by Brooks Riley

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Brooks Riley

by Eric J. Weiner

The delicate balance of mentoring someone is not creating them in your own image, but giving them the opportunity to create themselves. — Steven Spielberg

All mentors teach, but not all teachers become mentors. Mentors nurture, guide, teach, support, protect, challenge, help, listen, defend, critique, and unselfishly share their knowledge, time, and skills with their protégés. The mentor is father, mother, friend, platonic lover, healer, advisor, advocate, confidant, translator, and intellectual broker. The mentor/protégé relationship is not equal nor does it trouble itself with questions of equity. But it is consensual in that the mentor and protégé must both want and agree to the normative demands of the relationship. This does not mean the protégé might not resist, question or challenge his/her mentor. On the contrary, conflict between a mentor and protégé is normal and necessary. But instead of walking away from the relationship because of the tensions and conflicts that might arise, the mentor and protégé work them out, lean into them and, as a consequence, become stronger and more deeply connected. The one hold that is barred from the mentor/protégé relationship is disrespect.[i] Without mutual respect the relationship cannot function as it should and will dissolve, often bitterly.

I have been fortunate to have several mentors throughout my life that have taken me under their care, generously shared their knowledge and time, courageously challenged me when I was wrongheaded, and opened themselves up to my endless inquiries. They showed considerable patience in the face of my tenacious ignorance, insecurity/arrogance, quickness to rage, and tendency toward theoretical abstraction, paralyzing hypocrisy, and self-righteous indignation. My mentors, in different ways, deeply affected who I am today, although I take full responsibility for the tragic flaws and continuing struggles with the aforementioned dispositions of character that still burden me and those closest to me. In the spirit of auld lang syne and from the tradition of Hip-Hop–to look back to pay it forward–I want to give a shout-out to each of my mentors, some of whom I still depend on to set me straight if/when I inevitably go off the rails: (in alphabetical order) Elizabeth “Libby” Fay, Henry Giroux, Jaime Grinberg, Donaldo Macedo, Cindy Onore, and Pat Shannon. Read more »

by Michael Liss

Adlai Stevenson, in the concession speech he gave after being thoroughly routed by Ike in the 1952 Election, referenced a possibly apocryphal quote by Abraham Lincoln: “He felt like a little boy who had stubbed his toe in the dark. He said that he was too old to cry, but it hurt too much to laugh.”

Adlai Stevenson, in the concession speech he gave after being thoroughly routed by Ike in the 1952 Election, referenced a possibly apocryphal quote by Abraham Lincoln: “He felt like a little boy who had stubbed his toe in the dark. He said that he was too old to cry, but it hurt too much to laugh.”

Stevenson got over it sufficiently to try again in 1956 (he stubbed a different toe, even harder), but the point remains the same. Losing stinks. Having to be gracious about it also stinks. So, it’s not unreasonable to assume that having to be gracious about it when you are the incumbent stinks even more, but that’s the job. The country has made a choice, and (let us keep our eyes firmly planted in the past for now), it is incumbent on the incumbent to cooperate, even if it is not required that he suddenly adopt the policies of his soon-to-be successor.

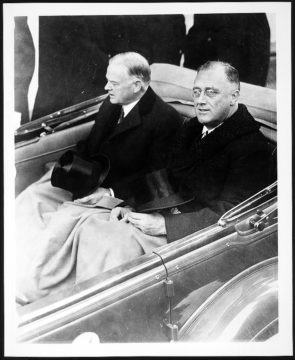

Last month, I wrote about the fraught transition from Buchanan to Lincoln, which ended with secession and, shortly after Lincoln’s Inauguration, led to the Civil War. Lincoln, and all that he represented, was clearly anathema to Buchanan, who, when he got up the nerve, acted accordingly. This month, I’m turning to the potent clashes of ideology and ego that went into the transition between Herbert Hoover and Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Hoover was once one of the most admired men in the world. He had earned that through his service in World War I, first by aiding thousands of American tourists stranded in Europe, then, as Chairman of the Commission for Relief in Belgium, by helping to feed millions of people. He returned home in 1917 to take a role as Food Administrator for the United States, and, without much statutory authority, accomplished logistical feats on food supply and conservation. Woodrow Wilson sent him back to Europe to head the American Relief Administration, where he led economic restoration efforts after the war’s end, distributed 20 million tons of food to tens of millions across the continent, rebuilt communications, and organized shipping on sea and by rail. His efforts were so extraordinary that streets were named after him in several European cities. Read more »

by Bill Murray

In this column I write about international travel, especially travel to less understood parts of the world. This month, with such travel still a wee bit constrained, we start a two-part look back at Sri Lanka, April/May 1999:

