by Dwight Furrow

If a rectangular canvas splashed with paint and lines can express freedom or joy, why not liquid poetry?

If a rectangular canvas splashed with paint and lines can express freedom or joy, why not liquid poetry?

Works of art are pleasing but they are also intended to communicate or express something. Something is shown or made manifest through a work of art. In many cases what is communicated is some feeling or attitude that in some way belongs to the artist. But not all art is about self-expression. Some works are intended to reveal something about the artist’s materials when worked on in a particular way. For instance, many Impressionist works by Monet and others expressed a singular relationship between color and light, although these works also communicate something about the artist’s point of view regarding what is being expressed. Some works reveal something about their subject matter when placed in an assemblage with other subject matters regardless of whether they reflect anything about the artist. A landscape may express the relationship between a building and an atmosphere, without expressing something important about the artist’s psychology or biography. To express is to reveal something hidden or not obvious but that need not be restricted to human psychology. Works of art invite us to feel something about them but that feeling need not be something possessed by the artist. Hamlet expresses uncertainty and ambivalence independently of any feelings Shakespeare may have had and there is no need to investigate Shakespeare’s biography to grasp what Hamlet is expressing.

Even when art is expressing some human quality, the expression reaches far beyond facts about an individual artist. The 19th Century German philosopher Hegel argued that art expresses a shared sense of “the deepest interests of mankind, the most comprehensive truths of the spirit”. Art’s role for Hegel is to express something whole cultures can share when brought to light and put on a pedestal.

What about wine? Can wine be expressive in the way works of art are expressive? I’ve argued that wine can express emotion, although only occasionally is that related to a winemaker’s feelings. But here I want to focus on other dimensions of wine’s expressiveness that go beyond the expression of an individual’s emotions or attitudes. Read more »

In giving an account of the aesthetic value of wine, the most important factor to keep in mind is that wine is an everyday affair. It is consumed by people in the course of their daily lives, and wine’s peculiar value and allure is that it infuses everyday life with an aura of mystery and consummate beauty. Wine is a “useless” passion that has a mysterious ability to gather people and create community. It serves no other purpose than to command us to slow down, take time, focus on the moment, and recognize that some things in life have intrinsic value. But it does so in situ where we live and play. Wine transforms the commonplace, providing a glimpse of the sacred in the profane. Wine’s appeal must be understood within that frame.

In giving an account of the aesthetic value of wine, the most important factor to keep in mind is that wine is an everyday affair. It is consumed by people in the course of their daily lives, and wine’s peculiar value and allure is that it infuses everyday life with an aura of mystery and consummate beauty. Wine is a “useless” passion that has a mysterious ability to gather people and create community. It serves no other purpose than to command us to slow down, take time, focus on the moment, and recognize that some things in life have intrinsic value. But it does so in situ where we live and play. Wine transforms the commonplace, providing a glimpse of the sacred in the profane. Wine’s appeal must be understood within that frame. The Doomsday Scenario, also known as the Copernican Principle, refers to a framework for thinking about the death of humanity. One can read all about it in a recent

The Doomsday Scenario, also known as the Copernican Principle, refers to a framework for thinking about the death of humanity. One can read all about it in a recent  Philosophers have spilled a great deal of ink attempting to nail down once and for all the necessary and sufficient conditions for a thing’s being a work of art. Many theories have been proposed, which can seem in retrospect to have been motivated by particular works or movements in the history of art: if you’re into Cézanne, you might think art is “significant form,” but if you’re impressed by Andy Warhol, you might that arthood is not inherent in a work’s perceptible attributes, but is instead something conferred upon it by members of the artworld.

Philosophers have spilled a great deal of ink attempting to nail down once and for all the necessary and sufficient conditions for a thing’s being a work of art. Many theories have been proposed, which can seem in retrospect to have been motivated by particular works or movements in the history of art: if you’re into Cézanne, you might think art is “significant form,” but if you’re impressed by Andy Warhol, you might that arthood is not inherent in a work’s perceptible attributes, but is instead something conferred upon it by members of the artworld.

