by Dave Maier

Last time, in part 1, I distinguished two strategies for combating philosophical modernism of a certain dated kind: a pluralistic post-empiricism (the exact nature of which I left open for now), and a more narrowly focused post-phenomenological approach which regards the former (and/or its main components) as merely another form of the supposedly mutually rejected picture. In sections I and II, I discussed Charles Taylor’s and Hubert Dreyfus’s phenomenological criticisms of Richard Rorty and John McDowell; today I continue with a look at Taylor’s analogous criticism of Donald Davidson. As before, the point is not to reject phenomenological approaches, but instead merely to understand why Davidson looks to Taylor even less like an anti-Cartesian ally than do Rorty and McDowell, and thus why Taylor will not be impressed by a pragmatist strategy of multiple philosophical tools in which Davidsonian semantics plays a major role. Let me also say that in reading a lot of Taylor’s work recently, I was quite impressed with the scope and rigor of his overall project, and I think that what I present as his drastic misreading of Davidson’s philosophy may most likely be detached and discarded without threatening that project. Or so it seems to me at present. Read more »

Last time, in part 1, I distinguished two strategies for combating philosophical modernism of a certain dated kind: a pluralistic post-empiricism (the exact nature of which I left open for now), and a more narrowly focused post-phenomenological approach which regards the former (and/or its main components) as merely another form of the supposedly mutually rejected picture. In sections I and II, I discussed Charles Taylor’s and Hubert Dreyfus’s phenomenological criticisms of Richard Rorty and John McDowell; today I continue with a look at Taylor’s analogous criticism of Donald Davidson. As before, the point is not to reject phenomenological approaches, but instead merely to understand why Davidson looks to Taylor even less like an anti-Cartesian ally than do Rorty and McDowell, and thus why Taylor will not be impressed by a pragmatist strategy of multiple philosophical tools in which Davidsonian semantics plays a major role. Let me also say that in reading a lot of Taylor’s work recently, I was quite impressed with the scope and rigor of his overall project, and I think that what I present as his drastic misreading of Davidson’s philosophy may most likely be detached and discarded without threatening that project. Or so it seems to me at present. Read more »

Monday, September 21, 2020

by Dwight Furrow

A life in which the pleasures of food and drink are not important is missing a crucial dimension of a good life. Food and drink are a constant presence in our lives. They can be a constant source of pleasure if we nurture our connection to them and don’t take them for granted.

A life in which the pleasures of food and drink are not important is missing a crucial dimension of a good life. Food and drink are a constant presence in our lives. They can be a constant source of pleasure if we nurture our connection to them and don’t take them for granted.

Because food and drink are an easily accessible source of pleasure, barring poverty or disease, to care little for them is a moral failure with consequences not only for the self but for others around us. However, to nurture that connection to everyday pleasure requires thought and restraint. Pleasure can be dangerous when pursued without reason and self-control. Addictive pleasures damage us and everyone around us. Addicts, in fact, cannot feel pleasure as readily as the non-addicted and require increasing levels of stimulation to find satisfaction. Addictions and compulsions are pathological and are no model for the genuine pursuit of pleasure. Thus, we need to make a distinction between pleasure that we get from thoughtless, compulsive consumption, and pleasure that is freely chosen. Pleasure freely chosen is actually a good guide to what is good for us and what should matter to us.

This emphasis on freely chosen pleasure is important not only for keeping us healthy but because certain kinds of pleasures are deeply connected to our sense of control and independence. Some of the pleasures in life come from the satisfaction of needs. When we are cold, warm air feels good. When we are hungry even very ordinary food will taste good. But such enjoyment tends to be unfocused and passive. We don’t have to bring our attention or knowledge to the table to enjoy experiences that satisfy basic needs. We are hard-wired to care about them and our response is compelled.

However, many pleasures are not a response to need or deprivation. We have to eat several times a day, but we don’t have to eat well several times a day. Pleasure freely chosen is essential to a good life because it expresses our independence from need. Read more »

Monday, September 14, 2020

by Dave Maier

By the beginning of the 20th century, it had become clear to an influential minority of philosophers that something was badly amiss with modern philosophy. (There had been gripes of innumerable sorts since the beginning of modernity in the 17th century; but our subject today is the present.) “Modern” here means something like “Lockean and/or Cartesian,” where this means … well, it’s not immediately clear what exactly this means, nor what exactly is wrong with it, and therein lies the tale of a good deal of 20th-century philosophy. As with every broken thing, we have two choices: fix it, or throw it out and get a new one; and many philosophers have advertised their projects as doing one or the other. However, as we might expect, unclarity about the old results in corresponding unclarity about the supposedly better new. What’s the actual difference, philosophically speaking, between rehabilitation and replacement?

By the beginning of the 20th century, it had become clear to an influential minority of philosophers that something was badly amiss with modern philosophy. (There had been gripes of innumerable sorts since the beginning of modernity in the 17th century; but our subject today is the present.) “Modern” here means something like “Lockean and/or Cartesian,” where this means … well, it’s not immediately clear what exactly this means, nor what exactly is wrong with it, and therein lies the tale of a good deal of 20th-century philosophy. As with every broken thing, we have two choices: fix it, or throw it out and get a new one; and many philosophers have advertised their projects as doing one or the other. However, as we might expect, unclarity about the old results in corresponding unclarity about the supposedly better new. What’s the actual difference, philosophically speaking, between rehabilitation and replacement?

