by Claire Chambers

Having begun Hindi and eventually reaching an intermediate level, I sailed into the vast ocean of the Urdu language. There, a novice again, I felt lost amid roiling currents. Yet I kept my compass pointed towards receptivity, hoping the winds of curiosity would steer me to the shores of understanding. I’m not there yet, so join me in my voyage.

Having begun Hindi and eventually reaching an intermediate level, I sailed into the vast ocean of the Urdu language. There, a novice again, I felt lost amid roiling currents. Yet I kept my compass pointed towards receptivity, hoping the winds of curiosity would steer me to the shores of understanding. I’m not there yet, so join me in my voyage.

As Liz Chatterjee wryly notes, ‘It is obligatory to point out that Urdu is a cognate of “horde” and its name came from the Muslim occupiers’ ordu, camp’. This is because the language developed among the armies of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal Empire, whose soldiers used a mixture of Indian languages and Persian as a lingua franca. Over time, this melange of languages came to be known as Urdu, and the Perso-Arabic script was used to write it.

Leaping forward a century or two, the Partition of 1947 was a traumatic event that left many Urdu-speaking people feeling alienated and excluded from the new Indian society. Partition has caused a shift in the perception of Urdu, which has been reduced to a language spoken primarily by the elderly and by Muslim minorities in India. After Partition, Urdu became the national language of Pakistan, while Hindi was India’s official language (soon joined by English). Despite this, Urdu continued to be spoken by millions of people in India, and it is still one of the 22 scheduled languages of India. In the decades following Partition, however, the use of Urdu in India declined due to a variety of political, social, and economic factors. Many people who spoke Urdu as their first language began to switch to Hindi, and the use of Urdu in education, films, and government business also languished. Today, Urdu remains an important language in India, but it is not as widely spoken as it once was. Read more »

On the night of July 13, 1977, the old god Zeus roused from his slumber with a scratchy throat. Reaching drowsily for the glass by his bedside, his arm knocked a handful of thunderbolts from the nightstand. Swift and white, they rattled across the floor to the mountain’s, his home’s, precipitous edge: off they rolled and dropped to plummet through the dark. That night, great projectiles of angular light splashed against and extinguished New York City’s billion fluorescent eyes.

On the night of July 13, 1977, the old god Zeus roused from his slumber with a scratchy throat. Reaching drowsily for the glass by his bedside, his arm knocked a handful of thunderbolts from the nightstand. Swift and white, they rattled across the floor to the mountain’s, his home’s, precipitous edge: off they rolled and dropped to plummet through the dark. That night, great projectiles of angular light splashed against and extinguished New York City’s billion fluorescent eyes.

When we speak about identity, we usually have in mind the various social categories we occupy—gender categories, nationality, or racial categories being the most prominent. But none of these general characteristics really define us as individuals. Each of us falls into various categories but so does everyone else. To say I’m a straight white male puts me in a bucket with millions of others. To add my nationality and profession only narrows it down a bit.

When we speak about identity, we usually have in mind the various social categories we occupy—gender categories, nationality, or racial categories being the most prominent. But none of these general characteristics really define us as individuals. Each of us falls into various categories but so does everyone else. To say I’m a straight white male puts me in a bucket with millions of others. To add my nationality and profession only narrows it down a bit.

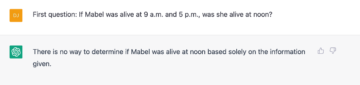

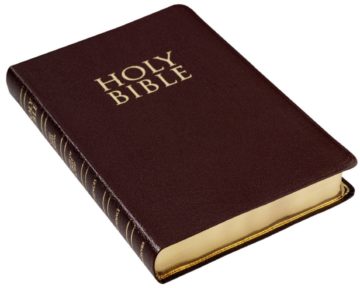

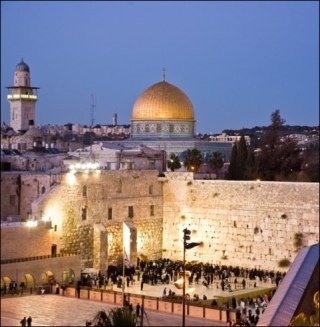

There are two possible attitudes towards Scripture. One is to regard it as the direct and infallible word of God. This leads to certain problems. The other one, equally compatible with devotion, is to regard it as the recorded writings of men (it almost always is men), however inspired, writing at a specific time and place and constrained by the knowledge and concerns of that time. This invites deeper study of what was at stake for the writers, the unravelling of different narrative strands and voices, and discussion of whatever message the Scriptures may have for our own times. I expect that most readers here will adopt the second approach, while those who adopt the first are not to be dissuaded by mere rational argument, so why am I even discussing it?

There are two possible attitudes towards Scripture. One is to regard it as the direct and infallible word of God. This leads to certain problems. The other one, equally compatible with devotion, is to regard it as the recorded writings of men (it almost always is men), however inspired, writing at a specific time and place and constrained by the knowledge and concerns of that time. This invites deeper study of what was at stake for the writers, the unravelling of different narrative strands and voices, and discussion of whatever message the Scriptures may have for our own times. I expect that most readers here will adopt the second approach, while those who adopt the first are not to be dissuaded by mere rational argument, so why am I even discussing it?

About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears.

About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears.

My father, the son of Italian immigrants, was a member of the working class. There were things within reach, and things that were not in reach, and he accepted this. He never pushed his children to broaden their horizons, and would have been satisfied to see them in traditional working-class vocations. When I came home from school eager to show off my grades, he poked fun at me. The prospect of pursuing an intellectual career was alien to him; in his view, taking out student loans to go to college or university was a way for banks to trap the “little guy.” When I presented him with the papers, he refused to sign. There was no discussion. I eventually moved out and managed to get my BFA anyway, and when I wound up as a finalist for a Fulbright, the doctor who performed the general checkup required by the awarding commission—I was still covered by my father’s Blue Cross plan, but only because I was still technically a dependent and it didn’t cost him anything—took him aside and told him that a Fulbright would be “quite a feather in your daughter’s cap.”

My father, the son of Italian immigrants, was a member of the working class. There were things within reach, and things that were not in reach, and he accepted this. He never pushed his children to broaden their horizons, and would have been satisfied to see them in traditional working-class vocations. When I came home from school eager to show off my grades, he poked fun at me. The prospect of pursuing an intellectual career was alien to him; in his view, taking out student loans to go to college or university was a way for banks to trap the “little guy.” When I presented him with the papers, he refused to sign. There was no discussion. I eventually moved out and managed to get my BFA anyway, and when I wound up as a finalist for a Fulbright, the doctor who performed the general checkup required by the awarding commission—I was still covered by my father’s Blue Cross plan, but only because I was still technically a dependent and it didn’t cost him anything—took him aside and told him that a Fulbright would be “quite a feather in your daughter’s cap.”

Sughra Raza. Just a Street Corner. Boston, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Just a Street Corner. Boston, 2022.