There are certain things a guidebook ought to level with you about right up front, before gushing about the exotic culture, pristine sandy beaches and friendly people. Number one, page one, straight flat out:

YOU ARE FLYING INTO A COUNTRY THAT CAN’T KEEP THE ROAD TO ITS ONE INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT PAVED, AND LINES THE ROAD IN AND OUT WITH BOYS WITH NO FACIAL HAIR HOLDING MACHINE GUNS.

Lurching into and out of potholes on the road from the airport to the beach, dim yellow headlights illuminated scrawny street dogs sneering from the road, teeth in road kill. Mirja and I took the diplomatic approach and decided, let’s see what it looks like in the morning.

•••••

The fishing fleet already trolled off the Negombo shore in the gray before dawn. The last tardy catamaran, sail full-billowed, flew out to join the rest. Read more »

Music as a prelude to Jerry Seinfeld

I started trumpet lessons when I was ten years old or so. After about two years or so my lessons were drawn from Jean-Baptiste Arban’s Complete Conservatory Method for Trumpet, which dates from the middle of the 19th century and is the central method book in ‘legit’ trumpet pedagogy. Near the end, before a series of virtuoso solos, I read words which, in retrospect, are at the center of my interest in Jerry Seinfeld’s observations on his craft. Arban observed:

There are things which appear clear enough when uttered viva voce but which cannot be committed to paper without engendering confusion and obscurity, or without appearing puerile.

There are other things of so elevated and subtle a nature that neither speech nor writing can clearly explain them. They are felt, they are conceived, but they are not to be explained; and yet these things constitute the elevated style, the grande ecole, which it is my ambition to institute for the cornet, even as they already exist for singing and the various kinds of instruments.

What, you may ask, does this grande ecole have to do with standup comedy? Everything and nothing.

Cool your jets. Read more »

by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

In his victory speech President-elect Joe Biden declared that “this is the time to heal America,” urging citizens to “come together,” “give each other a chance,” and “stop treating opponents as enemies.” He added that partisanship “is not due to some mysterious force,” but is rather “a choice we make.” To be sure, that partisanship is a choice doesn’t mean it’s easily overcome. So, Biden offered a plan. He proposed that we “see each other again” and “listen to each other again.”

In calling for the healing of our partisan divisions, Biden struck a popular note. Americans across the spectrum tend to agree that our politics has become dangerously toxic and uncivil. We say we want more compromise, civility, and cooperation in politics; however, it seems we demand that compromise come strictly from our political opponents. Oddly, lamenting partisan division is itself an expression of our animosity towards the other side. That is, the distance we see between ourselves and our political others is perceived as their distance from our ideas, their resistance and recalcitrance to our thoughts. Consequently, even though Republican and Democratic citizens generally are no more divided over central public policy issues than they were forty years ago, we are more partisan than ever in that we are more inclined to regard our partisan opponents as untrustworthy, dishonest, unpatriotic, and threatening.

In other words, partisan division is a matter of our negative feelings towards the other side, rather than disagreements over political ideas. Perhaps unsurprisingly, citizens’ political behavior – voting, donating, volunteering, and so on – is now more driven by animosity for the opposing party than by commitment to the ideals of our own.

This animosity is tied to a range of phenomena which have rendered our partisan identities central to our overall self-understandings. In the United States, liberalism and conservatism are distinct lifestyles, with partisan identity serving as the “hyper-identity” that organizes all of the other aspects of our lives, from our consumption habits to our religious affiliations and views about family and child-rearing. As we grow to see our partisan rivals as living strange lives that differ from our own, we come eventually to see their lives as alien and eventually degenerate. Seeing them in this way, we project on to them exaggerated vices, including close-mindedness, untrustworthiness, lack of patriotism, dishonesty, and general immortality. From there, we then infer a vast divide over democracy itself, with no common ground or basis for cooperation. What is shared government with those who appear to be moral aliens?

