by David Oates

Full of good cheer – when does walking not perk me up? – on a too-cool March morning, past houses nicer than mine by several hundred grand with wide verandahs and Craftsman gables, and through a deep urban forest of elms, I make my way towards church.

Church!

Not exactly my normal behavior – not for lo these many decades since achieving my apostasy, my ex-Baptist-ness, and then at length making peace with it. I carried no axe to grind. Though I walked right past a low-slung building with a sign reading – no kidding! – “Chinese Baptist Church.”

I’ll return to that. But today my destination is yet more exotic, you could say, though just one more block away. “St. Sharbel Catholic Church, Maronite Rite” it proclaims itself. Whatever that might mean. My mission was to find out by attending the eleven-o’clock service.

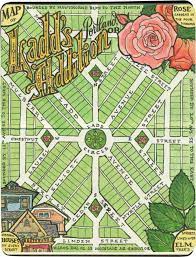

This neighborhood, which I live right next to though not quite in – seems oddly attractive to churches. One of the oldest planned developments in the western US, called “Ladd’s Addition” after its 1891 developer, former mayor William S. Ladd, it forms a square just a half-mile on a side, yet is studded with temples and houses of worship, sanctuaries grand or cozy, surprising or predictable . . . so many varieties of religious belief, so many flavors and even hues. Even in ethnically-challenged Portland.

To what end? Serving what need or what god (or gods)? Who can say. Answer: Me. Or I can try, anyway.

For I find I’m always interested, no matter how many times I pass them by on daily walks, no matter how many Sunday mornings (or other worshipful times unknown to me) I may choose to sleep in or go for hikes or burrow into my writing life as if there were no Sabbath . . . always I notice myself noticing as I walk by, in the back-mind where feelings bubble up and ask for some kind of meaningful order. . . .

Always I think about it. What I am missing/not-missing-at-all-thank-you? I might think about that line from Philip Larkin’s poem “Church Going”:

A serious house on serious earth it is

I’m interested in the seriousness. These structures of aspiration. The weekly bubble of time set apart. What is it, really. And why am I, fifty years after giving it all up, still drawn. Sometimes with tears in my eyes. Sometimes not.

So I have decided to make a small pilgrimage. Over the next few weeks I’ll walk by the churches and temples. Find out their histories. Go in if I’m not too abashed. I’ll try to feel what it feels like. And wonder what it means.

* * *

St. Sharbel Catholic Church is an imposing structure built of gray stonelike materials, with bell tower and pointed-arch entry. As churchy as it gets.

It faces a small diamond-shaped public rose garden defined by four neighborhood streets that pass it in a one-way traffic pattern. There are three other wee gardens, one for each compass point, woven into Ladd’s Addition in a perfectly confusing mesh of roundabouts and streets shooting off in unpredictable directions. The original 1891 design somehow blends this radial pattern with Portland’s staid street grid. Difficult to describe – the illustration will have to do. This is the neighborhood I live next to, enjoying its big old houses and big old elm trees.

It faces a small diamond-shaped public rose garden defined by four neighborhood streets that pass it in a one-way traffic pattern. There are three other wee gardens, one for each compass point, woven into Ladd’s Addition in a perfectly confusing mesh of roundabouts and streets shooting off in unpredictable directions. The original 1891 design somehow blends this radial pattern with Portland’s staid street grid. Difficult to describe – the illustration will have to do. This is the neighborhood I live next to, enjoying its big old houses and big old elm trees.

I walk across the freshly mulched rose garden, still weeks from flowering. The dark green canes and ruddy bark mulch emanate a healthy potentiality and propel me up the broad front stairs into the church, where I am greeted by a strikingly tall man called Christopher. I mention my unfamiliarity with it all, and reveal the little I have learned from St. Sharbel’s website:

Maronite spirituality, liturgy and traditions come from Antioch-Edessa, Syria as they were known in the Roman Empire at the time of Christ. The Aramaic language, used in liturgy, is the same language Jesus spoke during his earthly life and ministry.

The Maronite Church, one of the oldest churches of Catholicism, was led by Saint Maron, a priest (350-410 AD) who devotedly taught the Catholic faith, and ministered to many people with his gifts of healing and counsel. Today in the U.S.A. there are two eparchies (Dioceses) made up of about 75,000 Maronite Catholics. We are in union with Rome and are part of the one true Catholic Church.

