by Rafaël Newman

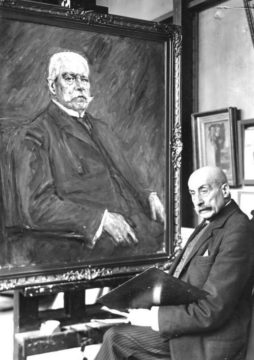

It’s been 90 years since Hitler was appointed German Chancellor, on January 30, 1933, despite his party, the NSDAP, having failed to achieve a majority in the elections to the Reichstag held the previous year; so naturally I’ve been thinking about Max Liebermann.

Born decades before the establishment of the German Empire, or Second Reich, in 1871, the painter Max Liebermann (July 20, 1847—February 8, 1935) was to die just as the Third Reich was rising to its hideous feet. Liebermann was a pillar of the German art world—or rather, he had become one by 1933, when he resigned from the Prussian Academy of Arts, the body he had served as president, but which had now fallen into line with the Nazis and had ceased exhibiting works by Jewish artists.

Max Liebermann was himself Jewish, but by the time of his death at the age of 87 he had long been accepted in the wider German bourgeois society into which he had been born, and which had persisted in its Prussian, Wilhelmine, and Weimar variations. After a rocky start to his career with scandalously “ugly” scenes of working-class life and “blasphemous” depictions of religious motifs, Liebermann would go on to play a leading role in the Berlin Secession, the fin-de-siècle movement opposed to the strictures of academic painting, which championed Impressionism and Realism and counted among its members such notable artists as Max Beckmann, Lovis Corinth, Käthe Kollwitz, and Otto Modersohn. Liebermann resisted the Secession’s eventual support for Expressionism, however, which moved him towards the conservative camp and prepared his entry into the Academy, the establishment’s artistic watchdog, and the mainstream of German culture. Read more »

I’m scared of birds. They’re dinosaurs, you know. They descend from the Jurassic when, just like in Jesus Loves Me, ‘they were big and we were small.’ Did you see those huge

I’m scared of birds. They’re dinosaurs, you know. They descend from the Jurassic when, just like in Jesus Loves Me, ‘they were big and we were small.’ Did you see those huge  Lots of people discredit the Myers-Briggs as just a horoscope, but it’s

Lots of people discredit the Myers-Briggs as just a horoscope, but it’s

Sughra Raza. Early Winter Shapes, January 2022.

Sughra Raza. Early Winter Shapes, January 2022. If we are to believe the most prominent of the writers we now lump under the category of “existentialism,” human suffering in the modern world is rooted in nihilism. But I wonder whether this is the best lens through which to view human suffering.

If we are to believe the most prominent of the writers we now lump under the category of “existentialism,” human suffering in the modern world is rooted in nihilism. But I wonder whether this is the best lens through which to view human suffering.

Blanchett’s performance has been much praised, and it is indeed a tremendous thing: she must be near the head of the queue for an Oscar this year. It’s a great performance in a genuinely worthwhile and absorbing film. I don’t think it really expands our understanding of the themes it features: power and the exploitation young hopefuls by the (seemingly) all powerful star, the question of great art and flawed artists and so on, but it’s possible to come out of the movie thinking that it has. Blanchett’s performance has a lot to do with that. So a great performance in a very good rather than great film (assuming such categories can really be employed so neatly).

Blanchett’s performance has been much praised, and it is indeed a tremendous thing: she must be near the head of the queue for an Oscar this year. It’s a great performance in a genuinely worthwhile and absorbing film. I don’t think it really expands our understanding of the themes it features: power and the exploitation young hopefuls by the (seemingly) all powerful star, the question of great art and flawed artists and so on, but it’s possible to come out of the movie thinking that it has. Blanchett’s performance has a lot to do with that. So a great performance in a very good rather than great film (assuming such categories can really be employed so neatly).

In

In  For the last several years, elected Republicans, full of anti-trans zeal, have challenged their opponents to define the word “woman.” They aren’t really curious. They’re setting a rhetorical trap. They’re taking a word that seems to have a simple meaning, because the majority of people who identify as women resemble each other in some ways, then refusing to consider any of the people who don’t.

For the last several years, elected Republicans, full of anti-trans zeal, have challenged their opponents to define the word “woman.” They aren’t really curious. They’re setting a rhetorical trap. They’re taking a word that seems to have a simple meaning, because the majority of people who identify as women resemble each other in some ways, then refusing to consider any of the people who don’t.

Let’s get the humble-bragging out of the way first: I’ve always had a remarkable memory.

Let’s get the humble-bragging out of the way first: I’ve always had a remarkable memory.