Biden’s recipe for political healing is thus fraught. Read more »

by Jonathan Kujawa

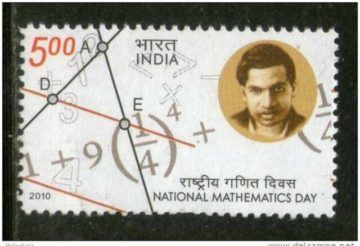

On December 22nd I started thinking about topics for this month’s 3QD essay. In a happy coincidence, someone posted to Twitter that Srinivasa Ramanujan was born on December 22, 1887. We’ve touched on Ramanujan’s work here at 3QD, but it seemed like a sign that we should dive a little deeper [0].

The story of Ramanujan is now famous, especially after the award-winning film “The Man Who Knew Infinity” [1]. He was born in southern India into a poor family. His talent in mathematics was noticed at an early age, but it wasn’t until he got hold of a copy of G. S. Carr’s “Synopsis of Pure and Applied Mathematics” at the age of fifteen that his talent was really revealed. Carr’s book was meant to be a Cliff Notes to undergraduate mathematics for students cramming for Cambridge University exams. It gave little to no explanations — just a thousand pages of raw, uncut mathematical formulae stated as gospel. Using Carr’s book, Ramanujan taught himself mathematics.

Ramanujan became consumed with his own mathematical explorations. So much so that he neglected his college studies and failed out after the first year. He continued to do math and live in poverty until his mother arranged for him to marry S. Janaki in 1909. Feeling the responsibility of marriage, Ramanujan eventually found employment as a clerk in the Madras Port Trust Office and in 1913, thanks to the encouragement of other mathematicians in India, finally sent a letter containing some of his results to several famous mathematicians in the UK.

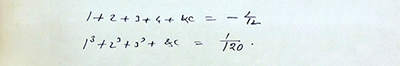

Faithful 3QD readers might recognize the first of the following formulas from Ramanujan’s letter:

In one of my first essays for 3QD I talked about how you can make sense of infinite sums and how, properly interpreted, it is reasonable to think of the sum of all the counting numbers as equal to -1/12. Read more »

by David Kordahl

Last month I worked on a modern sort of archaeological dig, going through the equipment in a college physics lab to see what sorts of devices were on hand. It reminded me of being a little kid, when I would tiptoe around my dad’s religious paraphernalia (he was a Lutheran pastor), not really knowing what everything was for, but being sure that each item had a definite purpose. My job in the lab was to construct setups for a modern physics course, demos for students to learn a few things about the empirical basis of special relativity and quantum theory, to cut through the layers of interpretative bullshit. Encountering unfamiliar items, I would rummage around for their service manuals, pushing aside brittle O-rings and chipped pipettes, stacking old printouts, believing without proof that the lab’s former occupants had found some use for these treasures.

In bed one night after a long day with the machines, it occurred to me that these educational toys might share some common purpose with the portable communion kits and illustrated Bibles of my childhood. In each case, the devices were technologies designed to strengthen belief in a distinct mask for the world of observed phenomena. And in each case, strengthened beliefs hold for believers the promise of new ways to navigate the world, ways that non-believers can neither appreciate nor access.

This is not to deny the obvious differences between a communion kit and a current amplifier. One obvious feature of technology is that it’s mostly belief-proof. Almost no one understands all the devices that they use, and many users hold views that explicitly contradict the theories used to construct the devices on which they rely. (Teaching high school science, I met smartphone savants who were supremely confident in the irrelevance of physics to their lives.) Yet the fact that I now entertained the possibility that my lab setups had anything to do with religious conversion already proved that I’d strayed pretty far from my early days. Read more »

by Tim Sommers

The Medieval Arabic philosopher Ibn Sina – Avicenna to Europeans – was rivaled in renown as a thinker in the Islamic world only by Al Farabi and hailed as “the leading eminent scholar” (ash-Shaykh ar-Ra¯sı ) of Islam. He worked in virtually every area of philosophy and science and influenced subsequent Jewish and Christian philosophers almost as much as Muslim ones. But he is probably known best for a single image, a heuristic more than a thought-experiment, “the falling person”.

