by Dwight Furrow

Traditional aesthetics at least since Kant has been focused on the form of a work of art. It’s the design and composition of a work that strikes us beautiful. In a genuine aesthetic judgment, according to this view, we do not enjoy Van Gogh’s Starry Night because it contains our favorite color or reminds us of the night sky in our hometown. It’s the arrangement of colors and shapes that compels our pleasure and warrants the judgment of beauty. Even pre-Kantian, classical conceptions of aesthetics were focused on form in that they emphasized symmetry and harmony as criteria for beauty.

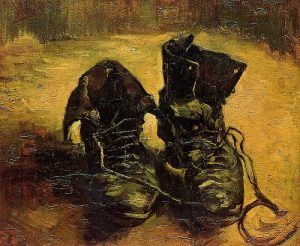

Despite the continued influence of formalism in the 20th Century there were currents of dissent that took an opposing position. Thinkers as diverse as Heidegger, Whitehead and Deleuze were arguing that genuine aesthetic appreciation is not about form but the unraveling of form. Despite their considerable differences, each was arguing that the most important kinds of aesthetic experiences are those in which the dominant foreground and design elements of a work are haunted by a background of contrasting effects that provide depth. It’s the conflict between foreground and background, surface and depth, between what is known and what is mysterious that give art its allure. The uncanny is the key to art worthy of the name. For example, for Heidegger in his famous study of Van Gogh’s A Pair of Shoes, it’s the seemingly insignificant brushstrokes in the background of the painting that allow amorphous figures to emerge and begin to take to shape as we view it. The background figures preserve ambiguity and allow the concealing and unconcealing of multiple interpretations to take place, which Heidegger argues, are at the heart of a work of art.

Despite the continued influence of formalism in the 20th Century there were currents of dissent that took an opposing position. Thinkers as diverse as Heidegger, Whitehead and Deleuze were arguing that genuine aesthetic appreciation is not about form but the unraveling of form. Despite their considerable differences, each was arguing that the most important kinds of aesthetic experiences are those in which the dominant foreground and design elements of a work are haunted by a background of contrasting effects that provide depth. It’s the conflict between foreground and background, surface and depth, between what is known and what is mysterious that give art its allure. The uncanny is the key to art worthy of the name. For example, for Heidegger in his famous study of Van Gogh’s A Pair of Shoes, it’s the seemingly insignificant brushstrokes in the background of the painting that allow amorphous figures to emerge and begin to take to shape as we view it. The background figures preserve ambiguity and allow the concealing and unconcealing of multiple interpretations to take place, which Heidegger argues, are at the heart of a work of art.

Great works of art contain disparity, contrast, and tension, an abundance of the unfamiliar and the extraordinary, ambiguously disclosed, that haunt the surface features of the work and that are never fully resolved. The work as it unfolds in our experience is in the process of striving to resolve the tension. But great stories never fully resolve tension. Great paintings usually have elements in the background that haunt and trouble the surface features. Great musical works have always made use of dissonance that create tension with the dominant harmonic structure. With regard to beauty the key that separates it from what is pleasing or pretty is the sense of mystery, created by this disunity at the core of the work, that draws us in.

So what does this have to do with wine?

Several dimensions of wine exhibit a similar relationship between foreground form and background depth. Great wines have dominant flavor and aroma notes that have clarity and focus and exhibit harmony in that they have a sense of cohesion, with each element working together in an overall pattern. But these dominant aromas stand out against a background of hints and nuances, aromas that can be only dimly perceived yet give the wine a sense of depth. Such wines are described as complex because they seem to have many dimensions that persist as a penumbra around the central aromas as our attention shifts back and forth from foreground to background. This is why tasting notes often contain a seemingly endless list of aroma descriptors which can baffle less practiced tasters. The aromas are often so faint they are open to multiple interpretations and are susceptible to perceptual threshold variations among tasters. Yet, even when they cannot be clearly discerned and identified, they contribute to the depth and richness of the wine, functioning much as a mirepoix does in a sauce. The carrots, celery and onion cannot be picked out as distinct flavor notes yet they add richness to the sauce.