It is fashionable to say that great wine is made in the vineyard. There is a lot of truth to that slogan but in fact wine is made by a complex assemblage with various factors influencing the final product. Last month

It is fashionable to say that great wine is made in the vineyard. There is a lot of truth to that slogan but in fact wine is made by a complex assemblage with various factors influencing the final product. Last month  In the Third Essay of On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche levels a powerful attack on the modern Platonistic conception of mind and nature, urging us to reject such “contradictory concepts” as “knowledge in itself,” or the idea of “an eye turned in no particular direction, in which the active and interpreting forces, through which alone seeing becomes seeing something, are supposed to be lacking.” More recently, Donald Davidson’s attack on the dualism of conceptual scheme and empirical content, and thus of belief and meaning, requires us to see inquiry into how things are as essentially interpretative.

In the Third Essay of On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche levels a powerful attack on the modern Platonistic conception of mind and nature, urging us to reject such “contradictory concepts” as “knowledge in itself,” or the idea of “an eye turned in no particular direction, in which the active and interpreting forces, through which alone seeing becomes seeing something, are supposed to be lacking.” More recently, Donald Davidson’s attack on the dualism of conceptual scheme and empirical content, and thus of belief and meaning, requires us to see inquiry into how things are as essentially interpretative. Discussions of the factors that go into wine production tend to circulate around two poles. In recent years, the focus has been on grapes and their growing conditions—weather, climate, and soil—as the main inputs to wine quality. The reigning ideology of artisanal wine production has winemakers copping to only a modest role as caretaker of the grapes, making sure they don’t do anything in the winery to screw up what nature has worked so hard to achieve. To a degree, this is a misleading ideology. After all, those healthy, vibrant grapes with distinctive flavors and aromas have to be grown. A “hands off” approach in the winey just transfers the action to the vineyard where care must be taken to preserve vineyard conditions, adjust to changes in weather, plant and prune effectively and strategically, adjust the canopy and trellising methods when necessary, watch for disease, and pick at the right time.

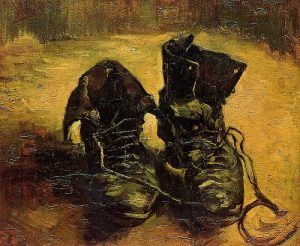

Discussions of the factors that go into wine production tend to circulate around two poles. In recent years, the focus has been on grapes and their growing conditions—weather, climate, and soil—as the main inputs to wine quality. The reigning ideology of artisanal wine production has winemakers copping to only a modest role as caretaker of the grapes, making sure they don’t do anything in the winery to screw up what nature has worked so hard to achieve. To a degree, this is a misleading ideology. After all, those healthy, vibrant grapes with distinctive flavors and aromas have to be grown. A “hands off” approach in the winey just transfers the action to the vineyard where care must be taken to preserve vineyard conditions, adjust to changes in weather, plant and prune effectively and strategically, adjust the canopy and trellising methods when necessary, watch for disease, and pick at the right time. Despite the continued influence of formalism in the 20th Century there were currents of dissent that took an opposing position. Thinkers as diverse as Heidegger, Whitehead and Deleuze were arguing that genuine aesthetic appreciation is not about form but the unraveling of form. Despite their considerable differences, each was arguing that the most important kinds of aesthetic experiences are those in which the dominant foreground and design elements of a work are haunted by a background of contrasting effects that provide depth. It’s the conflict between foreground and background, surface and depth, between what is known and what is mysterious that give art its allure. The uncanny is the key to art worthy of the name. For example, for Heidegger in his famous study of Van Gogh’s A Pair of Shoes, it’s the seemingly insignificant brushstrokes in the background of the painting that allow amorphous figures to emerge and begin to take to shape as we view it. The background figures preserve ambiguity and allow the concealing and unconcealing of multiple interpretations to take place, which Heidegger argues, are at the heart of a work of art.