“We say: The one among us must imagine himself as though he is created all at once and created perfect, but that his sight has been veiled from observing external things, and that he is created falling in the air or the void in a manner where he would not encounter air resistance, requiring him to feel, and that his limbs are separated from each other so that they neither meet nor touch. He must then reflect as to whether he will affirm the existence of his self. He will not doubt his affirming his self-existing, but with this he will not affirm any limb from among his organs, no internal organ, whether heart or brain, and no external thing. Rather, he would be affirming his self without affirming for it length, breadth and depth. And if in this state he were able to imagine a hand or some other organ, he would not imagine it as part of his self or a condition for its existence.”

Ibn Sina’s ultimate aim was to prove the existence of the soul. Let’s leave that more complicated task aside and stick to the question of what “the falling person” might tell us just about the existence of a self.

Ibn Sina, by all accounts, didn’t count “the falling person” as proof of the reality of the soul or self. He taught his students a whole chain of sophisticated arguments for that purpose. He described “the falling person” more as “alerting” or “reminding” us of the self. It’s not quite a thought-experiment. It’s not about how you would react. It’s not a puzzle with a solution. It’s a question. And the question is, if you were without a past and shut off from any input external or internal, would you have or be a self? Or, maybe, would a self still be there? Would you, could you, think, I am here? Or I am me. Or I am something.

What would this bare self’s awareness of its self be like?

I picture a hum.

Just to the right of where I sit now there’s a freezer on the other side of a closed door. But I can still hear the hum. It only comes into my awareness when there’s dead silence and my mind goes blank for a moment. But it’s always there. The kind of self that “the falling person” might have, I picture as that hum. No content just…there. But is it really there? Couldn’t the falling man think? Read more »

by Thomas Larson

It’s Monday, 1:45, and six men and I sit in a circle with our German-trained psychotherapist, an imperious woman who reminds us that she is here to help only if we get bogged down or offer guidance and that we men need to find our own way through our turmoil, which is the point of the group and the point of each of us paying $3000 per year. I’m fairly new, so before I speak, I’m seeking some level of comfort or commonality among us, and every week I come up short. I’m not yet adjusted and unsure what I should be adjusting to.

It’s Monday, 1:45, and six men and I sit in a circle with our German-trained psychotherapist, an imperious woman who reminds us that she is here to help only if we get bogged down or offer guidance and that we men need to find our own way through our turmoil, which is the point of the group and the point of each of us paying $3000 per year. I’m fairly new, so before I speak, I’m seeking some level of comfort or commonality among us, and every week I come up short. I’m not yet adjusted and unsure what I should be adjusting to.

Obviously, I don’t know these men. And I doubt I’d associate with them outside this forum or be in a social situation where we’d meet. Case in point, the tanned man (our real names cannot be shared). The tanned man has the time-clocked sadness my father had at fifty-five, the greying hair above his ears, the loyalty to a global corporation and the ease of leveraged investments about him, a man who regards his goldenness as some golf-cart anhedonia, with his deck shoes, and his velour pullover, and his browning legs and white ankles and baggy, bluish shorts, and his marriage run aground, whose chassis has been scraping the gravel for a couple years now.

He says everything he’s tried won’t move the needle, that is, between him and his wife. The strangely placid woe he wears into our sessions I find disturbing; he always sits in the room’s lone hard back chair, best, he says, for his sofa-ruined back, telling us, as he did last Monday, that he’s still sleeping on the leather couch in the basement where she sentenced him (hard-on in tow, an adolescent bit of humor) and where nailed above the foot of the stairs a little plaque reads, I’m not kidding, “Man Cave.”

