by Michael Liss

Gentlemen, I’m putting the two of you on the hot seat with me. I want that third alternative!

—Captain James T. Kirk, USS Enterprise, Stardate 3289.8

Donald Trump and Joe Biden. Ron DeSantis and Biden. Trump and Kamala Harris. DeSantis and Amy Klobuchar. Ron Scott and Elizabeth Warren. Greg Abbott and Pete Buttigieg. Ted Cruz and Liz Cheney (wait, what?).

Tired of the same old headlines, the same ideas, the same enmities? Looking for something better? Captain Kirk’s Hobson’s Choice merely involved the lives of several million. We have a hundred times as many.

Don’t we all want that third alternative? Pew Research released a poll on August 9, which, among other things, tested that assumption, and the answer is a qualified maybe—“a sizable minority of Americans are supportive of the idea of having a greater choice of parties.” When you get closer to the numbers you find the greatest support comes from Independents (roughly half) and the least (21%) from Republicans (also, not surprisingly). But what you also see is a generational divide. Those in the younger age cohorts are twice as likely to want a third party than those over 65.

I’ll ask again: Do you want that Third Alternative? Andrew Yang (age 47), David Jolley (49), and Christine Todd Whitman (75) think you do. They have founded a new political party called “Forward,” which, presumably, is interested in moving forward.

Can they be successful? Let’s hedge our bets and say it depends on your metrics. Third parties emerge for several reasons. The first is simply decay-related—some just die off. Our earliest organized political party, the Federalists, elected John Adams in 1796, but never won another Presidential election thereafter.

The second relates to some political parties’ internal dynamics. By 1824, Jefferson’s then-dominant Democratic-Republican Party, which had won the prior six Presidential elections, could no longer hold the ambitions of its leading lights nor manage increasingly potent regional issues. Four credentialed candidates emerged: John Quincy Adams, the war hero Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay of Kentucky, and William Crawford of Georgia, who had been a Senator, Secretary of War and of the Treasury, and Ambassador to France. The result was incoherent—Jackson got the most popular and Electoral votes, but all four men performed credibly enough, and the election went to the House of Representatives. There, after some possibly corrupt wheeling and dealing, Adams emerged as President, Henry Clay as Secretary of State, and Andrew Jackson (and his followers) as very angry men. That blew apart the Democratic-Republicans, with the (minority, pro-Adams) wing becoming, for a time, the “National Republican Party” (later the Whigs) and the majority the “Jacksonian Democrats,” the antecedent of today’s Democratic Party.

The third has elements of the first two: Parties that run out of ideas and are riven by internal disputes. The Whigs divorced themselves from Jacksonian Democrats, but carried over into the new party the virus of North-South disagreements. They elected two Presidents in the 1840s, William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor, but neither lived out their terms. Harrison’s successor, John Tyler, was so “un-Whig” (presumably, the first “WINO”) that they nominated Henry Clay, by then a Whig, in 1844—he lost, again. Millard Filmore, who served out the balance of Taylor’s term, successfully managed the intricate negotiations over the Compromise of 1850, and was rewarded by his party by…their nominating Winfield Scott in 1852. Apparently, the supply of viable Whig ideas on the most critical issues before the country was less than the number of Whig Generals as potential candidates. The party dissolved after Scott’s convincing defeat and difficult and angry debates over the Missouri Compromise. Some displaced Whigs became Free-Soilers; some became Know-Nothings; and, in the most important movement, much of the best of their talent became newly minted Republicans.

Having three major parties blow up in the years between 1796 and 1854 gives you a sense that our American Experiment was still a little experimental. In fact, if you look at elections between 1824 and 1864, what you see is a far larger number of distinguished candidates than places to put them. America had talent.

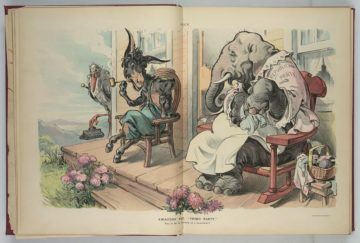

1860 was a watershed election—four serious men, all occupying different parts of the political “space,” and with a result that solidified a two-party system for the future. Ever since 1860, while there have been third-party candidacies, none have been successful at the Presidential level. Putting aside the doomed-to-fail candidacies of the Socialist Party (six elections, four with Eugene V. Debs, none with Electoral Votes), the frequency of third-party candidacies began to decline, and their nature became different.

