by Bill Murray

I

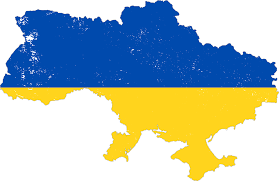

Russia’s war on Ukraine is realigning geopolitics everywhere you look. The Germans and French want the conflict to end immediately. Others won’t be heartbroken to see fighting continue to degrade Russian capabilities. The UK, Poles and Balts come to mind here. An idea is settling in that the US, too, doesn’t entirely mind fighting Russia to the last Ukrainian. There’s no denying the war is less painful from forty five hundred miles away.

Look north and if Finland and Sweden join NATO, overnight the Baltic Sea becomes the beating heart of European security. The shallow, enclosed Baltic hasn’t played such a heady role since the days of Napoleon. Vilnius and Riga never dreamed of such proximity to power.

In 2019 Mikhail Saakashvili, a previous victim of Russian aggression, predicted Russia’s next attack would come against Finland or Sweden. He was wrong, but he might not be wrong forever. That’s the fear that fuels an astonishing rush toward strategic realignment around the Baltic Sea.

Finnish President Sauli Niinistö is two years shy of wrapping up his second six year term. The 73 year old son of a newspaperman and a nurse from Finland’s southwest coast, Niinistö consistently polls as the country’s most revered figure.

He was in Washington a week and a day after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, already working to insure the American administration’s blessing for Finland’s accession to NATO. The Finns hold their president in such regard that his backing of Finland’s coming NATO application should insure the peoples’ approval.

Niinistö put it this way: “Sufficient security is where Finns can feel that there is no emergency and there won’t be one.” Joining NATO, he said, would be “most sufficient.” Read more »

Gérard Roland came to Berkeley only around the turn of this century. He grew up in Belgium, was a radical student, and after the student movements of Europe subsided, he supported himself for a time by operating trams in the city. When he was wooing his girlfriend (later wife), Heddy, she used to get a free ride in his trams. (A few years back when I visited them one summer in their villa in the Italian countryside near Lucca, Heddy told me in jest that those days she was content with a free tram ride, but now she needed a house in Tuscany to be placated). Gérard is also a good cook.

Gérard Roland came to Berkeley only around the turn of this century. He grew up in Belgium, was a radical student, and after the student movements of Europe subsided, he supported himself for a time by operating trams in the city. When he was wooing his girlfriend (later wife), Heddy, she used to get a free ride in his trams. (A few years back when I visited them one summer in their villa in the Italian countryside near Lucca, Heddy told me in jest that those days she was content with a free tram ride, but now she needed a house in Tuscany to be placated). Gérard is also a good cook.

Every hour of every day I hear the pulsating rush of le Periph and I am reminded that Paris is dead. My dorm is at the very bottom of Paris such that if the city were a ball I’d be the spot that hits the ground. I sit in my windowsill. I watch cars drive on the highway in an unending flow, like blood in veins, fish in streams, but they’re all metal idols of life. Life does not go this fast. Life stops to take a rest.

Every hour of every day I hear the pulsating rush of le Periph and I am reminded that Paris is dead. My dorm is at the very bottom of Paris such that if the city were a ball I’d be the spot that hits the ground. I sit in my windowsill. I watch cars drive on the highway in an unending flow, like blood in veins, fish in streams, but they’re all metal idols of life. Life does not go this fast. Life stops to take a rest. Sughra Raza. Color Burst, Costa Rica 2003.

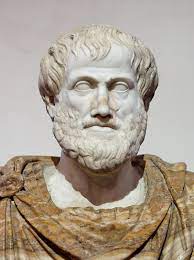

Sughra Raza. Color Burst, Costa Rica 2003. For many of the ancient philosophers that we still read today, philosophy was not only an intellectual pursuit but a way of life, a rigorous pursuit of wisdom that can guide us through the difficult decisions and battle for self-control that characterize a human life. That view of philosophy as a practical guide faded throughout much of modern history as the idea of a “way of life” was deemed a matter of personal preference and philosophical ethics became a study of how we justify right action. But with the recognition that philosophy might speak to broader concerns than those that get a hearing in academia, this idea of philosophy as a way of life

For many of the ancient philosophers that we still read today, philosophy was not only an intellectual pursuit but a way of life, a rigorous pursuit of wisdom that can guide us through the difficult decisions and battle for self-control that characterize a human life. That view of philosophy as a practical guide faded throughout much of modern history as the idea of a “way of life” was deemed a matter of personal preference and philosophical ethics became a study of how we justify right action. But with the recognition that philosophy might speak to broader concerns than those that get a hearing in academia, this idea of philosophy as a way of life