by John Schwenkler

This is the third in a series of posts discussing different ways of pursuing philosophical understanding. The first two parts can be found here and here.

Several years ago I taught an undergraduate course that I gave the unfortunately profound-sounding title “Know Thyself: A Philosophical Investigation of Self-Knowledge”. In it, we mainly read a range of texts that explored in different ways the topics of self-knowledge and self-discovery, illuminating the way that it can be an achievement to know oneself in the face of the manifold barriers to doing this.

What made this course different from the ones I was used to teaching was that our readings were drawn principally from literary fiction and non-fiction rather than traditional philosophical writings. It was, however, entirely in keeping with the sort of teaching I was accustomed to in that the overarching focus of the course was entirely theoretical—a fact that came to my attention when one of my students observed that she’d expected that the course would have something to do with the practical task of achieving self-knowledge, rather than the abstract question of what self-knowledge is. When I heard this question, I laughed inside—what a bizarre idea, and indeed a dangerous one, to try in a philosophy course to figure out who one is!

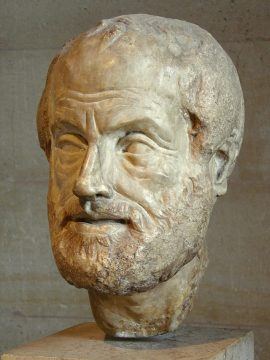

But of course it was my position, not hers, that counts as the bizarre one if one considers the nature of philosophy against the background of its history. Socrates, for example, took up general questions about the nature of knowledge, justice, piety, and so on as part of a life that aimed at improving the lives of his fellow Athenians. Aristotle began his Nicomachean Ethics with the remark that a philosopher should come to ethical theorizing “not in order to know what virtue is, but in order to become good, since otherwise our inquiry would have been of no use”. René Descartes summed up his philosophical project in a short work titled The Discourse on Method, which describes a moral and intellectual code that he undertook to follow in order to use his reason rightly. And so on. For these philosophers, the idea that philosophy was an abstract discipline that could be approached without an eye toward real-life consequences would have been truly unfathomable. It’s only in the context of the modern university, where philosophy is conceived alongside mathematics, biology, psychology, and so on as one among many academic subjects, that self-knowledge could be seen as a philosopher’s subject-matter rather than her essential task.

**

I am mindful of these questions today thanks to having just finished reading the philosopher Nathan Ballantyne’s new book Knowing Our Limits, which begins with some similar observations about the state of contemporary epistemology. As Ballantyne explains, since the 1960s the overwhelming focus of Anglophone philosophers writing about the nature of knowledge has been in proposing and considering various candidate analyses of knowledge and other related concepts. This project took its bearing from Edmund Gettier’s classic paper “Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?”, which presented several counterexamples to the thesis that having a belief that is both justified and true is sufficient for that belief to be an instance of knowledge. Ballantyne describes the professional situation that Gettier’s famous argument brought into being:

The goal was to describe epistemological concepts. Eventually, there were many new descriptive projects afoot and the popularity of these projects meant that professional training and incentives shunted fledgling scholars toward still more research describing epistemological statuses and principles. Graduate students were trained in the techniques of analysis and counterexample. Students gunning for careers in research could easily see the recipe for success: refute theories published in issues of Analysis or The Journal of Philosophy, do even better in the game of analysis, or analyze something else that makes a splash. Over the decades, descriptive theorizing became the field’s dominant approach, passed on through new forms of training, conceptual tools, and professional enticements.

In some ways this state of affairs has been good for professional philosophers: it has yielded some real intellectual fruits, and given us a way of doing research that more closely resembles the methods of natural science, thus helping to justify our existence in the eyes of university administrators and funding bodies whose focus is on concrete research outputs. But Ballantyne observes its downsides:

Crucially, success in the business of epistemological description doesn’t require much familiarity with actual human inquiry. As the philosophical study of knowledge grew up, it had very little to do with knowledge-seeking. … The field’s inertia has led most epistemologists to practice a kind of epistemology that has little to do with guiding inquiry.