There have been 40 Presidential elections since 1860. Excluding the exhilaratingly bizarre 1912 contest and the fascinating 1968 Election (each of which merits, and will get, a paragraph or two of their own below), meaningful third-party participation (by my definition, at least 5% of the popular vote or winning a state’s Electoral Votes) has occurred only four times. In 1892, James Weaver of the Populist Party won 8.5% of the popular vote and 22 Electoral Votes. In 1924, the great Robert LaFollette of the Progressive Party took 16.6% of the vote (and his home state of Wisconsin) in a GOP/Coolidge landslide. In 1948, an angry South, unhappy that Truman supported integration in the Army, gave four states and 39 Electoral Votes to Strom Thurmond’s segregationist Dixiecrats. Thurmond got only 2.4% of the popular vote, but was hoping to throw the election into the House of Representatives, and there to bargain for a hands-off policy in return for his four states’ support. In 1980, a Republican Congressman from Illinois, John Anderson, kicked off a quixotic campaign as a true moderate. Early polling showed him in the low 20s, but structural disadvantages and some campaign mishaps had “The Anderson Difference” at 6.6% on Election Day. Most recently, Ross Perot ran in 1992 and 1996, getting 18.9 and then 8.4%, but winning no states. The ideas these candidacies represented might have been of interest, but the candidates themselves had no realistic chance of success.

That leaves me with my two favorites, 1912 and 1968, each for their own reasons and each with its own resonance.

In 1912, Teddy Roosevelt, angered that his (former) friend, protégé, and successor, William Howard Taft was not continuing in TR’s ideological footsteps, decided he wanted his old job back. In running for reelection in 1904, TR had promised not to violate the unwritten “George Washington” rule of a two-term maximum, but it was awfully boring being an ex-President, and Taft was just too much of a conservative for TR’s tastes. Besides, Taft didn’t even want the job—he wanted to be a Supreme Court Justice, so who better than TR to restore a rightful path for the country?

Roosevelt’s problem is that, while Taft might have ached to wear the black robe, he was also possessed of a certain self-esteem and wasn’t inclined to step aside. Perhaps not so curiously, a lot of Republican insiders preferred the placid traditionalist Taft to the mercurial TR. At the Republican Convention, TR’s challenge fell short. Taft won renomination and TR walked out…and founded the Progressive (Bull Moose) Party.

Roosevelt had lost none of his personal vitality or his ability to stir up a crowd. It was a great, exciting campaign, punctuated by him being shot at a Bull Moose rally, but finishing his speech before going off for treatment. It was also a disaster for the Republicans—regardless of TR’s personal appeal, many of the party regulars were “regular” and either preferred Taft for his lower-volume approach or followed leadership. In the end, Taft and TR split the GOP and made for an Electoral College landslide for Woodrow Wilson. With apologies to Al Gore (and a glare at Ralph Nader), the 1912 election is probably the only one where a third-party candidacy was truly decisive. It’s impossible to say with certainty that Taft would have beaten Wilson in a head-to-head, but it’s certain he couldn’t while spitting support with Roosevelt.

Finally, let’s talk about one of the most impactful but under-the-radar Third Party candidacies ever, George Wallace’s run in 1968. The 1968 campaign itself is worth several books for its twists and turns, starting with LBJ’s decision not to run after a tough New Hampshire primary, the return of Richard Nixon, the tragedies of the assassination of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy, and the bizarre and violent Democratic National Convention. But it’s Wallace’s approach that was fascinating, because beyond the segregationist, overtly racist language that helped him carry Louisiana, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Alabama, he added an element that Strom Thurmond had left behind in 1948—economic and social populism. Wallace didn’t just talk about race in the abstract, he framed part of it in crime and loss of economic opportunity for the (white) working man. The (liberal) elites, educated in Ivy League schools, living in exclusive communities where they didn’t have to worry about basic services, and freed from day-to-day economic concerns like factory closings and layoffs, sneered at the mere worker, while imposing on them their social values. A Wallace Presidency would be beholden to neither the Democrats nor Republicans—it would work for those patriotic Americans who had unjustly been left behind.

