by Carol A Westbrook

We live in an artificially-colored world, filled with added color in our homes, our clothing, our toys, our hair and even our food! We take this plethora of colors for granted. By comparison, the natural world is bland and almost monotone, except for small patches of brightly colored flowers or birds.

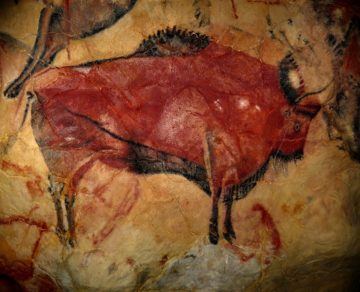

Ever since prehistoric times, man has had the urge to add color to his surroundings by expressing himself in paintings. Imagine a caveman picking up a charred piece of wood from his fire and drawing a picture on the cave wall. Later he added colors made from colored clays and stones that he picked up near the cave…and so painting begins. Some of the oldest of these ancient paintings were located deep in caves so carefully hidden that they lie undisturbed for millenia. One of the most famous of these are the paintings in the caves of Lascaux, in Southwestern France, depicting over 2,000 figures of animals and men, as shown in this detail of a bison colored with red ochres.

The Lascaux cave art was created over 17,000 years ago, using paint made from local sources.

The colored clays used to paint the cave walls were iron-containing rocks and clays known as ochres. Ochres are ubiquitous, as iron is the fifth-most abundant element in the earth. The colors of ochre stones vary from muted yellow to browns and reds; no doubt the caveman artist tried burning his colored stones and found that he created even more colors. This is due to reduction of the iron ore within the stone, resulting in the production of iron oxide or rust. The caveman’s paint colors, or his palette, included yellow ochre, red ochre, raw umber, raw Sienna and burnt Sienna. Burnt Sienna? No, this is not the name of a color derived from burning the medieval town of Sienna, but rather from burning a brown stone found near Sienna, which when burnt gives and even darker brown. Read more »

This past spring, I found myself sitting, masked, at a wooden desk among a scattering of scientific researchers at the Museo Galileo in Florence. Next to me was a thick reference book on the history of astronomical instruments and a smaller work on the sundials and other measuring devices built into the churches of Florence to mark the cyclical turning points of cosmic time. The gnomon of Santa Maria del Fiore, for instance, consisted of a bronzina, a small hole set into the lantern ninety meters above that acted as a camera oscura and projected an image of the sun onto the cathedral floor far below. At noon on the day of the solstice, the solar disc superimposed itself perfectly onto a round marble slab, not quite a yard in diameter, situated along the inlaid meridian. I studied the explanations of astronomical quadrants and astrolabes and the armilla equinoziale, the armillary sphere of Santa Maria Novella, made up of two conjoined iron rings mounted on the façade that told the time of day and year based on the position of their elliptical shadow, when all at once it occurred to me that I’d wanted to write about something else altogether, about a person I occasionally encountered, a phantom living somewhere inside me: the young woman who’d decided not to leave, not to move to Berlin after all, to rip up the letter of acceptance to the art academy she received all those years ago and to stay put, in New York. Alive somewhere, in some other iteration of being, was a parallel existence in an alternative universe, one of the infinite spheres of possibility in which I’d decided differently and become a different woman.

This past spring, I found myself sitting, masked, at a wooden desk among a scattering of scientific researchers at the Museo Galileo in Florence. Next to me was a thick reference book on the history of astronomical instruments and a smaller work on the sundials and other measuring devices built into the churches of Florence to mark the cyclical turning points of cosmic time. The gnomon of Santa Maria del Fiore, for instance, consisted of a bronzina, a small hole set into the lantern ninety meters above that acted as a camera oscura and projected an image of the sun onto the cathedral floor far below. At noon on the day of the solstice, the solar disc superimposed itself perfectly onto a round marble slab, not quite a yard in diameter, situated along the inlaid meridian. I studied the explanations of astronomical quadrants and astrolabes and the armilla equinoziale, the armillary sphere of Santa Maria Novella, made up of two conjoined iron rings mounted on the façade that told the time of day and year based on the position of their elliptical shadow, when all at once it occurred to me that I’d wanted to write about something else altogether, about a person I occasionally encountered, a phantom living somewhere inside me: the young woman who’d decided not to leave, not to move to Berlin after all, to rip up the letter of acceptance to the art academy she received all those years ago and to stay put, in New York. Alive somewhere, in some other iteration of being, was a parallel existence in an alternative universe, one of the infinite spheres of possibility in which I’d decided differently and become a different woman. Among other things London School of Economics is associated in my mind with bringing me in touch with one of the most remarkable persons I have ever met in my life, and someone who has been a dear friend over nearly four decades since then. This is Jean Drèze.

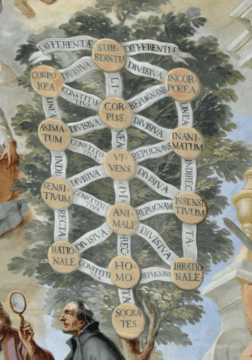

Among other things London School of Economics is associated in my mind with bringing me in touch with one of the most remarkable persons I have ever met in my life, and someone who has been a dear friend over nearly four decades since then. This is Jean Drèze. Although by no means the only ones, two models of human beings and their relation to society are prominent in modern social and political thought. At first glance they seem incompatible, but I want to sketch them out and start to establish how they might plausibly be made to fit together.

Although by no means the only ones, two models of human beings and their relation to society are prominent in modern social and political thought. At first glance they seem incompatible, but I want to sketch them out and start to establish how they might plausibly be made to fit together.

Anneliese Hager. Untitled. ca. 1940-1950

Anneliese Hager. Untitled. ca. 1940-1950

“

“ Francis Fukuyama does not mind having to play defense. Recognizing that the problems plaguing liberal societies result in no small part from the flaws and weaknesses of liberalism itself, he argues in Liberalism and its Discontents (Profile Books: 2022) that the response to these problems, all said and done, is liberalism. This requires some courage: three decades ago, Fukuyama may have captured the spirit of the age, but the spirit has grown impatient with liberalism as of late. Fukuyama, however, does not think of it as a worn-out ideal. He has taken note of right-wing assaults, as well as progressive criticisms that suggest a need to go beyond it; and his verdict is that any attempt at improvement will either stay in a liberal orbit or lead to political decay. Liberalism is still the best we have got.

Francis Fukuyama does not mind having to play defense. Recognizing that the problems plaguing liberal societies result in no small part from the flaws and weaknesses of liberalism itself, he argues in Liberalism and its Discontents (Profile Books: 2022) that the response to these problems, all said and done, is liberalism. This requires some courage: three decades ago, Fukuyama may have captured the spirit of the age, but the spirit has grown impatient with liberalism as of late. Fukuyama, however, does not think of it as a worn-out ideal. He has taken note of right-wing assaults, as well as progressive criticisms that suggest a need to go beyond it; and his verdict is that any attempt at improvement will either stay in a liberal orbit or lead to political decay. Liberalism is still the best we have got. Every now and then, a nation becomes modern. Greeks and Poles and Russians were modern, for a time. Now it’s the Ukrainians’ turn.

Every now and then, a nation becomes modern. Greeks and Poles and Russians were modern, for a time. Now it’s the Ukrainians’ turn.