Alas, Christopher informs me that I will not be hearing any Aramaic that day: the regular priest is out sick. I will have to return another day to hear the real deal.

What I do see: a perfectly ordinary Catholic service attended by perhaps fifty perfectly ordinary people. (What else did I expect?) A few with dark hair and beautifully darker skin, perhaps hinting at the Lebanese or Syrian connection – including what I guess may be a brother and sister of about twenty who sit in the pew ahead of me. They turn and greet me kindly when the “passing the peace” moment comes up. I’m always a bit lost in a Catholic service – the Baptists placed fewer demands on their congregants, and it can seem a bit wild to me, this whirlwind of standing, sitting, and kneeling, punctuated by sudden verbal outbursts. The laugh is on me for sure, low-church lad in the presence of ancient ritual.

What I do see: a perfectly ordinary Catholic service attended by perhaps fifty perfectly ordinary people. (What else did I expect?) A few with dark hair and beautifully darker skin, perhaps hinting at the Lebanese or Syrian connection – including what I guess may be a brother and sister of about twenty who sit in the pew ahead of me. They turn and greet me kindly when the “passing the peace” moment comes up. I’m always a bit lost in a Catholic service – the Baptists placed fewer demands on their congregants, and it can seem a bit wild to me, this whirlwind of standing, sitting, and kneeling, punctuated by sudden verbal outbursts. The laugh is on me for sure, low-church lad in the presence of ancient ritual.

Yet I was moved, Reader. Hard to account for. The singing wasn’t good, the organ a sad little electronic thing in a loft, the decor evidently a cheap make-over involving plywood faux-paneling such as one might see in a basement rumpus room. The borrowed preacher earnest but, well, at least earnest.

Yet – there we all were. In the presence, perhaps, of something greater. Or seeking it, anyway.

For every place of worship is surely designed for depth. No matter that individuals and congregations may fall short. Still the opportunity, the calling, the promise remains. More is possible, better is possible. Deep calls to deep and the human responds, hoping, ever, for nourishment. For something more than the husks, the leftovers and hearsay, the pebbles and stones of rote and dogma.

Always that hope, that possibility. All over the world, on a Sunday or a Sabbath or some other day of the week, these moments and places of aspiration.

* * *

The Maronite rite may be ancient but this church is recent, only taking over the building in 1970. (Hence the That-Seventies-Show paneling, I guess.) Before that . . . oh such an earthly tale, disruption and starting over, the spiritual mission not conferring any special destiny, just churn and change, same as all other things human. Bright hopeful starts and hallelujahs; then peterings-out and sighs. For “time and chance happeneth to them all” as my favorite Preacher puts it.

The church, designed primarily in the Gothic Revival style by Alfred H. Faber, was built in 1909 under the name First United Evangelical Church . . . . [which] occupied the church until 1930, when it was renamed the Cornerstone Church under a new congregation. It was later changed again to the Bethel Missionary Temple, followed by the current Maronite congregation.

Four new starts in sixty-one years. Four versions of God. And, in this neighborhood, surrounded by so many other versions, too.

* * *

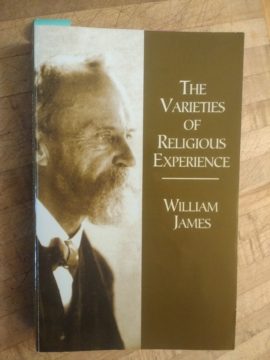

William James predicates his celebrated book The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902) upon the observation that humans seem to intuit some not-quite-seeable force or personality at work in the world: “the belief that there is an unseen order, and that our supreme good lies in harmoniously adjusting ourselves thereto.”

William James predicates his celebrated book The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902) upon the observation that humans seem to intuit some not-quite-seeable force or personality at work in the world: “the belief that there is an unseen order, and that our supreme good lies in harmoniously adjusting ourselves thereto.”

“It is as if there were in the human consciousness a sense of reality, a feeling of objective presence, a perception of what we may call ‘something there’. . . . (emphasis in original)

James likens it to that sense of “someone is the room” that might be experienced – even when someone isn’t. I think of something like what’s called “facial vision,” a kind of seeing when there is no light. Humans have had this sense that there is “something there” for a long time. A leading, an intuition.