Let’s start with what two important groups of contemporary anti-modern philosophers (again, let’s leave pre-moderns out of it for today) say about what they’re doing. We can all agree that (in Wittgenstein’s words, but quoted by all and sundry) “a picture held us captive,” and even, in his continuation, that the way it did this was that “it lay in our language and language seemed to repeat it to us endlessly.” That is, it’s not simply a philosophical theory, the conclusion of an argument we have come to regard as unsound. Even in such relatively straightforward cases, of course, there may be plenty of disagreement about how to continue; but here part of our task is not simply to outline a better view, but also to diagnose and escape this characteristic feature of the old one. Such a treatment would explain how such captivity was possible, and how our very language could turn against us, as well as (naturally) what to do about it. Read more »

Monday, August 31, 2020

by Fabio Tollon

Human beings are agents. I take it that this claim is uncontroversial. Agents are that class of entities capable of performing actions. A rock is not an agent, a dog might be. We are agents in the sense that we can perform actions, not out of necessity, but for reasons. These actions are to be distinguished from mere doings: animals, or perhaps even plants, may behave in this or that way by doing things, but strictly speaking, we do not say that they act.

It is often argued that action should be cashed out in intentional terms. Our beliefs, what we desire, and our ability to reason about these are all seemingly essential properties that we might cite when attempting to figure out what makes our kind of agency (and the actions that follow from it) distinct from the rest of the natural world. For a state to be intentional in this sense it should be about or directed towards something other than itself. For an agent to be a moral agent it must be able to do wrong, and perhaps be morally responsible for its actions (I will not elaborate on the exact relationship between being a moral agent and moral responsibility, but there is considerable nuance in how exactly these concepts relate to each other).

In the debate surrounding the potential of Artificial Moral Agency (AMA) this “Standard View” presented above is often a point of contention. The ubiquity of artificial systems in our lives can often lead to us believing that these systems are merely passive instruments. However, this is not always necessarily the case. It is becoming increasingly clear that intuitively “passive” systems, such as recommender algorithms (or even email filter bots), are very receptive to inputs (often by design). Specifically, such systems respond to certain inputs (user search history, etc.) in order to produce an output (a recommendation, etc.). The question that emerges is whether such kinds of “outputs” might be conceived of as “actions”. Moreover, what if such outputs have moral consequences? Might these artificial systems be considered moral agents? This is not to necessarily claim that recommender systems such as YouTube’s are in fact (moral) agents, but rather to think through whether this might be possible (now or in the future). Read more »

Monday, August 24, 2020

by Dwight Furrow

I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality.

I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality.

For many people who drink wine as a commodity beverage, I suppose the platitude “it’s only what’s in the glass matters” is true. But many of the people who talk this way are wine lovers and connoisseurs. For many of them, there is something self-deceptive about this full focus on what is in the glass. Although flavor surely matters, it is not all that matters, and these stories, traditions, and ideologies are central to genuine wine appreciation.

Burnham and Skilleås, in their book The Aesthetics of Wine, engage in a thought experiment that shows the questionable nature of “it’s only what’s in the glass that matters”. They ask us to imagine a scenario in 2030 in which wine science has advanced to such a point that any wine can be thoroughly analyzed, not only into its constituent chemical components (which we can already do up to a point), but with regard to a wine’s full development as well.

Read more »

Monday, August 3, 2020

by Fabio Tollon

In 2019 Buckey Wolf, a 26-year-old man from Seattle, stabbed his brother in the head with a four-foot long sword. He then called the police on himself, admitting his guilt. Another tragic case of mindless violence? Not quite, as there is far more going on in the case of Buckey Wolf: he committed murder because he believed his brother was turning into a lizard. Specifically, a kind of shape-shifting reptile that lives among us and controls world events. If this sounds fabricated, it’s unfortunately not. Over 12 million Americans believe (“know”) that such lizard people exist, and that they are to be found at the highest levels of government, controlling the world economy for their own cold-blooded interests. This reptilian conspiracy theory was first made popular by well-known charlatan David Icke.

What emerged from further investigation into the Wolf murder case was an interesting trend in his YouTube “likes” over the years. Here it was noted that his interests shifted from music to martial arts, fitness, media criticism, firearms and other weapons, and video games. From here it seems Wolf was thrown into the world of alt-right political content.

In a recent paper Alfano et al. study whether YouTube’s recommender system may be responsible for such epistemically retrograde ideation. Perhaps the first case of murder by algorithm? Well, not quite.

In their paper, the authors aim to discern whether technological scaffolding was at least partially involved in Wolf’s atypical cognition. They make use of a theoretical framework known as technological seduction, whereby technological systems try to read user’s minds and predict what they want. In these scenarios, such as when Google uses predictive text, we as users are “seduced” into believing that Google knows our thoughts, especially when we end up following the recommendations of such systems. Read more »

Monday, June 29, 2020

by Dwight Furrow

Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up.

Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up.

Perhaps communication about beauty is not hopeless; we do after all share some responses to beauty. Most everyone agrees the Mona Lisa is beautiful (if you can actually get close enough to enjoy the diminutive painting amidst the hordes at the Louvre). Most everyone agrees that Domaine de la Romanée-Conti makes lovely wine if you can afford a taste. Who would argue with the spectacular coastline view of Cinque Terre from Monterosso?

