by Eric Bies

There was a time when Google replied with images of and information about a world-class jockey, an Englishman born the same year Mark Twain published The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Lately, the results of the same query tend toward the man of our time, the subject of this interview. Call it a correction: Steve Donoghue the Boston book critic, Steve Donoghue the editor, Steve Donoghue the YouTuber.

There was a time when Google replied with images of and information about a world-class jockey, an Englishman born the same year Mark Twain published The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Lately, the results of the same query tend toward the man of our time, the subject of this interview. Call it a correction: Steve Donoghue the Boston book critic, Steve Donoghue the editor, Steve Donoghue the YouTuber.

His bylines regularly straddle Books columns at venues large (The Christian Science Monitor, The Washington Post, The National) and small (Big Canoe News, The Bedford Times Press). He is a co-founder of Open Letters Review (where his annual end-of-year Best and Worst Books wrap-ups shouldn’t be missed). His work has been selected to appear at this very site. He reads faster and probably writes faster than you and me combined, and the proof is in the literary pudding: literally thousands of book reviews, articles, and essays to his name. “Prodigious industry” does not begin to tell the story; it’s his unconventional YouTube presence that registers a note of head-scratching astonishment.

For starters, not a single one of his videos has come close to going viral. His second most popular upload, “The Only Sure-Fire Way to Deal with Book-Mildew”—a parody of book restoration guides, instructing anxious owners of moldy tomes to shower the offending objects with water, then throw them away—boasts just 18,000 views. (And that’s an outlier: the typical Donoghue upload tends to clock in at around 850.) His subscriber count, by most measures modest, weighs in at 13,600. And yet stacked against this figure is the rather remarkable channel-wide tally of 5.7 million video views. Rain or shine, that number climbs at a steady rate of 20,000 new views per week. Read more »

This year marks the 42nd anniversary of the American release of The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy. Douglas Adams’ “five-book trilogy,” of which Hitchhiker’s was the first installment, led readers through a melancholy universe in which bureaucracy is the ultimate source of evil and shallow, self-serving incompetents are the galaxy’s greatest villains. The best-selling series helped shape the worldview of Generation X, capturing the nihilistic cynicism of the Thatcher/Reagan 1980s.

This year marks the 42nd anniversary of the American release of The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy. Douglas Adams’ “five-book trilogy,” of which Hitchhiker’s was the first installment, led readers through a melancholy universe in which bureaucracy is the ultimate source of evil and shallow, self-serving incompetents are the galaxy’s greatest villains. The best-selling series helped shape the worldview of Generation X, capturing the nihilistic cynicism of the Thatcher/Reagan 1980s.

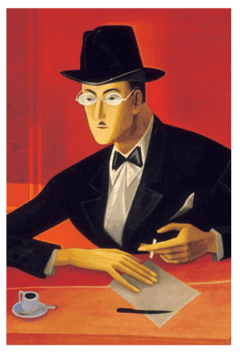

Senhor Soares goes on to explain that in his job as assistant bookkeeper in the city of Lisbon, when he finds himself “between two ledger entries,” he has visions of escaping, visiting the grand promenades of impossible parks, meeting resplendent kings, and traveling over non-existent landscapes. He doesn’t mind his monotonous job, so long as he has the occasional moment to indulge in his daydreams. And the value for him in these daydreams is that they are

Senhor Soares goes on to explain that in his job as assistant bookkeeper in the city of Lisbon, when he finds himself “between two ledger entries,” he has visions of escaping, visiting the grand promenades of impossible parks, meeting resplendent kings, and traveling over non-existent landscapes. He doesn’t mind his monotonous job, so long as he has the occasional moment to indulge in his daydreams. And the value for him in these daydreams is that they are

Sughra Raza. Chughtai In Shabnam’s Living Room, November, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Chughtai In Shabnam’s Living Room, November, 2022.