Perhaps a pilgrimage is a question: “Who’s there?! What’s there?” I suppose we are all groping for that unseen order. Hoping for some deeper foundation of justice and love.

* * *

It is two days later. Crocuses have appeared in Ladd’s Addition, holding their tiny lavender heads proudly just a few inches above the grass. Elms tower above them as if defining a plant’s idea of heaven. (I’ve taken the long way ‘round just to walk here, so perhaps it’s my idea too.) My destination sits near another rose-garden roundabout: a diminutive structure like a child’s drawing of a church. It has an abbreviated turret instead of a steeple, just enough to announce itself. It is more tall than wide. It sits as a small, oddly vertical house beside other small houses.

I knew it (by signage) as “Portland Deaf Church” when I moved to Portland in the nineties. But soon after, it was remodeled and sold as a private home. I snuck in during the construction to see its little sanctuary, the altar-end stripped of accoutrements, the afternoon light streaming in almost sentimentally.

I knew it (by signage) as “Portland Deaf Church” when I moved to Portland in the nineties. But soon after, it was remodeled and sold as a private home. I snuck in during the construction to see its little sanctuary, the altar-end stripped of accoutrements, the afternoon light streaming in almost sentimentally.

A plaque on the foundation reveals it to have been built in 1925 as “First Italian Presbyterian Church.” It’s on the National Register of Historic Places. Our neighborhood – not just Ladd’s Addition but this whole inner-southeast part of Portland – has an Italian-immigrant echo. I have a neighbor from one of the old Italian families and she confirms that the big, highly visible Catholic church St. Philip Neri (on the opposite edge of the neighborhood from St. Sharbel) was community headquarters for many of these families.

Still is, I suppose.

So it’s not hard to imagine a bit of all-too-human drama around this self-declared “Italian Presbyterian” counterstatement. The historian Vincenza Scarpaci mentions a subtle competition among the Protestants for Italian newcomers in the late nineteenth century.

* * *

The phenomenon of repurposing sacred structures as domestic space – does it surprise you, too? Just in this little scrap of Portland there are two such decommissioned churches. So before the end of the week I have sought out the second one, literally across the street from that imposing St. Philip Neri. It’s a Methodist church turned into what real-estate jargon calls a “fourplex.” The National Register lists this building too.

The plaque in front of the residence explains:

The plaque in front of the residence explains:

The Mizpah Presbyterian Church was built in 1902 and relocated in 1911 to its current location in Ladd’s Addition. . . . It served the Presbyterian community as a church and community center until 1961. From 1961 to 1978, the structure was rented to several other congregations . . . , each of which had a short life.

After 17 years of neglect, it was purchased by Arthur Lind in 1978 who converted it over the next two years for use as four residential units. Lind completed the design work himself, used the 20 foot pews to make railings, staircases, furniture, and accent pieces, and obtained the National Register of Historic Places designation in 1983.

A place may be built upon the rock of ages, and yet be destined for change. The irony of the ages.

* * *

I imagine a great-hearted person on this pilgrimage, someone better than me, someone unburdened with damage or able to rise above it. Who doesn’t want that. Who ever achieves it.

Perhaps this is one of the reasons for such buildings. The temples and steeple-houses, the homey inviting spaces like extra-big living rooms, the cool dark apses and colonnades of formality. All the approaches. None sufficient. All of them trying to beckon: come near, come quiet, come.

It seems to me that all worship is asymptote: a Zeno’s paradox of getting closer and closer yet never finally closing the deal.

Sometimes this is the feeling I get on a forest trail. A sense of the closeness and density of life. And its ability to stay apart from me, mysterious and inscrutable, approach how I might. I am welcomed and defeated. Rewarded and stymied. Every time.

Aging feels that way to me too. And love.

And churchgoing.

* * *

I make a little excursion two blocks outside the “Ladd’s” designation to see “The World Buddhist Preaching Association.” I’ve peeked often through the window into the lobby and seen the imposing golden Buddha there. I always wonder about the “preaching” mission, which sounds surprisingly . . . evangelical? Or perhaps I mean “earnest” (or simply “aggressive”). I suppose we’ve all been harangued by fundamentalist street-preachers trying to sell hatred by calling it God’s love. Hard to imagine a Buddhist doing so. But what do I know.