However, in matters of beauty, disagreements are just as common. As Alexander Nehamas argues, beauty forms communities of like-minded lovers who share an affection for certain works of art and who do find it possible to communicate their obsession. Something escapes the dark tunnels of subjectivity to survive in a clearing where others mingle. But this process excludes people who don’t get it. We are often bored to tears by something that fascinates others. Across that barrier of incomprehension words may well fail. Beauty forms communities of rivals as the scandal surrounding the first performance of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring exemplifies. The contretemps between conventional and natural wine is the latest to divide the wine world. May it not be the last because these conflicts matter and are a symptom of the fundamentally normative response which beauty demands of us. Read more »

Monday, May 4, 2020

by Dwight Furrow

In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative.

In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative.

It’s a peculiarity of the wine community that when designating the highest quality, we sometimes refer to a score assigned by a critic. But that tells us how much that critic liked the wine in comparison to similar wines. It doesn’t tell us why it deserves such a rating. We have criteria to judge wine quality such as complexity, intensity, balance, and focus. But these refer to various dimensions of a wine, not an overall judgement of quality.

Although most wines provide pleasure, some wines are not merely pleasurable. They stand out from the ordinary and have a special claim on our attention. We need a way of describing the depth and meaning of that experience. In the history of aesthetics “beauty” has filled this role as an indicator of remarkable aesthetic quality. It is less frequently used today than in centuries past since many works of modern or contemporary art do not aim at aesthetic pleasure. After the disruptions of 20th Century art, it seems most people in the art world are disillusioned by beauty as if it were a fusty old term genuflecting toward conventions left behind, something false or inflated that reflective people no longer believe in. Read more »

Monday, April 27, 2020

by Dave Maier

The word “interpretivism” suggests to most people a particularly crazy sort of postmodern relativism cum skepticism. If our relations to reality are merely interpretive and perspectival (I will use these terms interchangeably as needed, the idea being that each interpreter has her own distinct perspective on a world not reducible to any single view), our very access to objective facts seems threatened. Nietzsche, for example, famously says that “there are no facts, only interpretations” (a careless misreading, but let’s not get into it here). Fast-forward to Jacques Derrida and the whole lit-crit crew, who claim that everything is a text; and with the triumphantly dismissive reference to that notorious postmodern imp, the game is over. Interpretation is for sissies; let’s get back to doing hard-nosed empirical science (or objective metaphysics).

The word “interpretivism” suggests to most people a particularly crazy sort of postmodern relativism cum skepticism. If our relations to reality are merely interpretive and perspectival (I will use these terms interchangeably as needed, the idea being that each interpreter has her own distinct perspective on a world not reducible to any single view), our very access to objective facts seems threatened. Nietzsche, for example, famously says that “there are no facts, only interpretations” (a careless misreading, but let’s not get into it here). Fast-forward to Jacques Derrida and the whole lit-crit crew, who claim that everything is a text; and with the triumphantly dismissive reference to that notorious postmodern imp, the game is over. Interpretation is for sissies; let’s get back to doing hard-nosed empirical science (or objective metaphysics).

On this account, the opposite of “interpretive” is something like “representational”: our successful beliefs simply get the world right, with no (subjective, open-ended, wishy-washy) interpretation required. This makes sense up to a point. Our beliefs portray the world as being a certain way, not as (primarily) meaningful or enlightening or useful, or whatever is characteristic of our favored interpretations. On the other hand, to distinguish belief from meaning in this way makes it seem as if interpretation does not concern itself with belief or inquiry at all. Yet even if interpretation is not the same as inquiry, or meaning the same as belief, they are – or so we post-Davidsonian pragmatists claim – more closely intertwined than this dichotomous account would indicate.

One way to sort this out is to jump right into it with a close analysis of the notions of meaning and belief in the manner of the later Davidson and Richard Rorty’s frustratingly dodgy use of same. We’ll do more of that later on (he warned); but today I wanted to try another tack. It is generally accepted that history in particular is an interpretive discipline (a “humanity,” not a “science”), yet it is commonly accepted as well that historians deal in facts. If we can see how this conceptual accommodation works in the narrower context, we may be able to transpose it, or something like it, into our larger one. In this post I will set the problem up, leaving you in suspense until next time when I reveal a possible solution. Read more »

Monday, April 20, 2020

by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Democracy is a precious social good. Not only is it necessary for legitimate government, in its absence other crucial social goods – liberty, autonomy, individuality, community, and the like – tend to spoil. It is often inferred from this that a perfectly realized democracy would be utopia, a fully just society of self-governing equals working together for their common good. The flip side of this idea is familiar: the political flaws of a society are ultimately due to its falling short of democracy. The thought runs that as democracy is necessary for securing the other most important social goods, any shortfall in the latter must be due to a deviation from the former. This is what led two of the most influential theorists of democracy of the past century, Jane Addams and John Dewey, to hold that the cure for democracy’s ill is always more and better democracy.

The Addams/Dewey view is committed to the further claim that democracy is an ideal that can be approximated, but never achieved. This addition reminds us that the utopia of a fully realized democracy is forever beyond our reach, an ongoing project of striving to more perfectly democratize our individual and collective lives.

