial knife, but the poet’s pen, the writing pad, the word processor, and all the standard verse forms, especially the sonnet, even on occasion the sing-song villanelle. And if I was indeed to find the world of humans, now and then, to be just as savage as that of wild animals (at least as I imagined that world to be), then poetry would serve me both as a guarantee or promise of a coming civilization, and as a souvenir of my own successful emergence from a chorus of beasts, to solo performance as an adult human.