I make a little excursion two blocks outside the “Ladd’s” designation to see “The World Buddhist Preaching Association.” I’ve peeked often through the window into the lobby and seen the imposing golden Buddha there. I always wonder about the “preaching” mission, which sounds surprisingly . . . evangelical? Or perhaps I mean “earnest” (or simply “aggressive”). I suppose we’ve all been harangued by fundamentalist street-preachers trying to sell hatred by calling it God’s love. Hard to imagine a Buddhist doing so. But what do I know.

There is no website nor any explanatory signage. It’s never been open when I’ve walked past. In truth I’m content just to see it there, kitty-corner from a very Portlandy McMenamins’s pub. The contrast of strange and familiar.

Well. It’s only in what I’ve begun calling the “Greater Ladd’s” area, not part of my formal territory. Still, in its brilliant red and gold, too juicy to leave out.

* * *

Sometimes churchgoing can work – can achieve the deepening, inspiriting effect – even when it’s accompanied by nonsense and outright viciousness. Sometimes there’s an intentionality built into the very stonework that speaks despite all odds.

(If you think about it, what other opportunity for truth could there even be in human affairs, except a truth that can speak over the frailties and mistakes?)

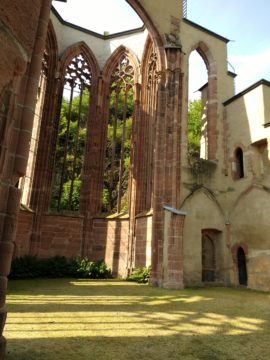

In Germany a couple years ago, walking up from the Rhine River on a too-warm summer day. Finding some leftover Gothic arches, standing, spanning, intersecting . . . over grass and gravel. The roofs gone. The walls mostly gone. The floor gone.

Sandstone arches, reddish or pink. No glass left of course, just openings divided and divided again by fluted stonework.

Sandstone arches, reddish or pink. No glass left of course, just openings divided and divided again by fluted stonework.

Through them a view of the placid Rhine and its opposite hillsides to the east. Grape-vineyards, another village. Another tourist boat chugging upriver. Sunshine, a breeze, peacefulness in this place of once-upon-a-time piety, an important medieval pilgrimage site. Then and now, probably good for business down below in Bacharach, where we will stay one night and then leave. How many thousands or tens of thousands have stood here and listened and prayed?

We felt it, my partner and I. We drank in the quiet, the traditional melancholy of ruins and also the strange elation of shattered devotions, of gods left out in the rain, of hopes-and-prayers long gone. Our secular hearts were lifted too. I own it. I feel it again, typing these words.

Medieval pilgrims came here beginning in 1289. The chapel was destroyed by war in 1689, leaving these ruins. It was called the Werner Chapel – Wernerkapelle – after a murdered boy named Werner. The horrid legend said that the Jews had killed him to use his blood in supposed rituals.

Can you imagine the stupidity, the hideous ignorant bloody-mindedness?

Yet I tell you: all the bigotry has been washed out of these ruins. What’s left is the residue of some deeper intent. That thing that calls to us despite our worst selves (that is, despite our selves).

I’m an American, a westerner. What part of my home territory has not been drenched in the bloodletting of Indian peoples? How shall I take in the vistas, accept the gift of the earth itself, this stupendously beauteous planet – without both acknowledging, and then somehow getting past, the deeds of history? It is not a formula of romantic nonsense, nor one of whitewashing the past. To love our high mountains, our Sierras, as I have loved them with decades-long intensity, mile by mile and year by year – is to admit this history of death. The Maidu, the Miwok, the Yokuts, the Paiute, removed by violence fast and violence slow.

To love these mountains is to accept history and also to stand beyond that history. To stand in the presence of earthen goodness that is deeper yet, older yet, soaked in blood of all kinds and yet still giving forth fresh beauty and health in every future second of existence.

What pilgrimage can work at all except in this way? What land – what religion, what pilgrim – is not soaked in blood and error? Earth and time must cleanse all. Will cleanse all, if the heart be open.

* * *

It is surely part of our humanity, to consider seriously this fate – that we are always entangled in history as well as aspiration. I suppose that is why, for so many years now, I have kept

Philip Larkin’s poem “Church Going” in the back of my mind. Here is its concluding stanza:

A serious house on serious earth it is,

In whose blent air all our compulsions meet,

Are recognized, and robed as destinies.