This view is certainly attractive. Trouble lies, however, in making the democratic ideal concrete enough to serve as a guide to real-world politics without thereby deflating it of its ennobling character. Typically, as the ideal is made more explicit, one finds that it presumes capacities that go far beyond the capabilities of ordinary citizens. It turns out that democracy isn’t only out of our reach, it’s also not for us. Read more »

Monday, March 9, 2020

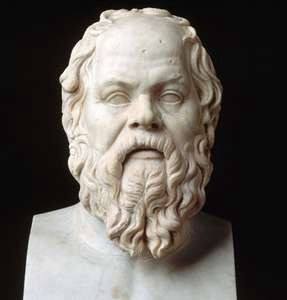

Socrates, snub-nosed, wall-eyed, paunchy, squat,

Socrates, snub-nosed, wall-eyed, paunchy, squat,

stood before his accusers and confessed

to being a gift from god—a gadfly, a pest

sent to save the city from moral rot

by stinging it out of its torpor. He was not

believed. The Athenians could not think themselves blessed

to be bitten by philosophy. Unimpressed,

they silenced their gadfly with a judicial swat.

Today, we keep our would-be pests inside

a jar, contentedly droning away from the world.

But should one ever get free and buzz about seeking

to sink a sharp question into society’s hide,

then the nation yelps, newspapers are furled,

and packs of good citizens clamber up flailing and shrieking.

by Emrys Westacott

by Dwight Furrow

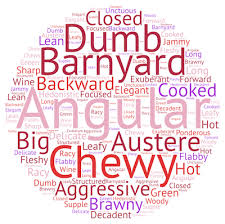

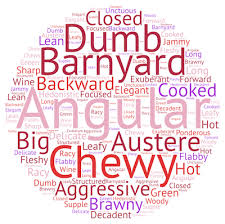

Research by linguists into wine metaphors have identified several source domains that help wine writers describe the faint and ephemeral features of poetry in a glass. “Wine is a building”, “wine is piece of cloth”, and especially “wine is a person” are a few of the rich diversity of potential likenesses that might uncover facets of a wine. There are after all many ways of being a body or a person with new variants continuously on offer. But how do writers identify, within these source domains, which likenesses will be compelling and how do readers come to understand what a metaphor means? Identifying source domains for wine metaphors must be supplemented by an account of how interpretation works.

Research by linguists into wine metaphors have identified several source domains that help wine writers describe the faint and ephemeral features of poetry in a glass. “Wine is a building”, “wine is piece of cloth”, and especially “wine is a person” are a few of the rich diversity of potential likenesses that might uncover facets of a wine. There are after all many ways of being a body or a person with new variants continuously on offer. But how do writers identify, within these source domains, which likenesses will be compelling and how do readers come to understand what a metaphor means? Identifying source domains for wine metaphors must be supplemented by an account of how interpretation works.

Given the importance of variation and distinctiveness in wine appreciation and the need for linguistic innovation to capture these dimensions, theories of metaphor that explicitly link metaphor to the exercise of imagination will be most useful. The use of metaphor in wine language looks backward to conventional, entrenched descriptions while looking forward in order to capture the emergence of innovative taste profiles that require linguistic imagination.

To add more complexity to the mix, the use of metaphor in wine language serves two broad purposes that are sometimes opposed. On the one hand writers use metaphor to communicate an accurate description of the wine they’re tasting, especially by conveying the holistic properties such as elegance, intensity, or balance. On the other hand, metaphor expresses the remarkable experiences of a wine that wine importer Terry Theise calls “sublime”. “Some wines” he writes, “…are so haunting and stirring that they bypass our entire analytical faculty and fill us with image and feeling”. Read more »

Monday, March 2, 2020

by Dave Maier

Last month in this space I posted the notes to my latest ambient mix, and you may have noticed at that time that in those notes I slagged my own composition “Nothing really” – even in its title! – as being nothing much, and promised to explain later. Here I fulfill that promise.

If you listen to that track as featured in the mix, my judgment may seem a little harsh. The track is on the static side, but that’s hardly a fault in the context: the textures are lovely, and there’s plenty of movement; and at under four minutes it can’t really be said to overstay its welcome. A minor work, perhaps, but as a brief linking interlude it works perfectly well. So what’s the problem?

If you listen to that track as featured in the mix, my judgment may seem a little harsh. The track is on the static side, but that’s hardly a fault in the context: the textures are lovely, and there’s plenty of movement; and at under four minutes it can’t really be said to overstay its welcome. A minor work, perhaps, but as a brief linking interlude it works perfectly well. So what’s the problem?

Well, I’ll tell you. Here’s how I made it: first, I fired up one of my many synthesizers (here a software synth called Aparillo, purchased in a discounted bundle with a bunch of other entirely out of control plug-ins from the same developer on this last Black Friday). Then I selected a particular preset supplied by the developer. Then – after adjusting the routing a bit, so that I would record sound rather than MIDI – I clicked Record on my DAW and pressed a single key on my MIDI controller (G4, maybe), and held that key down for about four minutes. There, finished! I didn’t do any further processing (synths tend to have built-in effects now, so that lush reverb is already there in the preset) or mastering or anything. Nor did I tweak the preset’s parameters in any way. It took about five minutes in total, most of which, again, was spent holding the key down and listening.