There was a path for Wallace—a tight one that would have probably ending up pushing the election to the House of Representatives—but the pure volatility of the moment, especially in the spring and early summer, when he was polling in the low 20s, cities were burning, and the Democrats were self-immolating, made it possible.

In the end, an equilibrium reestablished itself, and Wallace’s campaign weakened through the fall. The unions lined up behind Humphrey, and HHH began to find his own voice, independent of LBJ’s. Liberal Democrats began to “return home.” As for Nixon, his own law-and-order rhetoric, coupled with not-so-subtle hints that a vote for Wallace would help the far more liberal Humphrey, helped bleed Wallace’s support in the South and border states, and that was probably decisive.

Still, on Election Day, on top of the Deep South states that Wallace won outright, he got 13.5% of the vote nationwide. Out of the South, Wallace got 10% or more of the popular vote in places like Maryland, Michigan, and Ohio, over 9% in New Jersey, 8.5% in Illinois, and more than 11% in closely contested Missouri. Something was clearly going on at a tectonic level. Wallace was defiantly not speaking to the entire nation, but he was resonating with a significant portion of it.

We would be blind not to recognize that it’s an approach that still has relevance. And we would be blind not to realize that candidacies like Wallace’s, or LaFollette’s, or even Perot’s arise out of needs that are not being met. When the number of people with unmet needs reaches a critical mass, it must find an outlet. Sometimes that can be a positive development, other times deeply corrosive to the health of our democracy. It’s up to us to decide whether we care enough to work on it.

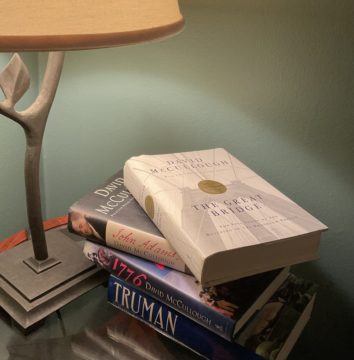

I want to stop here and insert a personal note. Last week, the popular historian David McCullough passed away. Some people know him from his narration of Ken Burns “The Civil War” or his years on “The American Experience.” Almost all of us have at least one or two of his books. I have six, most of them given to me as gifts. McCullough was controversial among professional historians because he wasn’t one: he was an English major at Yale and, while he dug deeply into the material he was researching, he wrote for the public and not for professionals. He carried with him a sunny and optimistic view of the country. Maybe it was too sunny and did not tell the entire story, but to read a McCullough book is to get a sense of both civic pride and civic duty.

I want to stop here and insert a personal note. Last week, the popular historian David McCullough passed away. Some people know him from his narration of Ken Burns “The Civil War” or his years on “The American Experience.” Almost all of us have at least one or two of his books. I have six, most of them given to me as gifts. McCullough was controversial among professional historians because he wasn’t one: he was an English major at Yale and, while he dug deeply into the material he was researching, he wrote for the public and not for professionals. He carried with him a sunny and optimistic view of the country. Maybe it was too sunny and did not tell the entire story, but to read a McCullough book is to get a sense of both civic pride and civic duty.

I thought of that this last Saturday as I ran New York City’s “Summer Streets,” which closes most of Park Avenue to cars and opens a pathway south to the Brooklyn Bridge. It was a bright and beautiful day, not too hot or humid, perfect for an old guy who wanted to make the roughly six-mile route all the way to the Brooklyn side of the bridge. The wooden walkway was crowded as always, but opened up after I passed the Manhattan-side span. I kept going, planted my feet on Brooklyn soil (or concrete), turned, and, depending on human traffic, ran/trotted/walked my way back. In the harbor was the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. A modest stroll would get you to Trinity Church, a bit farther to Federal Hall, where George Washington took the Oath of Office, and to Fraunces Tavern, where he said goodbye to his officers. History, our history, was right here.

In the epilogue to his The Great Bridge, McCullough wrote:

With normal maintenance, the engineers say, the bridge will last another hundred years. If parts are replaced from time to time, even entire cables if necessary—which would be perfectly possible—then, ‘As far as we are concerned, it will last forever.’

Proper maintenance, and it could last forever. We don’t need a third party to recognize the wisdom of that.