by Mike Bendzela

Narrative is the elucidation of backstory. Thus, narrative partakes of other stories, is composed of them. There is no infinite regress of narratives, though. At the end lies a cosmology, which I use here to mean a master story, or, “a doctrine describing the natural order of the universe.” This the ground of all narrative. Our stories must in some way enact a cosmology.

Until recently, cosmologies have not been based on empirical observation and evidence—because they couldn’t be. What did we know? How could we even know that we didn’t know? Instead, we relied on revelation and tradition. Such narratives deprived of a factual backstory may speculate about the causes of action, but such stories would be shams. When our backstory is wrong, our story is absurd, but we have had no way of knowing this—until now.

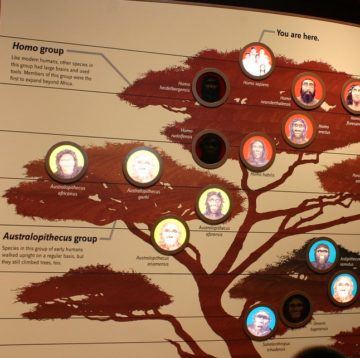

The evolutionary history of our species negates and overturns all previous cosmologies. Ever since Darwin, it seems most fiction writers have pretended not to notice and continue to cater to false backstories. But I could be wrong: I don’t read much new fiction anymore.

The cosmological backstory, updated, is this: We are all animals. We are one family. But we are exquisitely paradoxical: “We’re the same, but different!” Despite our unitary history, natural selection “designed” us to be hypersensitive to trivial variations amongst ourselves. We make these distinctions—between an “us” and a “them”—to project our animal natures onto others, to dehumanize and thus exterminate them, for our own benefit. We usually regard this as a sacred impulse. It is the ultimate cause of all discord.

Licking Our Evolutionary Destiny

With our culture we have managed to loosen the noose of natural selection. We have sanitation, agriculture, surgeries, vaccines, antibiotics, and technologies that co-opt, preempt, and negate the culling effects of natural selection. And yet our adaptive behaviors still cling to us. Some of these behaviors are decidedly maladaptive in the modern world. Like a hankering after fatty, sweet comestibles while surrounded by strip mall food courts.

To say a behavior is adaptive is not to say it is “good” or “bad”. “Adaptive” is merely a descriptor. Adaptive is as adaptive does.

Is it “good” that baby koalas (“joeys”) lick their mothers’ anuses? It is surely adaptive. By licking their mothers’ anuses, joeys ingest a load of symbionts necessary for the digestion of otherwise indigestible eucalyptus leaves. If you could ask the animals themselves, they would say, “Of course it’s good!” But imagine a world where these animals had created a culture in which said symbionts were available in new, fortified foodstuffs, capsules, soft drinks, injections and treats.

The joeys would go right on licking their mothers’ anuses, much to their mothers’ annoyance and keeping them from their affairs.

And if a program were devised to ban anus-licking behavior and wean those babies immediately, mayhem would ensue.

Who are we to think we are any different?

The analogy in the human animal to the anus-licking behavior in koalas: Identity politics (surely a redundant term, like “dark black”); fissioning, foment, extermination.

There was a time when these were adaptive behaviors. Not “good.” Not preferable. Just adaptive. One group of apes got to ravage another group while keeping their piety intact. They deserved to commandeer and monopolize resources. Backstory said so: “Thou art my people!” (Isaiah 51:16) The paradox: there are those who did not specially want it to happen.

10 So the assembly sent twelve thousand fighting men with instructions to go to Jabesh Gilead and put to the sword those living there, including the women and children. 11 “This is what you are to do,” they said. “Kill every male and every woman who is not a virgin.” 12 They found among the people living in Jabesh Gilead four hundred young women who had never slept with a man, and they took them to the camp at Shiloh in Canaan. (Judges 21.)

Why would evolution permit us such damaging views of the world? Why evolve cosmologies that are deceptive, that are blind to the evolutionary processes through which they have arisen?

Because natural selection itself is blind. To persist, a cosmology doesn’t have to be true, it just has to inspire enough savagery to propagate itself. It has to anoint “us” with piety at the expense of “them”. Be like us, or die.

Paradoxically–and mercifully–natural selection has endowed us with language-based culture . . . hence, storytelling . . . which has allowed us to counter the effects of natural selection.

But on to some threadbare, obsolete backstories.

Oedipus, Schmoedipus

Older works under extinct cosmologies stand out as wonders now—artefacts, curiosities, grotesques. The ancient Greek world view that forms the background to Oedipus Rex is certainly dead and gone. The Greeks believed in oracles and auguries that said our actions are determined by gods that are incensed over the infractions of our parents. But the traditional view of Oedipus’s father Laius’s infraction (an indiscretion of hospitality, homosexual rape) doesn’t even figure into Sophocles’ narrative.

JOCASTA: There was an oracle once that came to Laius,

[…] and it told him

that it was fate that he should die a victim

at the hands of his own son, a son to be born

of Laius and me.