And that much never can be obsolete,

Since someone will forever be surprising

A hunger in himself to be more serious,

And gravitating with it to this ground,

Which, he once heard, was proper to grow wise in,

If only that so many dead lie round.

I love this poem. Yet it got me into trouble with one of my other literary heroes, the beloved novelist Ursula K. Le Guin – longtime resident of Portland (who passed away in 2018).

I was attending a biennial get-together of a writers group called the Blue River Gathering. There were maybe thirty of us, nestled into a lodge in the forest. And Le Guin had been invited to speak to us and stay for a few days. She stood before the big stone fireplace one evening, its embers glowing, as discussion circled around freely. She was approachable.

But not someone to mess with. This was the summer of 2006, and we were all stressed to the breaking point with the dreadful war we had been entangled in by our president. He was especially loathed as the politician who made much of his “born-again” conversion at the age of forty – cementing his popularity with cultural conservatives. Yet of course this show of religiosity did nothing to stay his hand in the matter of making war, or basing it on naked lies while advocating and using torture.

In a room of liberal nature-writers, you can imagine the disdain that circulated. Richly deserved. Yet as our rancor ran toward condemning the churches and their strangely bloodthirsty Christians, Larkin’s words rang in my head. And – unwisely – I tried to say something mitigating. Something about how, despite being traduced by politics, the churches were still “serious places, on serious ground,” where something deeper was always possible. Always on the brink of carrying someone towards kindness, charity. . .

Le Guin practically barked at me. She shut me down with a look and a single sentence. I wish I could recall the exact words. My head swam and I shut up, of course. But I certainly thought: my god, this must be the first time Le Guin has ever been wrong about anything! For I was the one who had borne wounds from the evangelicals – not her. It had taken me until the age of twenty-five to make my escape, utterly necessary though it was for a gay kid. Yet how hard it was, with how many tears. For I had been a most earnest believer.

So I was perhaps a little proud of managing to rise (briefly) above my history, to take Larkins’ broader view. But her retort was reactive, angry.

I held my tongue. Anyone can have a bad moment. Le Guin’s works are full of deep thoughtfulness, utterly inspiring. And I am still a fan of churchgoing. In my way.

* * *

At last I’ve come into the biggest of Ladd’s churches, accompanied by my partner and a friend and neighbor who used to attend here. It’s just two weeks since I began my pilgrimaging, my looking and wondering and sometimes entering.

A quiet, pure sound arises from four figures at the front. They are wearing dark suits, standing where the altar would normally be, centered in this clean, deep space – a modern basilica of unadorned concrete slabs, severe yet strangely restful. Wooden roof far above pitched only slightly, with painted gold stars. Light allowed through the blank, imposing walls in tall blue slits, minimal and gorgeous.

That a song from the sixteenth century should echo here, brought by singers from Leipzig. . . that its harmonies should mesh, should bear an edge of dissonance and then resolve. . . as if they were marvels asking for meditation. As if time were real. As if we had all come from somewhere, from other places and people whose lives, too, were rich and strange.

St. Philip Neri, at one edge of Ladd’s Addition, was dedicated in 1950. This gorgeous, floating song “Time Stands Still” was published by John Dowland in 1603, the last year of Queen Elizabeth and the first of King James. There were as yet no Englishmen to sing the song in the New World – Jamestown colony was still four years off. Shakespeare may have been working on Othello. Perhaps Measure for Measure.

St. Philip Neri, at one edge of Ladd’s Addition, was dedicated in 1950. This gorgeous, floating song “Time Stands Still” was published by John Dowland in 1603, the last year of Queen Elizabeth and the first of King James. There were as yet no Englishmen to sing the song in the New World – Jamestown colony was still four years off. Shakespeare may have been working on Othello. Perhaps Measure for Measure.

I was born the same year as this church – somehow destined to hear Dowland on this day and think about comedy, tragedy, beauty. A tall crucifix at the front.

Is the mystery of beauty different from the mystery of grace? Or are they the same question?

In this little patch of Portland are seven churches or ex-churches. Seven ways to approach the seriousness, the enduring ache of aspiration. I’ll continue walking, and thinking, and report again in Part II (four weeks hence). The Chinese Baptist Church awaits, and other surprises. Other quests and questions. Will I get to hear the Aramaic?

And if I do, what will it say to me?