His tortured spine is no better, he says, even after a beach-walk and the treadmill, and yet he seems relaxed becoming, I presume, accustomed to us commiserating with his fraught condition, we his brethren therapists, though there’s wariness and worry in how often his legs cross and uncross as if this is a job interview: Why do I notice all this? Why can’t I concentrate on my own shit? I’ve got plenty of it, guy-wired in me and my partner, a problem with medications. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by David Oates

We are entering the aftermath. Two of the most epic and wrenching struggles in American history are finally playing out to their conclusions. At last we see a conclusive democratic rejection of a presidency built on systematic lying and racism. At the same time we look just weeks or months ahead for vaccines that will liberate us from our deadly yearlong pandemic.

We are entering the aftermath. Two of the most epic and wrenching struggles in American history are finally playing out to their conclusions. At last we see a conclusive democratic rejection of a presidency built on systematic lying and racism. At the same time we look just weeks or months ahead for vaccines that will liberate us from our deadly yearlong pandemic.

Of course the two catastrophes are entwined, most wrenchingly in the excess numbers of Americans who died not just because of the disease, but by the incompetence and malfeasance of the president’s handling of it. According to a summary by the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (October 2020), “If the coronavirus death rate in the United States were similar to that of Australia, it would have had 187,661 fewer COVID-19 deaths . . . and, compared with Canada, it would have had 117,622 fewer deaths.” And another hundred thousand US deaths have accumulated since October. So amplify those numbers accordingly, please, as this president’s personal death-toll on the nation.

Our collective house in disorder, occupied by thugs and dying by the thousands. All coming, at last, to an end! An end to constant alarm and worry. An end to the adrenaline-rush of hyperalertness, the daily fight-or-flight. The four-year emergency. The cavalcade of death. The pageant of ignorance.

Who are we now? we might soon be asking ourselves, as we step out, one by one, from our psychological foxholes and almost-literal bunkers. Can we relax now? Can we pick up normal life again?

Can we? Will we?

The after-blight is beginning. How shall we then live, in the aftermath of so much sustained stress and fear and misery? Read more »

by Chris Horner

A Task for the Left

A Task for the Left

‘Freedom’ must be about the most popular term in the world of politics, and not only in that world. But what does it actually mean, in social and political terms? How should people who want to be broadly progressive understand it? Too often the Left finds it hard to articulate just how they stand in relation to it and the effect is to cede the term to the Right. This is important, as the word, vague as it is, carries enormous affective force. It matters to people, because it represents a vital human aspiration. And so it’s too important to be abandoned to the people who are, for all their rhetoric, actually the enemies of freedom. On their account of it, freedom is just about individuals having more choices. This is a very weak account of freedom that ought to be met head on and refuted. It won’t do to change the subject, or talk vaguely about equality and solidarity: the Left needs make it clear what freedom is, what it isn’t, and what it could be. If it doesn’t, it risks being portrayed as being ‘against’ freedom, and in favour of mediocre uniformity and regimentation. So we end up with two caricatures, one about freedom and the other about its supposed enemies.

2020 had plenty of examples of this weak version of ‘freedom’. The Covid pandemic led to masks being rejected, vaccines shunned and lockdowns attacked and breached, all in the name of individuals’ rights and freedoms and ‘freedom of choice’. Beyond Covid, in the UK the freedom flag has been waved in support of Brexit, which apparently also means freedom, via the sloughing off of regulations. In the UK and US the word is hardly ever out of the mouths of Prime Ministers and Presidents. Hardy perennials of the right continue to be diatribes against against Health and Safety at work (‘red tape’), tax (the freedom to spend the money one earns as one pleases) and of course, in favour of arrangements that allow ‘flexible working’ – supposedly to free up the choices of employer and employee, but which in fact confirm the precarious status of hundreds of thousands of workers. Then there are ‘free schools’, free markets and much more. It’s an extremely long list. The Left is generally cast as the enemy of all this, the enemy of aspiration, of social mobility, of the opportunity to become a billionaire. It just wants equality, which stifles freedom.

How should one respond to this? Read more »

by Varun Gauri

The spirit of gift exchange animates democracy. In exchange for letting you control government, giving you power over the security forces, the common treasure, and the agencies and civil service — which is power over me — you agree to grant me those same powers — and power over you — in the future. I am then entitled to control government and its coercive powers in exchange for agreeing to transfer those powers back to you, or your representatives, when the time comes.

