by David Kordahl

The science lab and the theory suite

If you spend any time doing science, you might notice that some things change when you close the door to the lab and walk into the theory suite.

In the laboratory, surprising things happen, no doubt about it. Depending on the type of lab you’re working in, you might see liquid nitrogen boiling out from a container, solutions changing color only near their surfaces, or microorganisms unexpectedly mutating. But once roughly the same thing happens a few times in a row, the conventional scientific attitude is to suppose that you can make sense of these observations. Sure, you can still expect a few outliers that don’t follow the usual trends, but there’s nothing in the laboratory that forces one to take any strong metaphysical positions. The surprises, instead, are of the sort that might lead someone to ask, Can I see that again? What conditions would allow this surprise to reoccur?

Of course, the ideas discussed back in the theory suite are, in some indirect way, just codified responses to old observational surprises. But scientists—at least, young scientists—rarely think in such pragmatic terms. Most young scientists are cradle realists, and start out with the impression that there is quite a cozy relationship between the entities they invoke in the theory suite and the observations they make back in the lab. This can be quite confusing, since connecting theory to observation is rarely so straightforward as simply calculating from first principles.

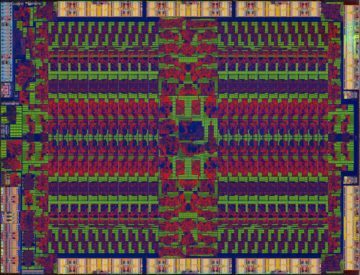

The types of experiments I’ve had been able to observe most closely involve electron microscopes. For many cases where electron microscopes are involved, workers will use quantum models to describe the observations. I’ve written about quantum models a few times before, but I haven’t discussed much about how quantum physics models differ from their classical physics counterparts. Last summer, I worked out a simple, concrete example in detail, and this column will discuss the upshot of that, leaving out the details. If you’ve ever wondered, how exactly do quantum models work?—or even if you haven’t wondered, but are wondering now that I mention it—well, read on. Read more »

When we speak about identity, we usually have in mind the various social categories we occupy—gender categories, nationality, or racial categories being the most prominent. But none of these general characteristics really define us as individuals. Each of us falls into various categories but so does everyone else. To say I’m a straight white male puts me in a bucket with millions of others. To add my nationality and profession only narrows it down a bit.

When we speak about identity, we usually have in mind the various social categories we occupy—gender categories, nationality, or racial categories being the most prominent. But none of these general characteristics really define us as individuals. Each of us falls into various categories but so does everyone else. To say I’m a straight white male puts me in a bucket with millions of others. To add my nationality and profession only narrows it down a bit.

Does philosophy have anything to tell us about problems we face in everyday life? Many ancient philosophers thought so. To them, philosophy was not merely an academic discipline but a way of life that provided distinctive reasons and motivations for living well. Some contemporary philosophers have been inspired by these ancient sources giving new life to this question about philosophy’s practical import.

Does philosophy have anything to tell us about problems we face in everyday life? Many ancient philosophers thought so. To them, philosophy was not merely an academic discipline but a way of life that provided distinctive reasons and motivations for living well. Some contemporary philosophers have been inspired by these ancient sources giving new life to this question about philosophy’s practical import.

Today “skepticism” has two related meanings. In ordinary language it is a behavioral disposition to withhold assent to a claim until sufficient evidence is available to judge the claim true or false. This skeptical disposition is central to scientific inquiry, although financial incentives and the attractions of prestige render it inconsistently realized. In a world increasingly afflicted with misinformation, disinformation, and outright lies we could use more skepticism of this sort.

Today “skepticism” has two related meanings. In ordinary language it is a behavioral disposition to withhold assent to a claim until sufficient evidence is available to judge the claim true or false. This skeptical disposition is central to scientific inquiry, although financial incentives and the attractions of prestige render it inconsistently realized. In a world increasingly afflicted with misinformation, disinformation, and outright lies we could use more skepticism of this sort.

