by Nicola Sayers

I am a modern-day scrapbooker. Which is to say that, like scrapbookers and notebook keepers across the ages, I am incessantly recording: things I have read, things I want to read, ideas I have come across or had, ways I want to be or to look, memorabilia from places I have been or want to go, inspiring or thought-provoking words, song lyrics, images, film clips, you name it. Like those who went before me, I record things in physical notebooks, but – and this is the new thing – my canvas is far larger than this original form. Digital photo albums, the iPhone ‘notes’ pad, emails to self, Pinterest, Instagram (but not Facebook, which lacks Instagram’s curatorial function): these are all avenues through which a fanatical need to record is fed.

I am a modern-day scrapbooker. Which is to say that, like scrapbookers and notebook keepers across the ages, I am incessantly recording: things I have read, things I want to read, ideas I have come across or had, ways I want to be or to look, memorabilia from places I have been or want to go, inspiring or thought-provoking words, song lyrics, images, film clips, you name it. Like those who went before me, I record things in physical notebooks, but – and this is the new thing – my canvas is far larger than this original form. Digital photo albums, the iPhone ‘notes’ pad, emails to self, Pinterest, Instagram (but not Facebook, which lacks Instagram’s curatorial function): these are all avenues through which a fanatical need to record is fed.

There are similarities between us twenty-first century scrapbookers and our forerunners. Walter Benjamin viewed the collector — and what is the scrapbooker if not a collector of memories, ideas, images? — as a kind of revolutionary. By taking things out of their old contexts, and repurposing them according to a new, personal, logic, the collector achieves a kind of renewal of the old world. But there is nonetheless an anxiety underlying the scrapbooker’s work. As Benjamin writes in The Arcades Project, the collector is ‘struck by the confusion, by the scatter, in which the things of the world are found.’ Like our predecessors, we digital scrapbookers, are driven – in our desire to record and to organize – by a kind of existential urgency: an impossible desire to capture the ephemeral, to articulate the ineffable. And like them, we too cling to the touchingly grandiose sense that somehow, via our paltry efforts, existence itself might be single-handedly sewn together into a meaningful pattern. The underlying fear of all scrapbookers, though, is not only the disorder and transience of existence, but the disorder and transience of the self. The unspoken mantra: I record, therefore I am. Read more »

I used to sit in class with songs in my head, loud enough to feel their beat in my fingertips. I used to blare Adele instead of listening to my teacher. I would sing voicelessly with Hozier while my classmates read a paragraph out loud. Passenger, P!nk, The Lumineers, Steven Sondheim. Billie Eilish, too, though not openly as it’s not cool to like anything that’s cool.

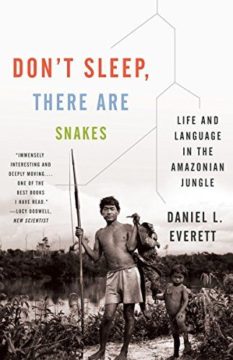

I used to sit in class with songs in my head, loud enough to feel their beat in my fingertips. I used to blare Adele instead of listening to my teacher. I would sing voicelessly with Hozier while my classmates read a paragraph out loud. Passenger, P!nk, The Lumineers, Steven Sondheim. Billie Eilish, too, though not openly as it’s not cool to like anything that’s cool. Daniel Everett’s 2008 book Don’t Sleep: There are Snakes tells two stories of loss. First, it tells how the young missionary linguist, who had been trained to analyse languages at the Summer Institute (now

Daniel Everett’s 2008 book Don’t Sleep: There are Snakes tells two stories of loss. First, it tells how the young missionary linguist, who had been trained to analyse languages at the Summer Institute (now

Most of us were in deep admiration of my DSE colleague Sukhamoy Chakravarty (I used to call him Sukhamoy-da). He was a prodigious scholar, a voracious reader of books (when discussing a book it was not unusual for him to point out to us that the author had slightly changed his position on an issue in question in the third edition in a long footnote), a man of wide intellectual interests, but also a man of charming simplicity and other-worldliness. In my period at DSE as he was mostly in the Planning Commission, I’d occasionally meet him at his home (or at Mrinal’s) in the evenings. I remember one evening I was discussing something with him in his living room, while a whole army of children (his daughter and her neighborhood friends) were enthusiastically carrying books, shifting them from one room to another corner of the house under the general supervision of his wife, Lalita (his partner and fellow economist since their Presidency College days). At one point he digressed from what we were discussing, and pointed to the army of load-carrying children, and said, “You see this is how the Industrial Revolution came about, on the backs of child labor”.

Most of us were in deep admiration of my DSE colleague Sukhamoy Chakravarty (I used to call him Sukhamoy-da). He was a prodigious scholar, a voracious reader of books (when discussing a book it was not unusual for him to point out to us that the author had slightly changed his position on an issue in question in the third edition in a long footnote), a man of wide intellectual interests, but also a man of charming simplicity and other-worldliness. In my period at DSE as he was mostly in the Planning Commission, I’d occasionally meet him at his home (or at Mrinal’s) in the evenings. I remember one evening I was discussing something with him in his living room, while a whole army of children (his daughter and her neighborhood friends) were enthusiastically carrying books, shifting them from one room to another corner of the house under the general supervision of his wife, Lalita (his partner and fellow economist since their Presidency College days). At one point he digressed from what we were discussing, and pointed to the army of load-carrying children, and said, “You see this is how the Industrial Revolution came about, on the backs of child labor”. Lots of things don’t exist. Bigfoot, a planet between Uranus and Neptune, yummy gravel, plays written by Immanuel Kant, the pile of hiking shoes stacked on your head — so many things, all of them not existing. Maybe there are more things that don’t exist than we have names for. After all, there are more real objects than we have names for. No one has named every individual squid, nor every rock on Mars, nor every dream you’ve ever had. The list of existing things consists mostly of nameless objects, it seems.

Lots of things don’t exist. Bigfoot, a planet between Uranus and Neptune, yummy gravel, plays written by Immanuel Kant, the pile of hiking shoes stacked on your head — so many things, all of them not existing. Maybe there are more things that don’t exist than we have names for. After all, there are more real objects than we have names for. No one has named every individual squid, nor every rock on Mars, nor every dream you’ve ever had. The list of existing things consists mostly of nameless objects, it seems.

A couple of weeks ago, the main healthcare provider in my city sent me a newsletter. One of the items was a brief blurb about how laughter is good for you, with a link to “Learn More About the Benefits of Laughter.” No! If you think laughter is good for our health, link to a video of a cat riding a Roomba or bear cubs on a hammock. I might click through to see those; I might even laugh. I’m not going to look at an article about the benefits of laughter, because it will become another open tab, a nagging chore, an obligation that stands between me and the conditions for laughter.

A couple of weeks ago, the main healthcare provider in my city sent me a newsletter. One of the items was a brief blurb about how laughter is good for you, with a link to “Learn More About the Benefits of Laughter.” No! If you think laughter is good for our health, link to a video of a cat riding a Roomba or bear cubs on a hammock. I might click through to see those; I might even laugh. I’m not going to look at an article about the benefits of laughter, because it will become another open tab, a nagging chore, an obligation that stands between me and the conditions for laughter. Sughra Raza. Mood … , Our Pale Blue Dot.

Sughra Raza. Mood … , Our Pale Blue Dot.