Aristotle emphasized this, arguing that in political regimes where citizens are more or less equal, the citizens alternate governing, “ruling and being ruled in turn.” Rawls believed this notion of reciprocity in democratic societies is widely relevant across a range of social and economic practices, including taxation: Because society should be seen “as a fair system of cooperation over time,” not only public offices but the common surplus should be divided in a way that acknowledges mutual contributions over time. My firm profited from those highways and airports and bridges that others paid for and built; now I pay it forward, in the form of taxes.

This principle of reciprocity applies not only to taxation and to ceding control of government — conceding after an election loss — but to forbearance in the exercise of power. When I’m in power, the principle requires me to appreciate that the security forces, the common treasure, and the civil service are not mine to control forever. One day they will be yours. So I shouldn’t break or repurpose them in a way that leaves them not useful to you, for your objectives, when it becomes your turn to rule. It’s hard to specify the point at which the pursuit of ordinary policy objectives amounts to breaking or repurposing institutions and agencies, but the line certainly exists. An outgoing administration repurposing the civil service by installing loyalists, or by raiding the treasure, is, after a certain point, normatively equivalent to an executive embezzling funds from a business partner (or worse). Read more »

by Brooks Riley

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon.

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon.

Where did this come from, this semi-androgenous role so foreign to my timid female self? I may have been feeling powerless back then, on the verge of puberty and alone in my ignorance. My daydream could just as easily have come from a twelve-year-old boy but more likely it incubated in the tomboy I sometimes was. Gender had little to do with it, though. Empowerment is what mattered, something I desperately needed, as well as a jolly exciting way to pass the time until I fell asleep.

Daydreams have served the needs of human beings since the evolution of the imagination a few million years ago. The caveman who dreamed of bagging a boar pictured an encounter in his mind and practiced his moves. Except for those with aphantasia, we can all visualize places we’ve been and people we’ve seen. This ‘inner eye’ allows us to do much more than that—to create people and places that we’ve never seen, that don’t exist, and to give them life, context, and raisons d’être. This is how fiction is born, before the first word has even hit the page.

We all indulge in daydreams, those reticules in the mind that hold our most vivid hopes in the form of mise-en-scène, endowing our bucket list with emotional nuance and narrative—however improbable the reality. With age, however, imagining a dazzling future no longer seems viable, as the scope of our hopes and desires shrink, like the law of diminishing returns. Daydreaming is eventually reduced to hardly more than an imagined walk in the park when you’re stuck at home. Much of my bucket list has been accomplished, in sometimes surprising ways. My life has been eclectic, peripatetic, unexpected, and gratifying. I’ve been places, done things. What more could there be to dream about? Read more »

by Hari Balasubramanian

This year marks two decades since I moved from India to the United States. I look back at how it all began in Arizona.

In the summer of 2000, after completing my bachelor’s degree in engineering, I had to decide where to go next. I could either take up a job offer at a motorcycle manufacturing plant in south India, or I could, like many of my college friends, head to a university in the United States. Most of my friends had assistantships and tuition waivers. I had been admitted to a couple of state universities but did not have any financial support. Out a feeling that if I stayed back in India, I’d be ‘left behind’ – whatever that meant: it was only a trick of the mind, left unexamined – I took a risk, and decided to try graduate school at Arizona State University. I hoped that funding would work out somehow.

In the summer of 2000, after completing my bachelor’s degree in engineering, I had to decide where to go next. I could either take up a job offer at a motorcycle manufacturing plant in south India, or I could, like many of my college friends, head to a university in the United States. Most of my friends had assistantships and tuition waivers. I had been admitted to a couple of state universities but did not have any financial support. Out a feeling that if I stayed back in India, I’d be ‘left behind’ – whatever that meant: it was only a trick of the mind, left unexamined – I took a risk, and decided to try graduate school at Arizona State University. I hoped that funding would work out somehow.