If philosophy is not only an academic, theoretical discipline but a way of life, as many Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers thought, one way of evaluating a philosophy is in terms of the kind of life it entails.

If philosophy is not only an academic, theoretical discipline but a way of life, as many Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers thought, one way of evaluating a philosophy is in terms of the kind of life it entails.

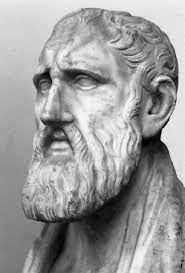

One of the more remarkable developments in popular philosophy over the past 20 years is the rebirth of stoicism. Stoicism was an ancient Greek and Roman philosophy founded around 300 BCE by the merchant Zeno of Citium, in what is now Cyprus. Although, contemporary professional philosophers occasionally discuss Stoicism as a form of virtue ethics, most consider it to be a minor philosophical movement in the history of philosophy with limited influence. Yet it has captured the attention of the non-professional philosophical world with many websites and online communities devoted to its practice.

One of the more remarkable developments in popular philosophy over the past 20 years is the rebirth of stoicism. Stoicism was an ancient Greek and Roman philosophy founded around 300 BCE by the merchant Zeno of Citium, in what is now Cyprus. Although, contemporary professional philosophers occasionally discuss Stoicism as a form of virtue ethics, most consider it to be a minor philosophical movement in the history of philosophy with limited influence. Yet it has captured the attention of the non-professional philosophical world with many websites and online communities devoted to its practice.

For many of the ancient philosophers that we still read today, philosophy was not only an intellectual pursuit but a way of life, a rigorous pursuit of wisdom that can guide us through the difficult decisions and battle for self-control that characterize a human life. That view of philosophy as a practical guide faded throughout much of modern history as the idea of a “way of life” was deemed a matter of personal preference and philosophical ethics became a study of how we justify right action. But with the recognition that philosophy might speak to broader concerns than those that get a hearing in academia, this idea of philosophy as a way of life

For many of the ancient philosophers that we still read today, philosophy was not only an intellectual pursuit but a way of life, a rigorous pursuit of wisdom that can guide us through the difficult decisions and battle for self-control that characterize a human life. That view of philosophy as a practical guide faded throughout much of modern history as the idea of a “way of life” was deemed a matter of personal preference and philosophical ethics became a study of how we justify right action. But with the recognition that philosophy might speak to broader concerns than those that get a hearing in academia, this idea of philosophy as a way of life

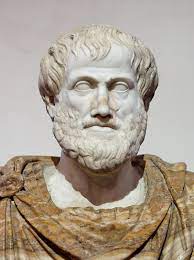

Among the ideas in the history of philosophy most worthy of an eye-roll is Aristotle’s claim that the study of metaphysics is the highest form of eudaimonia (variously translated as “happiness” or “flourishing”) of which human beings are capable. The metaphysician is allegedly happier than even the philosopher who makes a well-lived life the sole focus of inquiry. “Arrogant,” self-serving,” and “implausible” come immediately to mind as a first response to the argument. It’s not at all obvious that philosophers, let alone metaphysicians, are happier than anyone else nor is it obvious why the investigation of metaphysical matters is more joyful or conducive to flourishing than the investigation of other subjects.

Among the ideas in the history of philosophy most worthy of an eye-roll is Aristotle’s claim that the study of metaphysics is the highest form of eudaimonia (variously translated as “happiness” or “flourishing”) of which human beings are capable. The metaphysician is allegedly happier than even the philosopher who makes a well-lived life the sole focus of inquiry. “Arrogant,” self-serving,” and “implausible” come immediately to mind as a first response to the argument. It’s not at all obvious that philosophers, let alone metaphysicians, are happier than anyone else nor is it obvious why the investigation of metaphysical matters is more joyful or conducive to flourishing than the investigation of other subjects.