My questions here seem at first to be of two distinct kinds: conceptual/ontological and evaluative. What is “Nothing really”? Is it a musical composition, or perhaps a composition of another kind? Who composed it? and what determines the answers to these questions? And are they really distinct from evaluative questions, the main such question obviously being: how good (or bad) is it? Here too, what determines that? Read more »

Monday, February 10, 2020

by Dwight Furrow

The wine community is often accused of being snobby and elitist. The language used to describe wine is one source of this innuendo. Although most people have become accustomed to the fruit descriptors used in wine reviews, when wine writers wax poetic by describing wines as “graphite mixed with pâte de fruit”, even some wine professionals get up in arms.

The wine community is often accused of being snobby and elitist. The language used to describe wine is one source of this innuendo. Although most people have become accustomed to the fruit descriptors used in wine reviews, when wine writers wax poetic by describing wines as “graphite mixed with pâte de fruit”, even some wine professionals get up in arms.

The general complaint is that metaphorical attributions are too subjective and ambiguous. When a wine is described as “a streetwalker” or “sinewy” it’s unclear to some readers what features of the wine are being described. The further inference drawn is that these are just attempts to make wine descriptions less monotonous or call attention to the writer’s talent for verbal calisthenics without getting at something important about the wine.

There are several things to say about these objections. Read more »

Monday, January 13, 2020

by Dwight Furrow

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists went so far as to call wine writers “bullshit artists”. (The feeling is mutual.)

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists went so far as to call wine writers “bullshit artists”. (The feeling is mutual.)

Even the sommelier-trained author of the bestselling book Cork Dork, Bianca Bosker, has reservations about the accuracy of such language. After taking writers to task for using terms such as “sinewy” and “broad-shouldered” she writes: “It seems possible that what we “taste” in a fine wine isn’t so much its flavor as the qualities of good taste that we hope it will impart to us.” She seems to be suggesting that wine writers just make stuff up to sound impressive.

The general objection is that these descriptors are metaphorical and are therefore too subjective and ambiguous to give readers an accurate, verbal portrayal of the wine. However, these complaints are tilting at windmills. Read more »

Monday, November 18, 2019

by Dwight Furrow

Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make.

Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make.

Vitality, in a related sense, is also an organoleptic property of a wine—it can be tasted. When we taste them, quality wines exhibit constant variation, dynamic development, and a felt potency, a sensation of expansion, contraction, and velocity that contribute to a wine’s distinctive personality. These features are much prized among contemporary wine lovers who seek freshness and tension in their wines. Thus, wine expresses vitality both as an ontological condition and as a collection of aesthetic properties.

However, this expression of vitality in both senses is fading in aged wines. In aged wines, freshness and dynamism can be tasted but only as vestigial as the fruit dries out and recedes behind leather, nut and earthy aromas. Appreciation of aged wines (at least those wines worthy of being aged) requires that we see delicacy, shyness, restraint, composure, equanimity, imperfection, and the ephemeral as normative. Read more »