Despite the continued influence of formalism in the 20th Century there were currents of dissent that took an opposing position. Thinkers as diverse as Heidegger, Whitehead and Deleuze were arguing that genuine aesthetic appreciation is not about form but the unraveling of form. Despite their considerable differences, each was arguing that the most important kinds of aesthetic experiences are those in which the dominant foreground and design elements of a work are haunted by a background of contrasting effects that provide depth. It’s the conflict between foreground and background, surface and depth, between what is known and what is mysterious that give art its allure. The uncanny is the key to art worthy of the name. For example, for Heidegger in his famous study of Van Gogh’s A Pair of Shoes, it’s the seemingly insignificant brushstrokes in the background of the painting that allow amorphous figures to emerge and begin to take to shape as we view it. The background figures preserve ambiguity and allow the concealing and unconcealing of multiple interpretations to take place, which Heidegger argues, are at the heart of a work of art.

Although frequently lampooned as over-the-top, there is a history of describing wines as if they expressed personality traits or emotions, despite the fact that wine is not a psychological agent and could not literally have these characteristics—wines are described as aggressive, sensual, fierce, languorous, angry, dignified, brooding, joyful, bombastic, tense or calm, etc. Is there a foundation to these descriptions or are they just arbitrary flights of fancy?

Although frequently lampooned as over-the-top, there is a history of describing wines as if they expressed personality traits or emotions, despite the fact that wine is not a psychological agent and could not literally have these characteristics—wines are described as aggressive, sensual, fierce, languorous, angry, dignified, brooding, joyful, bombastic, tense or calm, etc. Is there a foundation to these descriptions or are they just arbitrary flights of fancy?

That music and emotion are somehow linked is one of the more widely accepted assumptions shared by philosophical aesthetics as well as the general public. It is also one of the most persistent problems in aesthetics to show how music and emotion are related. Where precisely are these emotions that are allegedly an intrinsic part of the musical experience? Three general answers to this question are possible. Either the emotion is in the musician—the composer or performer—in which case the music is expressing that emotion. Or the emotion is in the music itself, in which case the music somehow embodies the emotion. Or the emotion is in the listener, in which case the music arouses the emotion.

That music and emotion are somehow linked is one of the more widely accepted assumptions shared by philosophical aesthetics as well as the general public. It is also one of the most persistent problems in aesthetics to show how music and emotion are related. Where precisely are these emotions that are allegedly an intrinsic part of the musical experience? Three general answers to this question are possible. Either the emotion is in the musician—the composer or performer—in which case the music is expressing that emotion. Or the emotion is in the music itself, in which case the music somehow embodies the emotion. Or the emotion is in the listener, in which case the music arouses the emotion. Beauty has long been understood as the highest form of aesthetic praise sharing space with goodness, truth, and justice as a source of ultimate value. But in recent decades, despite calls for its revival, beauty has been treated as the ugly stepchild banished by an art world seeking forms of expression that capture the seedier side of human existence. It is a sad state of affairs when the highest form of aesthetic praise is dragged through the mud. Might the problem be that beauty from the beginning has been misunderstood?

Beauty has long been understood as the highest form of aesthetic praise sharing space with goodness, truth, and justice as a source of ultimate value. But in recent decades, despite calls for its revival, beauty has been treated as the ugly stepchild banished by an art world seeking forms of expression that capture the seedier side of human existence. It is a sad state of affairs when the highest form of aesthetic praise is dragged through the mud. Might the problem be that beauty from the beginning has been misunderstood? One starting point for any philosophical account of language is that the truth of a statement depends both on what it means and on how the world is. Handily for contemporary pragmatists of my stripe, this fits neatly with the post-Davidsonian project of overcoming the dualism of conceptual scheme and empirical content. All we need to do is show that the two factors that make up truth are not so detachable as contemporary dualists claim.

One starting point for any philosophical account of language is that the truth of a statement depends both on what it means and on how the world is. Handily for contemporary pragmatists of my stripe, this fits neatly with the post-Davidsonian project of overcoming the dualism of conceptual scheme and empirical content. All we need to do is show that the two factors that make up truth are not so detachable as contemporary dualists claim.