by Dick Edelstein

Although jazz pianist, composer, arranger and lyricist Billy Strayhorn died in 1967 at the age of 51, his obscure life has since then become much better known than it was during his lifetime. His songs remain popular, and his reputation has continued to grow. Strayhorn shares credit for many jazz tunes he composed and arranged in collaboration with Duke Ellington and contributed without credit to others, such as the popular “Satin Doll”, but none of these tunes illustrate his importance and success as a jazz composer better than “Lush Life” and “Take the A Train”. The latter not only became the theme song of the Ellington orchestra but also one of its greatest successes and an anthem of the swing era. The lyrics of this song came from notes that Strayhorn took when he came to New York to work for Ellington for the first time, when he was only 23 years old. Ellington had given him directions on the easiest way to get to his house in Harlem – by taking the A train. The song has gone on to become one of the great jazz tunes both in its version with lyrics and as an instrumental.

Let’s consider one of Strayhorn’s most popular compositions, Lush Life, recorded by dozens of jazz artists over the years, and in recent years by Lady Gaga and Queen Latifa. For many jazz fans, one of the most memorable recordings of this song is the John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman version on their album released by Impulse! in 1963, which was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2000. Most of the lyrics were written when Strayhorn was still in high school, living in Pittsburgh. In a world-weary tone, the lyrics speak of night life following a failed romance. They represent a young boy’s fantasy about a sophisticated life seen from the point of view of a jaded bon vivant. Remarkably, they also describe the sort of life that, against all odds, Strayhorn was eventually to lead. Read more »

Going back and reading one’s favorite authors is like seeing an old friend after a long absence: things fall into place, you remember why it is you get along with and like the other person, and their idiosyncrasies and unique character reappear and interact with your own, making old patterns reemerge and lighting up parts of you that have long been dormant.

Going back and reading one’s favorite authors is like seeing an old friend after a long absence: things fall into place, you remember why it is you get along with and like the other person, and their idiosyncrasies and unique character reappear and interact with your own, making old patterns reemerge and lighting up parts of you that have long been dormant. The western admirers of Amartya Sen as a public intellectual may not be aware that he is actually in a long line of globally engaged cultural elite that Bengal has produced. (This is true to some extent of the elite elsewhere in India as well, particularly around Chennai and Mumbai, but I think in sheer scale over the last two hundred years, Bengal may have a special claim). One aspect of this phenomenon is worth reflecting on. These members of the cultural elite were well-versed in the manifold offerings of the West, but they came to them with a solid grounding in the cultural wealth of India. Take Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833). He was, as Nehru describes him in his Discovery of India, “deeply versed in Indian thought and philosophy, a scholar of Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic, ..a product of the mixed Hindu-Muslim culture, …the world’s first scholar of the science of Comparative Religion.” He contributed to the development of Bengali prose. He was a social reformer in Hindu society, actively engaged in serious religious debates with Christian missionaries in India, and a champion of women’s rights and freedom of press (standing up against colonial censorship). Yet when he went to England he caused some stir as the urbane face of a reforming Indian society, was active in campaigning for the 1832 Reform Act as a step to British democracy. The philosopher Jeremy Bentham reportedly even began a campaign to elect him to the British Parliament (but Roy caught meningitis and died in Bristol soon after).

The western admirers of Amartya Sen as a public intellectual may not be aware that he is actually in a long line of globally engaged cultural elite that Bengal has produced. (This is true to some extent of the elite elsewhere in India as well, particularly around Chennai and Mumbai, but I think in sheer scale over the last two hundred years, Bengal may have a special claim). One aspect of this phenomenon is worth reflecting on. These members of the cultural elite were well-versed in the manifold offerings of the West, but they came to them with a solid grounding in the cultural wealth of India. Take Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833). He was, as Nehru describes him in his Discovery of India, “deeply versed in Indian thought and philosophy, a scholar of Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic, ..a product of the mixed Hindu-Muslim culture, …the world’s first scholar of the science of Comparative Religion.” He contributed to the development of Bengali prose. He was a social reformer in Hindu society, actively engaged in serious religious debates with Christian missionaries in India, and a champion of women’s rights and freedom of press (standing up against colonial censorship). Yet when he went to England he caused some stir as the urbane face of a reforming Indian society, was active in campaigning for the 1832 Reform Act as a step to British democracy. The philosopher Jeremy Bentham reportedly even began a campaign to elect him to the British Parliament (but Roy caught meningitis and died in Bristol soon after).

The perfect, so the saying goes, is the enemy of the good. Don’t deny yourself real progress by refusing to compromise. Be realistic. Pragmatic. Patient. Don’t waste resources and energy on lofty but ultimately unobtainable goals, no matter how noble they might be; that will only lead to frustration, and worse, hold us all back from the smaller victories we can actually achieve.

The perfect, so the saying goes, is the enemy of the good. Don’t deny yourself real progress by refusing to compromise. Be realistic. Pragmatic. Patient. Don’t waste resources and energy on lofty but ultimately unobtainable goals, no matter how noble they might be; that will only lead to frustration, and worse, hold us all back from the smaller victories we can actually achieve. My eyes traced the 1500-mile-long arc of the Aleutian Range. Running down the Alaskan Peninsula, the land on either side of the mountains is mainly wilderness and wildlife refuges. Even more astonishing was the complete absence of roads. As a Californian that is hard to fathom.

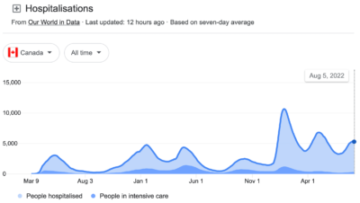

My eyes traced the 1500-mile-long arc of the Aleutian Range. Running down the Alaskan Peninsula, the land on either side of the mountains is mainly wilderness and wildlife refuges. Even more astonishing was the complete absence of roads. As a Californian that is hard to fathom. A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a

A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a

It’s 1980, I’ve just had my first proper kiss, and the newspapers are announcing the death of love.

It’s 1980, I’ve just had my first proper kiss, and the newspapers are announcing the death of love.

In June 1945, the American military appointed twenty-nine-year old Pat Lochridge mayor of Berchtesgaden, the tiny fairytale Bavarian town near the Austrian border crowded by Alps, where three thousand feet up, Hitler built his Eagle’s Nest retreat. “It is the intention of the Allies that the German people be given the opportunity to prepare for the eventual reconstruction of their life on a democratic and peaceful basis,” wrote the Allies at Potsdam.

In June 1945, the American military appointed twenty-nine-year old Pat Lochridge mayor of Berchtesgaden, the tiny fairytale Bavarian town near the Austrian border crowded by Alps, where three thousand feet up, Hitler built his Eagle’s Nest retreat. “It is the intention of the Allies that the German people be given the opportunity to prepare for the eventual reconstruction of their life on a democratic and peaceful basis,” wrote the Allies at Potsdam.