Monday, November 11, 2019

by Dave Maier

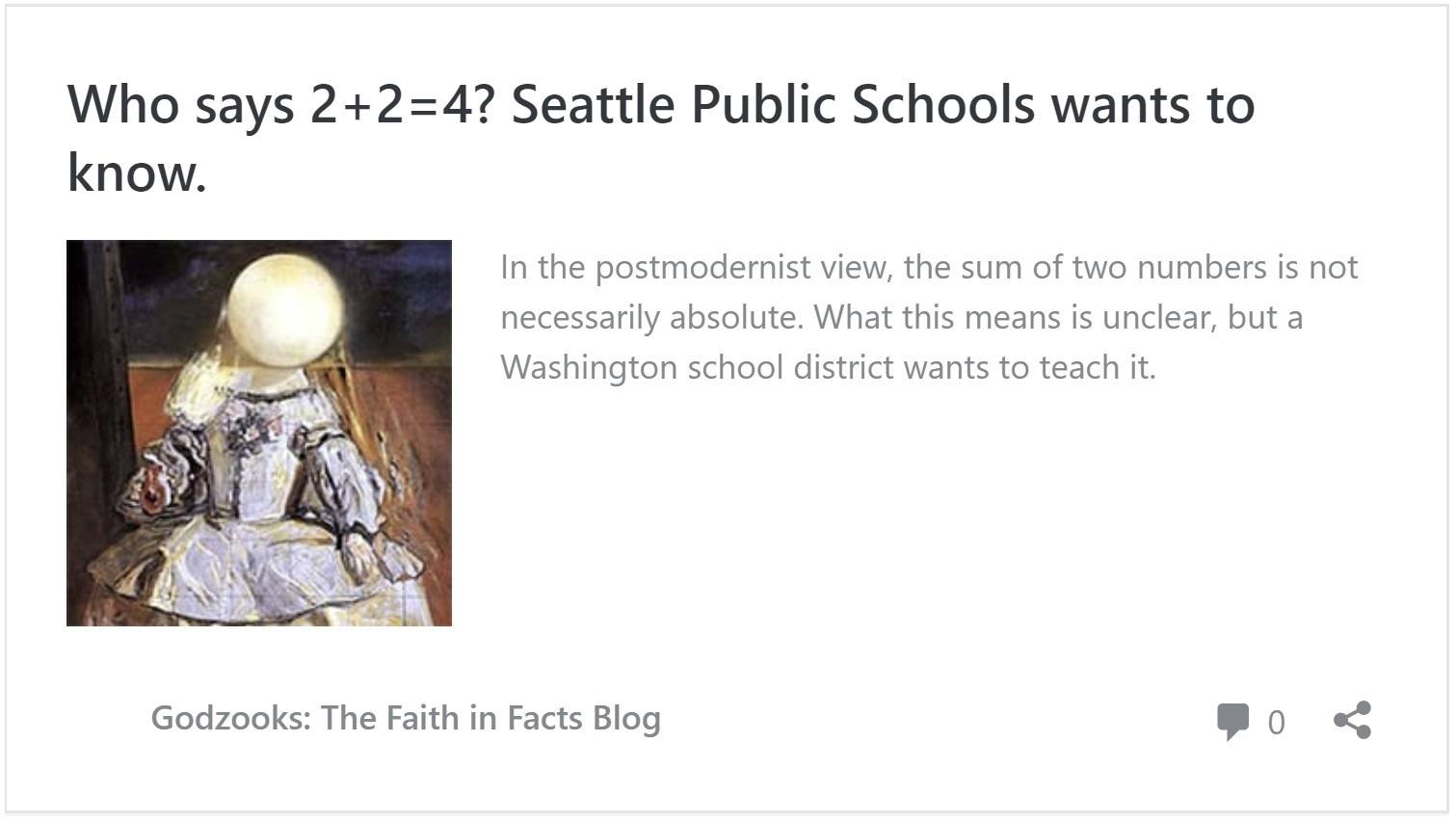

The blog post screams: “If you think 2 + 2 always equals 4, you’re a racist oppressor.”

The blog post screams: “If you think 2 + 2 always equals 4, you’re a racist oppressor.”

It then proceeds to attribute this ghastly sentiment to the Seattle Public School district, on the basis of a preliminary document for a proposed curriculum in “Math Ethnic Studies.” Other critics of this pseudo-educational abomination are cited; math, they agree, is an area “which all people should be able to view as objectively settled.” To doubt this is to fall prey to the worst postmodern relativism and skepticism. And so on, in familiar fashion.

I’m not here to defend the Seattle Public School district specifically, nor multiculturalism in general, nor postmodern relativism and skepticism, for that matter. But to respond to the first two with the same tired 90s-era pomo-bashing (“Apparently math is now subjective,” mocks one critic) is to combine sloppy interpretive procedure with half-baked folk philosophy. Let’s put the latter aside for now and start with the former. Read more »

Monday, October 21, 2019

by Dwight Furrow

Among the best books I’ve read about wine are the two by wine importer Terry Theise. Reading Between the Wines is a thoroughly enjoyable account of his life in wine and a passionate defense of artisanality. But it’s his most recent book What Makes a Wine Worth Drinking: In Praise of the Sublime that really gets my philosophical juices flowing.

Among the best books I’ve read about wine are the two by wine importer Terry Theise. Reading Between the Wines is a thoroughly enjoyable account of his life in wine and a passionate defense of artisanality. But it’s his most recent book What Makes a Wine Worth Drinking: In Praise of the Sublime that really gets my philosophical juices flowing.

Long celebrated for his portfolio of mostly German and Austrian wines as well as grower Champagne, in these two books he articulates a sophisticated, yet non-theoretical philosophy of wine and introduces a badly needed corrective to our fatally constrained and often vulgar approach to wine that confuses marketing with aesthetics. But like any work of philosophy, this book raises profound questions. Here are a few quotes that I think raise the most important questions we need to answer.

Great wine can induce reverie; I imagine most of us would concur. But the cultivation of reverie is also the best approach to understanding fine wine.

What is it about us and what is it about wine that induces a dream-like state, that sets the imagination in motion? Why does wine’s capacity to induce reverie help us understand fine wine?

If wine had turned out to be merely sensual I think for me its joys would have been transitory. I’d have done the “wine thing” for a certain number of years and gone on to something else. What continued to drive me, and what drives many of us, is curiosity, pleasure in surprise, and those elusive, incandescent moments of meaning—the sense that some truth, normally obscure, was being revealed.

How can a beverage reveal truths? What kind of truth is this and how would we know we have it? Read more »

Monday, September 23, 2019

by Dwight Furrow

It’s fashionable to criticize wine critics for a variety of sins: they’re biased, their scores don’t mean anything, and their jargon is unintelligible according to the critics of critics. Shouldn’t we just drink what we like? Who cares what critics think? In fact, whether the object is literature, painting, film, music, or wine, criticism is important for establishing evaluative standards and maintaining a dialogue about what is worth experiencing and why. The following is an account of how wine criticism aids wine appreciation by way of providing an account of wine appreciation.

It’s fashionable to criticize wine critics for a variety of sins: they’re biased, their scores don’t mean anything, and their jargon is unintelligible according to the critics of critics. Shouldn’t we just drink what we like? Who cares what critics think? In fact, whether the object is literature, painting, film, music, or wine, criticism is important for establishing evaluative standards and maintaining a dialogue about what is worth experiencing and why. The following is an account of how wine criticism aids wine appreciation by way of providing an account of wine appreciation.

Wine critics engage in a variety of activities. They evaluate wines by saying whether they are good or bad, often in order to advise readers about which wines they should purchase or seek to experience. Via their tasting notes, they guide their reader’s perceptions of a wine getting them to taste something they otherwise might have missed. Critics explain winemaking and viticultural practices, feature winemakers and explain how their inspiration or approach to winemaking influences their wines. They discuss styles of winemaking, changes in those styles as they occur, and new developments in the wine world. They discuss the quality of vintages, the characteristics of varietals and wine regions, and describe their own reactions to a wine.