So in August 2000, I found myself traveling across continents to this powerful country that I knew little about. It was my first ever time outside India and my first ever flight. From Chennai, I flew to Kuala Lumpur, then, after an eight-hour layover which I didn’t mind at all, to Los Angeles and finally, after the worry of a missed connection, to Phoenix, Arizona. The gleaming, modern airports, the meals and the movies, the turbulence and the clouds: it was all very exciting, a glimpse of an elite world that had once seemed inaccessible.

At the Phoenix airport, someone from the Indian Students Association at ASU came to pick me up. After what seemed like a recklessly fast drive – in fact it was normal: it’s just that I’d never experienced a 70-miles-an-hour ride on a highway before – he dropped me off at an apartment shared by three Indian grad students. One of them, my host until I found an apartment, wore a veshti, the wraparound skirt common in south India. He spoke Tamil fluently; he spoke it so well that I could well have been in my home state. I had a nagging suspicion at the time that people might change as soon as they landed in a foreign country – that they might change their attire, even forget their mother tongue. It was reassuring to know that wasn’t true. At the heart of such doubts, I see now, was a fear that I would quickly surrender my Indianness. Read more »

by Ali Minai

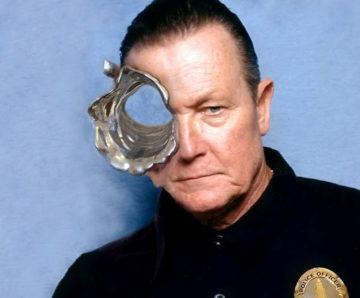

One of the most interesting and memorable characters in sci-fi films is the T-1000, the shape-shifting, nearly indestructible robot from the classic film Terminator 2: Judgment Day, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. There are other, less prominent examples of shape-shifting intelligent beings in sci-fi – for example Odo, the chief of security on Star Trek’s Deep Space Nine, or the electromagnetic, gaseous, and otherwise inchoate life-forms encountered in various Star Trek episodes. These fictional examples raise the interesting question of whether intelligent beings without a fixed structure are feasible in practice – naturally or through technology (In fact – speaking of Star Trek – the question could potentially be extended to teleportation as well since that would presumably involve the re-assembly of a disassembled body, but that is too remote a possibility to consider for now.)

One of the most interesting and memorable characters in sci-fi films is the T-1000, the shape-shifting, nearly indestructible robot from the classic film Terminator 2: Judgment Day, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. There are other, less prominent examples of shape-shifting intelligent beings in sci-fi – for example Odo, the chief of security on Star Trek’s Deep Space Nine, or the electromagnetic, gaseous, and otherwise inchoate life-forms encountered in various Star Trek episodes. These fictional examples raise the interesting question of whether intelligent beings without a fixed structure are feasible in practice – naturally or through technology (In fact – speaking of Star Trek – the question could potentially be extended to teleportation as well since that would presumably involve the re-assembly of a disassembled body, but that is too remote a possibility to consider for now.)

Recently, several research groups have worked on building robots that can reconfigure themselves autonomously into different shapes and perform different types of actions suitable to their current form. For example, a robot consisting of a large group of small, identical modules could turn itself into a compact sphere to roll down smooth surfaces, flatten itself to slide under doors, grow limbs to climb stairs, or take a snake-like form to crawl away. Such robots, with various degrees of reconfigurability, have now been implemented extensively, both in simulation and in actuality. Some of these robots are, in fact, controlled by external computers to which they are connected or by a centralized brain built into the robot, but the more interesting ones are based on distributed autonomous control: Each module in the robot communicates with other modules near it and, based on the information obtained, triggers one of several simple programs it is pre-loaded with. These programs might cause the module to send out a particular signal to its neighbor or make a simple move such as a rotation, alignment, detachment, or attachment. As all these mechanically connected modules signal and move in response to their triggered programs, the robot assumes different shapes and global behaviors such as locomotion or climbing emerge through self-organized coordination.

The primary feature in these robots is what might be termed radical reconfigurability, i.e., no elementary component has a fixed location in the body or is specialized to a task; like Lego pieces, it can serve any role anywhere. However, this property depends on another, more general attribute: radical distributedness. A radically distributed system consists of identical and exchangeable modules with no permanent functional specialization: Any module can take on any role as needed. Read more »