by Charlie Huenemann

“Monotonizing existence, so that it won’t be monotonous. Making daily life anodyne, so that the littlest thing will amuse.” —Bernardo Soares (Fernando Pessoa), The Book of Disquiet, translated by Richard Zenith, section 171

Senhor Soares goes on to explain that in his job as assistant bookkeeper in the city of Lisbon, when he finds himself “between two ledger entries,” he has visions of escaping, visiting the grand promenades of impossible parks, meeting resplendent kings, and traveling over non-existent landscapes. He doesn’t mind his monotonous job, so long as he has the occasional moment to indulge in his daydreams. And the value for him in these daydreams is that they are not real. If they were real, they would not belong to him. They would belong to others as public resources, and not reside in his own private realm. And what is more, if they were real, then what would he have left to dream? Far better, he thinks, “to have Vasques my boss than the kings of my dreams.” It’s more than that he doesn’t mind his monotonous job. On the contrary: the more monotonous his existence, the better his dreams.

Senhor Soares goes on to explain that in his job as assistant bookkeeper in the city of Lisbon, when he finds himself “between two ledger entries,” he has visions of escaping, visiting the grand promenades of impossible parks, meeting resplendent kings, and traveling over non-existent landscapes. He doesn’t mind his monotonous job, so long as he has the occasional moment to indulge in his daydreams. And the value for him in these daydreams is that they are not real. If they were real, they would not belong to him. They would belong to others as public resources, and not reside in his own private realm. And what is more, if they were real, then what would he have left to dream? Far better, he thinks, “to have Vasques my boss than the kings of my dreams.” It’s more than that he doesn’t mind his monotonous job. On the contrary: the more monotonous his existence, the better his dreams.

This is, of course, mere escapism from the crappy life he’s stuck with. His attempt to justify his monotonous existence by saying that it allows for better daydreams is as see-through as an 8-dollar verification program. He’s just coating his own unremarkable existence in cheap veneer. Soares, one might judge, should have the courage to make his life really better, to find something worth doing, worth taking pride in, and something of some value to others. He should dare to live dangerously. Maybe he could start a book club. There’s nothing wrong with daydreams, okay, but they should serve only as an occasion for a busy person to “recharge” and then return with greater focus to an active, productive life.

But as one gets older and realizes that most of life’s good stuff is contained between two ledger entries, one sees that if it weren’t for dreams, for stories and for art, for inventing personas and writing books through their hands and eyes, life would be insufferable. This is because our brains are too big. We are overpowered for the tasks modern life assigns us, and if we narrowed our focus to just what’s actually before us, we would find ourselves on the road with Estragon and Vladimir, surveying a bleak Beckettian stage, haunted by a vague sense that wasn’t there supposed to be something more, someone showing up who would make a difference? Read more »

There was a period in my life when I believed that all humans came from one man. This included his wife Eve. After that followed a period when I believed nothing and I thought that was enough.

There was a period in my life when I believed that all humans came from one man. This included his wife Eve. After that followed a period when I believed nothing and I thought that was enough. Does philosophy have anything to tell us about problems we face in everyday life? Many ancient philosophers thought so. To them, philosophy was not merely an academic discipline but a way of life that provided distinctive reasons and motivations for living well. Some contemporary philosophers have been inspired by these ancient sources giving new life to this question about philosophy’s practical import.

Does philosophy have anything to tell us about problems we face in everyday life? Many ancient philosophers thought so. To them, philosophy was not merely an academic discipline but a way of life that provided distinctive reasons and motivations for living well. Some contemporary philosophers have been inspired by these ancient sources giving new life to this question about philosophy’s practical import. Wendy Red Star. Winter – The Four Seasons Series, 2006.

Wendy Red Star. Winter – The Four Seasons Series, 2006.

Soon after the pandemic commenced its

Soon after the pandemic commenced its  There was a time when Google replied with images of and information about a world-class jockey, an Englishman born the same year Mark Twain published

There was a time when Google replied with images of and information about a world-class jockey, an Englishman born the same year Mark Twain published  This year marks the 42nd anniversary of the American release of The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy. Douglas Adams’ “five-book trilogy,” of which Hitchhiker’s was the first installment, led readers through a melancholy universe in which bureaucracy is the ultimate source of evil and shallow, self-serving incompetents are the galaxy’s greatest villains. The best-selling series helped shape the worldview of Generation X, capturing the nihilistic cynicism of the Thatcher/Reagan 1980s.

This year marks the 42nd anniversary of the American release of The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy. Douglas Adams’ “five-book trilogy,” of which Hitchhiker’s was the first installment, led readers through a melancholy universe in which bureaucracy is the ultimate source of evil and shallow, self-serving incompetents are the galaxy’s greatest villains. The best-selling series helped shape the worldview of Generation X, capturing the nihilistic cynicism of the Thatcher/Reagan 1980s.