The most plausible goal that ties all these activities together is that the critic aims to help her readers appreciate the wines about which she writes. Wine criticism is not just loosely related to wine appreciation; the purpose of wine criticism is to aid appreciation and thus we need an account of what it means to appreciate a wine. Read more »

Monday, September 2, 2019

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

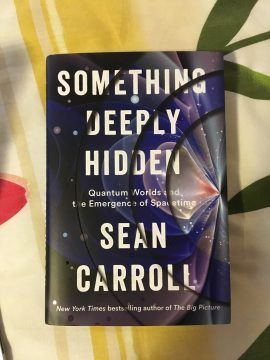

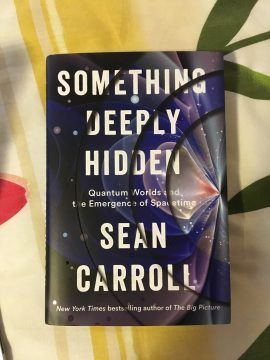

For me, a highlight of an otherwise ill-spent youth was reading mathematician John Casti’s fantastic book “Paradigms Lost“. The book came out in the late 1980s and was gifted to my father who was a professor of economics by an adoring student. Its sheer range and humor had me gripped from the first page. Its format is very unique – Casti presents six “big questions” of science in the form of a courtroom trial, advocating arguments for the prosecution and the defense. He then steps in as jury to come down on one side or another. The big questions Casti examines are multidisciplinary and range from the origin of life to the nature/nurture controversy to extraterrestrial intelligence to, finally, the meaning of reality as seen through the lens of the foundations of quantum theory. Surprisingly, Casti himself comes down on the side of the so-called many worlds interpretation (MWI) of quantum theory, and ever since I read “Paradigms Lost” I have been fascinated by this analysis.

For me, a highlight of an otherwise ill-spent youth was reading mathematician John Casti’s fantastic book “Paradigms Lost“. The book came out in the late 1980s and was gifted to my father who was a professor of economics by an adoring student. Its sheer range and humor had me gripped from the first page. Its format is very unique – Casti presents six “big questions” of science in the form of a courtroom trial, advocating arguments for the prosecution and the defense. He then steps in as jury to come down on one side or another. The big questions Casti examines are multidisciplinary and range from the origin of life to the nature/nurture controversy to extraterrestrial intelligence to, finally, the meaning of reality as seen through the lens of the foundations of quantum theory. Surprisingly, Casti himself comes down on the side of the so-called many worlds interpretation (MWI) of quantum theory, and ever since I read “Paradigms Lost” I have been fascinated by this analysis.

So it was with pleasure and interest that I came across Sean Carroll’s book that also comes down on the side of the many worlds interpretation. The MWI goes back to the very invention of quantum theory by pioneering physicists like Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger. As exemplified by Heisenberg’s famous uncertainty principle, quantum theory signaled a striking break with reality by demonstrating that one can only talk about the world only probabilistically. Contrary to common belief, this does not mean that there is no precision in the predictions of quantum mechanics – it’s in fact the most accurate scientific framework known to science, with theory and experiment agreeing to several decimal places – but rather that there is a natural limit and fuzziness in how accurately we can describe reality. As Bohr put it, “physics does not describe reality; it describes reality as subjected to our measuring instruments and observations.” This is actually a reasonable view – what we see through a microscope and telescope obviously depends on the features of that particular microscope or telescope – but quantum theory went further, showing that the uncertainty in the behavior of the subatomic world is an inherent feature of the natural world, one that doesn’t simply come about because of uncertainty in experimental observations or instrument error. Read more »

Last time, in part 1, I distinguished two strategies for combating philosophical modernism of a certain dated kind: a pluralistic post-empiricism (the exact nature of which I left open for now), and a more narrowly focused post-phenomenological approach which regards the former (and/or its main components) as merely another form of the supposedly mutually rejected picture. In sections I and II, I discussed Charles Taylor’s and Hubert Dreyfus’s phenomenological criticisms of Richard Rorty and John McDowell; today I continue with a look at Taylor’s analogous criticism of Donald Davidson. As before, the point is not to reject phenomenological approaches, but instead merely to understand why Davidson looks to Taylor even less like an anti-Cartesian ally than do Rorty and McDowell, and thus why Taylor will not be impressed by a pragmatist strategy of multiple philosophical tools in which Davidsonian semantics plays a major role. Let me also say that in reading a lot of Taylor’s work recently, I was quite impressed with the scope and rigor of his overall project, and I think that what I present as his drastic misreading of Davidson’s philosophy may most likely be detached and discarded without threatening that project. Or so it seems to me at present. Read more »

Last time, in part 1, I distinguished two strategies for combating philosophical modernism of a certain dated kind: a pluralistic post-empiricism (the exact nature of which I left open for now), and a more narrowly focused post-phenomenological approach which regards the former (and/or its main components) as merely another form of the supposedly mutually rejected picture. In sections I and II, I discussed Charles Taylor’s and Hubert Dreyfus’s phenomenological criticisms of Richard Rorty and John McDowell; today I continue with a look at Taylor’s analogous criticism of Donald Davidson. As before, the point is not to reject phenomenological approaches, but instead merely to understand why Davidson looks to Taylor even less like an anti-Cartesian ally than do Rorty and McDowell, and thus why Taylor will not be impressed by a pragmatist strategy of multiple philosophical tools in which Davidsonian semantics plays a major role. Let me also say that in reading a lot of Taylor’s work recently, I was quite impressed with the scope and rigor of his overall project, and I think that what I present as his drastic misreading of Davidson’s philosophy may most likely be detached and discarded without threatening that project. Or so it seems to me at present. Read more »

A life in which the pleasures of food and drink are not important is missing a crucial dimension of a good life. Food and drink are a constant presence in our lives. They can be a constant source of pleasure if we nurture our connection to them and don’t take them for granted.

