by Ethan Seavey

The dandelion is thousands of miles from home. It has been in America learning about the world beyond and perhaps it wants to return. It has lived thousands of sad lives. Finally after 300 years, a seed clings to an old man’s jacket as he boards a plane, and happens to land in a small patch of dirt right by the Charles de Gaulle airport; the dandelion is welcomed home graciously, and they share the stories of what has happened in its absence. They notice little differences to him. He has mutated slightly; the increased sun in America has made his petals more yellow; the lawn mowers have made him shorter; the pesticides have made him stronger. They don’t talk to him about the sun or the lawn mowers or the pesticides, though. They talk about their shared home in France.

The dandelion is thousands of miles from home. It has been in America learning about the world beyond and perhaps it wants to return. It has lived thousands of sad lives. Finally after 300 years, a seed clings to an old man’s jacket as he boards a plane, and happens to land in a small patch of dirt right by the Charles de Gaulle airport; the dandelion is welcomed home graciously, and they share the stories of what has happened in its absence. They notice little differences to him. He has mutated slightly; the increased sun in America has made his petals more yellow; the lawn mowers have made him shorter; the pesticides have made him stronger. They don’t talk to him about the sun or the lawn mowers or the pesticides, though. They talk about their shared home in France.

Tu me manques. The French have a different construction to mean “I miss you,” which more directly translates to “you are missing from me.” it’s weaker in the sense that the I is doing nothing but feeling unfulfilled in the person’s absence. English implies an active agony; French implies a passive fractured self. I think before coming abroad that I would’ve said English is more accurate to the idea of missing someone. But now I’ve lived in Paris while the man I love lived in Tel Aviv and my family lived in Chicago and Denver and LA and I find the truth is somewhere in the middle, closer to the French side. I miss /you/ are missing from me. Day to day, it’s not active. Missing lies dormant in your body and makes the day a little darker, a little colder. It makes you feel guilty for letting the pain be so tiny, so unnoticeable. But it also rushes in and drowns you some days and you feel a longing for melodrama, which is never satisfied with a text or a phone call. Read more »

Halfway through a pilgrimage, it’s a good thing to remember why you’re on it – where you hope it’s taking you. I’m following a plan to consider the strangely numerous churches of this little Portland neighborhood, just a half-mile square but crowded with varieties of religiosity.

Halfway through a pilgrimage, it’s a good thing to remember why you’re on it – where you hope it’s taking you. I’m following a plan to consider the strangely numerous churches of this little Portland neighborhood, just a half-mile square but crowded with varieties of religiosity.

In the last two decades I have been to China many times, mostly for lectures and conferences primarily in Beijing and Shanghai. Of course, compared to what I saw in my first visit in 1989, China has undergone a dramatic economic transformation. The most dazzling of commonly visible changes are in infrastructure, highways, skyscrapers, bullet trains, airports, etc. There are parts of Shanghai now, say the eye-catchingly rich Pudong district, where once coming out of my hotel for a moment I was confused if I was really anywhere near the Shanghai city I had seen before. My academic colleagues tell me that the pay scales in top universities are now almost the same as in America, in order to attract top talent back to China. Chinese airports and high-speed trains are certainly more advanced than the ones you see in most American cities. My Chinese students in Berkeley have often told me that in application of digital technology in daily life (particularly in retail trade and local transportation and communication) they are struck by how backward the US is compared to China.

In the last two decades I have been to China many times, mostly for lectures and conferences primarily in Beijing and Shanghai. Of course, compared to what I saw in my first visit in 1989, China has undergone a dramatic economic transformation. The most dazzling of commonly visible changes are in infrastructure, highways, skyscrapers, bullet trains, airports, etc. There are parts of Shanghai now, say the eye-catchingly rich Pudong district, where once coming out of my hotel for a moment I was confused if I was really anywhere near the Shanghai city I had seen before. My academic colleagues tell me that the pay scales in top universities are now almost the same as in America, in order to attract top talent back to China. Chinese airports and high-speed trains are certainly more advanced than the ones you see in most American cities. My Chinese students in Berkeley have often told me that in application of digital technology in daily life (particularly in retail trade and local transportation and communication) they are struck by how backward the US is compared to China.

Twitter is toxic, suggests autocomplete; Twitter is an echo chamber, or at best a waste of time. Twitter is a hotbed of political factionalism. Twitter can be a frightening place for people who are harassed or threatened, and it may become more so when a recently announced takeover is complete. The bullying and misinformation and political threat are all real, and they’ve been central to recent discussions about the takeover. But Twitter is a big place, and some of us are there mainly for things we love. Birds, for example, and poems.

Twitter is toxic, suggests autocomplete; Twitter is an echo chamber, or at best a waste of time. Twitter is a hotbed of political factionalism. Twitter can be a frightening place for people who are harassed or threatened, and it may become more so when a recently announced takeover is complete. The bullying and misinformation and political threat are all real, and they’ve been central to recent discussions about the takeover. But Twitter is a big place, and some of us are there mainly for things we love. Birds, for example, and poems.

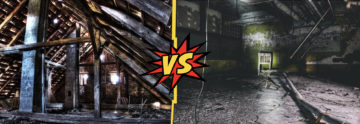

There are two kinds of people in this world: those who find basements scary and those who find attics scary. I suppose there might be some folks (bless their hearts) who are disturbed by both, like those ethereal creatures with one blue eye and one brown. I refuse to countenance the idea of people who have no feelings of unease in either space. To be that well-adjusted, that free from inchoate fear, that grounded in the solid objects of reality—I draw back in horror at the thought. We will leave these hale and pragmatic types to their smoothies and their 401Ks and godspeed to them.

There are two kinds of people in this world: those who find basements scary and those who find attics scary. I suppose there might be some folks (bless their hearts) who are disturbed by both, like those ethereal creatures with one blue eye and one brown. I refuse to countenance the idea of people who have no feelings of unease in either space. To be that well-adjusted, that free from inchoate fear, that grounded in the solid objects of reality—I draw back in horror at the thought. We will leave these hale and pragmatic types to their smoothies and their 401Ks and godspeed to them.

I find Sue Hubbard’s writings to be an invitation to feel sorrowful. And therefore a beckoning towards a search for beauty, an attempt at forgiveness and redemption and reckoning; a belief in the possibility of joy.

I find Sue Hubbard’s writings to be an invitation to feel sorrowful. And therefore a beckoning towards a search for beauty, an attempt at forgiveness and redemption and reckoning; a belief in the possibility of joy.

Friedrich Nietzsche is my “desert island philosopher.” Guests, or “castaways” on BBC Radio 4’s long running program “Desert Island Discs” are allowed to take to their desert island, in addition to eight pieces of music, a text of religious or philosophical significance. Many accept the bible as the default option. For me, the choice is a no brainer: I’d take the works of Nietzsche.

Friedrich Nietzsche is my “desert island philosopher.” Guests, or “castaways” on BBC Radio 4’s long running program “Desert Island Discs” are allowed to take to their desert island, in addition to eight pieces of music, a text of religious or philosophical significance. Many accept the bible as the default option. For me, the choice is a no brainer: I’d take the works of Nietzsche.