Senhor Soares goes on to explain that in his job as assistant bookkeeper in the city of Lisbon, when he finds himself “between two ledger entries,” he has visions of escaping, visiting the grand promenades of impossible parks, meeting resplendent kings, and traveling over non-existent landscapes. He doesn’t mind his monotonous job, so long as he has the occasional moment to indulge in his daydreams. And the value for him in these daydreams is that they are

Senhor Soares goes on to explain that in his job as assistant bookkeeper in the city of Lisbon, when he finds himself “between two ledger entries,” he has visions of escaping, visiting the grand promenades of impossible parks, meeting resplendent kings, and traveling over non-existent landscapes. He doesn’t mind his monotonous job, so long as he has the occasional moment to indulge in his daydreams. And the value for him in these daydreams is that they are

Sughra Raza. Chughtai In Shabnam’s Living Room, November, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Chughtai In Shabnam’s Living Room, November, 2022.

I moved to Berlin in 1984, but have rarely written about my experiences living in a foreign country; now that I think about it, it occurs to me that I lived here as though in exile those first few years, or rather as though I’d been banished, as though it hadn’t been my own free will to leave New York. It’s difficult to speak of the time before the Wall fell without falling into cliché—difficult to talk about the perception non-Germans had of the city, for decades, because in spite of the fascination Berlin inspired, it was steeped in the memory of industrialized murder and lingering fear and provoked a loathing that was, for some, quite visceral. Most of my earliest friends were foreigners, like myself; our fathers had served in World War II and were uncomfortable that their children had wound up in former enemy territory, but my Israeli and other Jewish friends had done the unthinkable: they’d moved to the land that had nearly extinguished them, learned to speak in the harsh consonants of the dreaded language, and betrayed their family and its unspeakable sufferings, or so their parents claimed. We were drawn to the stark reality of a walled-in, heavily guarded political enclave, long before the reunited German capital became an international magnet for start-ups and so-called creatives. We were the generation that had to justify itself for being here. It was hard not to be haunted by the city’s past, not to wonder how much of the human insanity that had taken place here was somehow imbedded in the soil—or if place is a thing entirely indifferent to us, the Earth entirely indifferent to the blood spilled on its battlegrounds.

I moved to Berlin in 1984, but have rarely written about my experiences living in a foreign country; now that I think about it, it occurs to me that I lived here as though in exile those first few years, or rather as though I’d been banished, as though it hadn’t been my own free will to leave New York. It’s difficult to speak of the time before the Wall fell without falling into cliché—difficult to talk about the perception non-Germans had of the city, for decades, because in spite of the fascination Berlin inspired, it was steeped in the memory of industrialized murder and lingering fear and provoked a loathing that was, for some, quite visceral. Most of my earliest friends were foreigners, like myself; our fathers had served in World War II and were uncomfortable that their children had wound up in former enemy territory, but my Israeli and other Jewish friends had done the unthinkable: they’d moved to the land that had nearly extinguished them, learned to speak in the harsh consonants of the dreaded language, and betrayed their family and its unspeakable sufferings, or so their parents claimed. We were drawn to the stark reality of a walled-in, heavily guarded political enclave, long before the reunited German capital became an international magnet for start-ups and so-called creatives. We were the generation that had to justify itself for being here. It was hard not to be haunted by the city’s past, not to wonder how much of the human insanity that had taken place here was somehow imbedded in the soil—or if place is a thing entirely indifferent to us, the Earth entirely indifferent to the blood spilled on its battlegrounds.

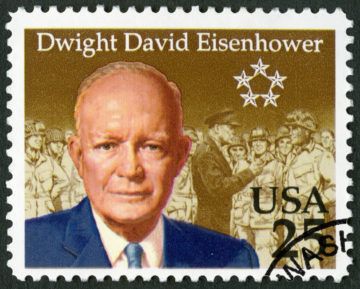

A Republican used to be someone like Dwight Eisenhower, a moderate who worked well with the opposing party, even meeting weekly with their leadership in the Senate and House. Eisenhower expanded social security benefits and, against the more right-wing elements of his party, appointed Earl Warren to be the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Warren, you’ll remember, wrote the majority opinion of Brown v Board of Education, Miranda v Arizona, and Loving v Virginia. If Dwight Eisenhower were alive today, he would be branded a RINO and a communist by his own party. I suspect he would become registered as unaffiliated.

A Republican used to be someone like Dwight Eisenhower, a moderate who worked well with the opposing party, even meeting weekly with their leadership in the Senate and House. Eisenhower expanded social security benefits and, against the more right-wing elements of his party, appointed Earl Warren to be the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Warren, you’ll remember, wrote the majority opinion of Brown v Board of Education, Miranda v Arizona, and Loving v Virginia. If Dwight Eisenhower were alive today, he would be branded a RINO and a communist by his own party. I suspect he would become registered as unaffiliated.