A life in which the pleasures of food and drink are not important is missing a crucial dimension of a good life. Food and drink are a constant presence in our lives. They can be a constant source of pleasure if we nurture our connection to them and don’t take them for granted. By the beginning of the 20th century, it had become clear to an influential minority of philosophers that something was badly amiss with modern philosophy. (There had been gripes of innumerable sorts since the beginning of modernity in the 17th century; but our subject today is the present.) “Modern” here means something like “Lockean and/or Cartesian,” where this means … well, it’s not immediately clear what exactly this means, nor what exactly is wrong with it, and therein lies the tale of a good deal of 20th-century philosophy. As with every broken thing, we have two choices: fix it, or throw it out and get a new one; and many philosophers have advertised their projects as doing one or the other. However, as we might expect, unclarity about the old results in corresponding unclarity about the supposedly better new. What’s the actual difference, philosophically speaking, between rehabilitation and replacement?

By the beginning of the 20th century, it had become clear to an influential minority of philosophers that something was badly amiss with modern philosophy. (There had been gripes of innumerable sorts since the beginning of modernity in the 17th century; but our subject today is the present.) “Modern” here means something like “Lockean and/or Cartesian,” where this means … well, it’s not immediately clear what exactly this means, nor what exactly is wrong with it, and therein lies the tale of a good deal of 20th-century philosophy. As with every broken thing, we have two choices: fix it, or throw it out and get a new one; and many philosophers have advertised their projects as doing one or the other. However, as we might expect, unclarity about the old results in corresponding unclarity about the supposedly better new. What’s the actual difference, philosophically speaking, between rehabilitation and replacement?

I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality.

I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality.

Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up.

Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up. In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative.

In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative. The word “interpretivism” suggests to most people a particularly crazy sort of postmodern relativism cum skepticism. If our relations to reality are merely interpretive and perspectival (I will use these terms interchangeably as needed, the idea being that each

The word “interpretivism” suggests to most people a particularly crazy sort of postmodern relativism cum skepticism. If our relations to reality are merely interpretive and perspectival (I will use these terms interchangeably as needed, the idea being that each

Socrates, snub-nosed, wall-eyed, paunchy, squat,

Socrates, snub-nosed, wall-eyed, paunchy, squat, Research by linguists

Research by linguists If you listen to that track as featured in the mix, my judgment may seem a little harsh. The track is on the static side, but that’s hardly a fault in the context: the textures are lovely, and there’s plenty of movement; and at under four minutes it can’t really be said to overstay its welcome. A minor work, perhaps, but as a brief linking interlude it works perfectly well. So what’s the problem?

If you listen to that track as featured in the mix, my judgment may seem a little harsh. The track is on the static side, but that’s hardly a fault in the context: the textures are lovely, and there’s plenty of movement; and at under four minutes it can’t really be said to overstay its welcome. A minor work, perhaps, but as a brief linking interlude it works perfectly well. So what’s the problem? The wine community is often accused of being snobby and elitist. The language used to describe wine is one source of this innuendo. Although most people have become accustomed to the fruit descriptors used in wine reviews, when wine writers wax poetic by describing wines as “graphite mixed with pâte de fruit”, even

The wine community is often accused of being snobby and elitist. The language used to describe wine is one source of this innuendo. Although most people have become accustomed to the fruit descriptors used in wine reviews, when wine writers wax poetic by describing wines as “graphite mixed with pâte de fruit”, even  Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists  Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make.

Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make. The blog post screams: “If you think 2 + 2 always equals 4, you’re a racist oppressor.”

The blog post screams: “If you think 2 + 2 always equals 4, you’re a racist oppressor.” Among the best books I’ve read about wine are the two by wine importer Terry Theise.

Among the best books I’ve read about wine are the two by wine importer Terry Theise.  It’s fashionable to criticize wine critics for a variety of sins: they’re biased, their scores don’t mean anything, and their jargon is unintelligible according to the critics of critics. Shouldn’t we just drink what we like? Who cares what critics think? In fact, whether the object is literature, painting, film, music, or wine, criticism is important for establishing evaluative standards and maintaining a dialogue about what is worth experiencing and why. The following is an account of how wine criticism aids wine appreciation by way of providing an account of wine appreciation.

It’s fashionable to criticize wine critics for a variety of sins: they’re biased, their scores don’t mean anything, and their jargon is unintelligible according to the critics of critics. Shouldn’t we just drink what we like? Who cares what critics think? In fact, whether the object is literature, painting, film, music, or wine, criticism is important for establishing evaluative standards and maintaining a dialogue about what is worth experiencing and why. The following is an account of how wine criticism aids wine appreciation by way of providing an account of wine appreciation. For me, a highlight of an otherwise ill-spent youth was reading mathematician John Casti’s fantastic book “

For me, a highlight of an otherwise ill-spent youth was reading mathematician John Casti’s fantastic book “