Still, the gods do with Oedipus as they wish, for the sake of Laius. They squash poor Oedipus like vermin. No amount of mayhem makes these gods blush. And Jocasta never asks, “Why?”

The result is that Oedipus’s story sounds right out of a comic book. One experiences neither sympathy nor identification, just moral horror compounded with hilarity. No realism here, with a plot dependent on such oracles. The gods are indiscriminate and unfair in their punitive plotting, period.

I believe the Greek myth-makers desperately sought to account in some way for universal havoc and suffering. Let it be anything but meaningless, random chance! As if channeling Ecclesiastes, Jocasta intuits,

Why should man fear since chance is all in all

for him, and he can clearly foreknow nothing?

Best to live lightly, as one can, unthinkingly.

Better Thebes become a prison and leper colony than succumb to such atheism!

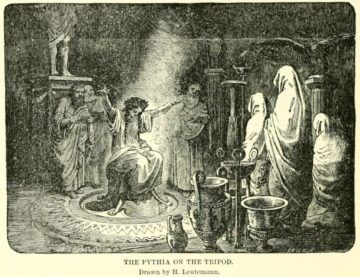

For deliverance, the Thebans appeal to the very fount of their suffering—the cursed king, Oedipus. The bogus cosmology renders up a plot full of holes. Oedipus’s brother-in-law, Creon, goes to the oracle at Delphi to learn how to reverse the curse:

King Phoebus [Apollo] in plain words commanded us

to drive out a pollution from our land. . . .

What “plain words”? Apollo never tells Creon the “pollution” is King Oedipus himself. Suddenly, the god is coy.

Oedipus curses any man who knows the murderer and fails to turn him in. Rather he should curse the god to his face! He knows this:

Would not one rightly judge and say that on me

these things were sent by some malignant God?

Apollo’s roundabout messenger is the seer Tiresias, who tells Oedipus what Apollo wouldn’t tell Creon:

[Y]ou are the land’s pollution.

But how is Oedipus supposed to know what Tiresias is talking about? The gods have put blinders on Oedipus, and then they beat him with a stick. As a result, we have that ridiculous scene wherein Oedipus and Jocasta virtually celebrate the death of his adoptive father, Polybus, because it “means” the oracles are bullshit. Hooray! Dad is dead, but I didn’t kill him! But in this cosmology such oracles must be true—they are of the gods!—so human suffering is the punchline of a cosmic joke.

These gods are so appalling that they even carefully word their oracles to allow themselves plausible deniability for the suffering they cause.

APOLLO: Don’t look at me. I told the dude he would kill the father that begot him, not his adoptive father. It ain’t my fault he couldn’t see the difference.

When the blinders finally come off at the end, Oedipus gouges his eyes out with his dead mother-wife’s brooch.

The moral: Your little self ain’t worth knowing, such knowledge is a curse, get over it. How odd that a whole modern school of psychoanalytic thought was based on this.

Lying In Those Improper Beds

The Greco-Roman cosmology—and its gods—eventually died out with the wholesale shift to a Judeo-Christian cosmology, all the Neo-Platonism and Neo-Classicism in Europe notwithstanding. But this new world is as intolerable a place as Oedipus’s Thebes.

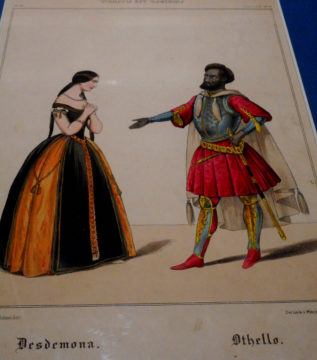

For example, in Shakespeare’s Othello, the Christian characters’ lives become ensnared in one psychopath’s satanic lies, and mayhem ensues.

In a rather odd scene towards the end, Desdemona lies smothered in her nuptial bed but not dead (?). She has yet more to say:

O, falsely, falsely murdered!

Emilia perks up and asks, “O, who hath done this deed?” (with the hulking, murderous Othello standing right there beside her). Then comes Desdemona’s famous perjury:

Nobody—I myself. Farewell.

Commend me to my fine lord [husband]. O, farewell!

[She dies.]

We’re left to make sense of this weird deathbed fib through a Christian cosmology, one that calls for self-effacement on behalf of the Next World.

“You heard her say herself, it was not I,” Othello prompts Emilia; then, just as suddenly:

She’s like a liar gone to burning hell!

Which, in this cosmology, is strictly true: False witness on one’s deathbed? Damnation!

Why does she lie? Is it so she can be reunited with her stupid, beloved husband in the afterlife—in Hell? (“O fool, fool, fool!” he says of himself). The thought is touchingly ridiculous, and ridiculously touching (Desdemona and Othello embracing in Hell: I could cry just thinking about it). The emotional tenor of Othello makes it my favorite Shakespeare play, even though the superstitious assumptions put me off. At least there aren’t any ghosts as in the other plays.