These background aromas sometimes develop a character that is in tension with the foreground aromas. Especially as wines age, the dominant fruit, floral and herbal scents are surrounded by aromas that remind us of gravel, tar, barnyard, cat pee, petroleum, musk, sweaty saddle, smoke, gunflint, and bacon fat, not to mention the less prized aromas such as band aid, nail polish remover, and rotten egg. These are not pretty and introduce elements in the wine that are disruptive, deviant, and in themselves often ugly. If we think of wine as exhibiting flavor themes, these divergent aromas are clearly in tension with the dominant fruit and herbal themes. A pretty peach-and-apple-inflected Riesling from Germany’s Mosel region that begins to develop diesel fuel aromas in the bottle is acquiring tension and conflict that adds to the impression of depth. When sufficiently reticent so they don’t overwhelm the dominant fruit aromas, most professional wine tasters would argue such wines exhibit harmony. But there is an important aesthetic difference between a harmony of similar qualities vs. a harmony achieved through balanced tension with qualities that are from a different flavor world.

Beauty is at its highest intensity when there is contrast between the components that make up the experience, when the background elements are brought into animated tension with the foreground. As the early 20th Century American philosopher Alfred North Whitehead argued,

“Contrast elicits depth, and only shallow experience is possible when there is a lack of patterned contrast. (Adventures in Ideas, 268)

I doubt that “harmonious” is the best way to describe wines whose beauty depends on contrast. Great wines jettison harmony in favor of paradox and the sublime.

When we drink the wine, a different dimension of tension-generated depth emerges. We tend to think of the structure of a wine as something static and clearly discernible. Experienced tasters can analytically identify and judge the level of fruit concentration, body, alcohol, tannins, and acidity that make up a wine’s structure. But when we focus more closely on the experience of drinking, the wine is in fact in motion undergoing several changes in the mouth. It moves through phases as if animated by an invisible force.

Most wines exhibit their fruit quality first and we get an initial impression of the body of the wine. But as we swallow, we begin to feel the sharpness of the acidity along with a swelling sensation as if the wine is seeking a crescendo. Drying sensations caused by tannins in red wines (and other phenols in white wines) then begin to be sensed, as the wine seems to broaden and acquire a foundation initiating the finish, as the fruit fades and a long entangling dance between sharp acidity and drying tannins plays out. Thus, a wine might have a layer of lush, placid fruit while simultaneously revealing a sharply etched emerging layer of lifted floral and mineral notes that become more and more prominent, giving the wine a sense of gathering forces and upward movement. Meanwhile, drying tannins stimulate more and more areas of the mouth and throat yielding an impression of horizontal and descending motion that has its own pace and rhythm. The wine’s structure is literally making itself in the mouth as the various components seem to pull apart and come together setting up a rhythmic oscillation as our attention shifts among these complex movements. The softness of the fruit is set off by the growing intense acidity that pulls the wine in one direction while the broadening tannins pull it in different direction only to have the fruitiness return in a different guise as the finish develops. The speed at which these changes occur and the dynamic range they exhibit introduce tension and conflict which are only partly resolved in a moment of harmony where the wine’s counter-forces come together in a state of agitated equilibrium. The evanescent aroma and flavor notes gradually fade into a roiling, energetic sea that heightens the epiphany of depth.

Most quality wines share this general sequence of movements. But each wine has its own individual force signature (which I describe in more detail here). Although there is no strict correlation between price and quality, most inexpensive wines and some premium wines exhibit only a modest degree of movement or vitality on the palate. But many high quality wines are as dynamic as a Beethoven symphony, compelling our interest because of the intensity and complexity of their motion and the sense of vitality that emerges.

Although these movements are traceable with careful observation, they happen quickly and in the normal course of the tasting experience operate in the background and are thus part of the aesthetics of depth which I’ve been describing. The more we attend to these dimensions of complexity the more a wine seems to have an unlimited reservoir of unfathomable mystery that probes the ocean floor of the spirit, goading the imagination, a lure for feeling and thought, like any great work of art.

For more on the aesthetics of wine and food visit Edible Arts or consult American Foodie: Taste, Art and the Cultural Revolution.