There are several points at issue here. One is the detachment of philosophical theorizing from anything specifically human about human inquiry: as a rule, the analyses of the concept of knowledge that are considered by philosophers could all apply equally well to angels or aliens, and so the philosopher’s task can proceed without any detailed knowledge of human nature. But the point that is more important to Ballantyne is that most philosophers make little if any attempt to theorize in a way that could guide actual human inquirers toward a better use of our cognitive powers. The point of doing epistemology isn’t to help us to achieve knowledge, except in relation to abstract questions like what the proper definition of knowledge is.

**

In addition to revealing the strangeness of this conception of philosophy by contrasting it with the much more practically oriented approach of great philosophers like Descartes, John Locke, and Francis Bacon, Ballantyne also proposes a different approach to epistemological theorizing that takes its inspiration from the work of those greats. The aim of Knowing Our Limits is to describe, and begin to work out the details of, a regulative epistemology whose aim is not to describe what knowledge is, but to make people into better thinkers who are more aware of their cognitive limitations. Here is how Ballantyne sums the project up:

Regulative epistemology’s broad-based research program is prompted by a concrete problem: our intellectual imperfections. The problem is an old one, but regulative epistemology aims to attack it in a special way. Three perspectives normally disconnected must be joined together: descriptive, normative, and practical. Corresponding to each perspective is a general question. What are inquirers like? What should inquirers do? How can inquirers do more of what they should? The research program involves describing inquirers, understanding what they should do, and figuring out how they can better reach their epistemic goals.

As I have indicated, it’s essential to Ballantyne’s regulative project that the inquirers he’s concerned with are human inquirers, and that the description of what these inquirers are like take its bearing from what we know of human nature. Ballantyne argues that this demands attention to what psychologists and cognitive scientists have discovered about the various forms of bias and unreasonability that make us prone to put too much trust in our own thinking and fail to respond appropriately to the controversial status of many of our deeply held beliefs. Recognizing these facts about ourselves should lead us to decrease our confidence in many of these beliefs and take a more tolerant and open-minded attitude toward those who disagree with them.

Another of the most interesting elements of Ballantyne’s book is his discussion of what might make it possible for the principles framed by a regulative epistemologist actually to do any real work in guiding the way a person thinks. He situates this discussion in the context of the distinction drawn by many psychologists between two “systems” that work to shape our judgments. One of these systems is fast, automatic, and unconscious, generating the “snap” judgments that facilitate quick recognition and unreflective decision-making. The other is slow, deliberate, and conscious, requiring us to “stop and think” before making up our minds about how things are. Given how much of our thinking is unreflective and outside the reach of consciousness, what is hope is there that philosophical principles could make a difference to it?

Ballantyne’s answer is promising. He argues that what’s needed for a philosophical framework to make a difference to actual human inquiry is that the framework be mirrored in what he calls a picture that can come easily to mind and make a difference to our subsequent thinking. And his task in Knowing Our Limits is to give us such a picture of ourselves and our cognitive limitations, in order that we might take this picture to heart and thereby come to reason better.

**

As I have indicated, it is not just in the subfield of epistemology that the pressures of professionalization have led philosophers to do our work in a way that is largely detached from the aim of guiding human life. That observation applies equally well to a great deal of the work that goes on even in areas like moral and political philosophy, where the potential for practical relevance is most obvious, yet the majority of what philosophers think about has only a tenuous connection to real-life concerns, and our writings say practically nothing about how people should actually live. While all this helps philosophers to have a closer resemblance to scientists in the way we conceive of our research and measure its outputs, ultimately the value of those outputs is found in the importance of the questions they help us to answer. And it seems clear that the question “How can we be better?” deserves to be included pretty prominently among these.

But while that much is obvious, the challenge it poses to a professional philosopher like myself is frankly immense. Even if I could get beyond that initial response to the question from my undergraduate student, I’d find myself with nearly nothing to say about the practical task that was her interest. Achieving self-knowledge? That does seem like something philosophy should be able to help with. (Indeed, I could easily write a short essay explaining why that is so.) But how would I go about this? At this point my ideas run dry, my professional training not having required much familiarity with actual human beings. This might have to wait until next semester.