That’s one hell of a drag on Earthly existence, thinking that eternal damnation dogs your every step. Almost as bad as Apollo’s curse.

So what, then, would be a Darwinian reading of this narrative? It does not compute. One cannot embark on such an interpretation of the story, as it was not composed with an evolutionary view of the world but within a religious tradition antithetical to the Darwinian perspective.

It’s clear that in Othello we have a retelling of the Legend of the Fall. Othello and Desdemona’s marriage is depicted as Edenic, if entered into rashly. “The Fair Desdemona” so clearly represents the original prelapsarian innocence of humanity that she’s not a very believable character. Othello is a mixed bag, a crafty war General with naïve ideas about love and trust. Iago is cast as the satanic serpent in the garden, whose “motiveless malignity” (a phrase that goes back to the poet Coleridge) destroys the citadel of their marriage with lies.

(Never mind that in the original Hebrew tradition of Genesis, the serpent, nahash, is not Satan. The serpent doesn’t even lie!

“You will not certainly die,” the serpent said to the woman. “For God knows that when you eat from [the Tree of Knowledge] your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.”

This is all strictly true: Their eyes are opened, and they are not killed; they are forbidden from eating of the Tree of Life because they are mortal to begin with!)

The serpent, Iago, poisons the General’s mind with the lie that his Lieutenant, Cassio, is boning his wife behind his back; Othello blindly accepts the lie as readily as numb-nuts Adam accepts the fruit from Eve; so, he smothers his fair, innocent wife in their nuptial bed, and then all hell breaks loose. “The wages of sin is death.” Discovering he has been hoodwinked–embarrassed, disgraced, bereft–Othello stabs himself and falls onto his dead wife in bed. Lodovico, Desdemona’s cousin, has the final word for the satanic Iago before he is led off to be tortured:

Look on the tragic loading of this bed;

This is thy work . . .

Satan has tempted the humans and ruined creation. Beautiful, tragic, but ultimately doctrinal. Iago embodies the problem of theodicy: Why the hell would a loving God plant a hand grenade in His perfect creation? Even when Othello asks him WTF? directly before he kills himself, Iago basically answers, “Don’t ask.”

Demand me nothing. What you know, you know.

From this time forth I never will speak word.

Primordial Fiction, Anyone?

So what do we do now that the old cosmologies are dead and rotten? We can’t really interpret the old stories in terms of a world view the traditional writers were clueless about. It’s back to the drawing board.

It’s long past time we asked for narratives that elucidate our evolutionary heritage and its consequences. One aspect of such a world is that conflict amongst competing factions is as inevitable as flakes amongst stone tool makers. To remake our literary tradition in light of the Darwinian view, we must start somewhere, anywhere, as there is, strictly speaking, no conspicuous beginning; so, simply, during some once upon a time ago. We could begin with the animal Fable, one of our oldest literary forms, into which we may import Darwinian content:

Once their tunnels had become stocked with earthworms, the moles (Scalopus aquaticus) could rest and contemplate their good fortune.

“The world is obviously designed with our interests in mind,” they said, “as this stock of worms testifies.”

Their contentment was disrupted when black rat snakes (Pantherophis obsoletus) discovered the moles’ tunnels. The snakes feasted on the moles, multiplied, and spread to other tunnels. Thus, the mole’s quaint view of the world was extinguished.

“The world is here for our taking,” the snakes concluded. “We’ve been blessed with this cornucopia.”

As the snakes increased, they caught the eye of red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis) perched high in the trees. The snakes began to suffer from raptor attacks, even as the moles went into decline from their feeding. The snakes’ reign was ended.

“Who else sees the world as completely as we do?” the hawks observed. “We have been so positioned to take advantage of all that we can behold.”

The hawks’ preeminence was short-lived: hominins and their arrows made sure of that.

Moral: Conceit is a natural habit of mind.

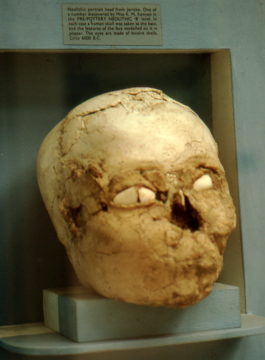

Our evolutionary history—our cosmology—includes the immense mass grave that follows in the wake of natural selection. This is a our backstory. We march forth out of this morass, telling our pious lies. Stories must expose the liars for who they are, un-bury and bring to light their victims’ bodies, for the sake of culture and learning, our sole remedy for the horrors of natural selection. Let the work begin.

_____________________________

Images

“Human Family Tree” by Ryan Somma is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

“Momma and Baby Koala 3” by alan.stoddard is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0.

Oracle at Delphi by History Maps. Public Domain.

“‘Otello’ by Gioachino Rossini – Lithography by Schneider, Berlin – Exhibition ‘Rossini. Neapolitan fury: 1868-2018’ at ‘MeMus’=Memory and Music” by Carlo Raso is marked with Public Domain Mark 1.0.

“Neolithic portrait head from Jericho” by gbaku is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.