I moved to Berlin in 1984, but have rarely written about my experiences living in a foreign country; now that I think about it, it occurs to me that I lived here as though in exile those first few years, or rather as though I’d been banished, as though it hadn’t been my own free will to leave New York. It’s difficult to speak of the time before the Wall fell without falling into cliché—difficult to talk about the perception non-Germans had of the city, for decades, because in spite of the fascination Berlin inspired, it was steeped in the memory of industrialized murder and lingering fear and provoked a loathing that was, for some, quite visceral. Most of my earliest friends were foreigners, like myself; our fathers had served in World War II and were uncomfortable that their children had wound up in former enemy territory, but my Israeli and other Jewish friends had done the unthinkable: they’d moved to the land that had nearly extinguished them, learned to speak in the harsh consonants of the dreaded language, and betrayed their family and its unspeakable sufferings, or so their parents claimed. We were drawn to the stark reality of a walled-in, heavily guarded political enclave, long before the reunited German capital became an international magnet for start-ups and so-called creatives. We were the generation that had to justify itself for being here. It was hard not to be haunted by the city’s past, not to wonder how much of the human insanity that had taken place here was somehow imbedded in the soil—or if place is a thing entirely indifferent to us, the Earth entirely indifferent to the blood spilled on its battlegrounds.

I moved to Berlin in 1984, but have rarely written about my experiences living in a foreign country; now that I think about it, it occurs to me that I lived here as though in exile those first few years, or rather as though I’d been banished, as though it hadn’t been my own free will to leave New York. It’s difficult to speak of the time before the Wall fell without falling into cliché—difficult to talk about the perception non-Germans had of the city, for decades, because in spite of the fascination Berlin inspired, it was steeped in the memory of industrialized murder and lingering fear and provoked a loathing that was, for some, quite visceral. Most of my earliest friends were foreigners, like myself; our fathers had served in World War II and were uncomfortable that their children had wound up in former enemy territory, but my Israeli and other Jewish friends had done the unthinkable: they’d moved to the land that had nearly extinguished them, learned to speak in the harsh consonants of the dreaded language, and betrayed their family and its unspeakable sufferings, or so their parents claimed. We were drawn to the stark reality of a walled-in, heavily guarded political enclave, long before the reunited German capital became an international magnet for start-ups and so-called creatives. We were the generation that had to justify itself for being here. It was hard not to be haunted by the city’s past, not to wonder how much of the human insanity that had taken place here was somehow imbedded in the soil—or if place is a thing entirely indifferent to us, the Earth entirely indifferent to the blood spilled on its battlegrounds.

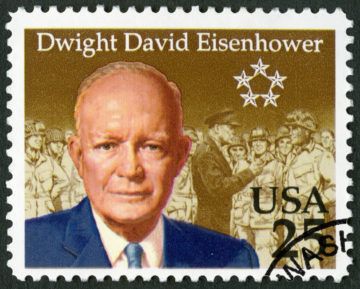

A Republican used to be someone like Dwight Eisenhower, a moderate who worked well with the opposing party, even meeting weekly with their leadership in the Senate and House. Eisenhower expanded social security benefits and, against the more right-wing elements of his party, appointed Earl Warren to be the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Warren, you’ll remember, wrote the majority opinion of Brown v Board of Education, Miranda v Arizona, and Loving v Virginia. If Dwight Eisenhower were alive today, he would be branded a RINO and a communist by his own party. I suspect he would become registered as unaffiliated.

A Republican used to be someone like Dwight Eisenhower, a moderate who worked well with the opposing party, even meeting weekly with their leadership in the Senate and House. Eisenhower expanded social security benefits and, against the more right-wing elements of his party, appointed Earl Warren to be the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Warren, you’ll remember, wrote the majority opinion of Brown v Board of Education, Miranda v Arizona, and Loving v Virginia. If Dwight Eisenhower were alive today, he would be branded a RINO and a communist by his own party. I suspect he would become registered as unaffiliated.

It’s not about dying, really—it’s about knowing you’re about to die. Not in the abstract way that we haphazardly confront our own mortality as we reach middle age and contemplate getting old. And not even in the way (I imagine) that someone with a terminal diagnosis might think about death—sooner than expected and no longer theoretical. It’s much more immediate than that.

It’s not about dying, really—it’s about knowing you’re about to die. Not in the abstract way that we haphazardly confront our own mortality as we reach middle age and contemplate getting old. And not even in the way (I imagine) that someone with a terminal diagnosis might think about death—sooner than expected and no longer theoretical. It’s much more immediate than that.