by Philip Graham

I’ve long been partial to Portuguese culture, so when Portugal transferred its last colonial holding, Macau, back to Chinese rule in 1999 , a friend surprised me with his marveling reaction: “Portugal had an empire? Who knew?”

I’ve long been partial to Portuguese culture, so when Portugal transferred its last colonial holding, Macau, back to Chinese rule in 1999 , a friend surprised me with his marveling reaction: “Portugal had an empire? Who knew?”

Perhaps his reaction shouldn’t have surprised me. In the United States, steeped as we are in the history of the United Kingdom’s “empire on which the sun never sets,” few are aware that the Portuguese accomplished the first European globe-spanning empire, beginning in the 15th century.

When I lived in Lisbon for a year, I noticed that my Portuguese friends wrestled with the legacy of their country’s history. They felt pride at the achievements of their intrepid ancestors’ global reach. But they also felt shame, because while all empires break too much before they reshape the chaos they created, Portugal’s empire was especially bad.

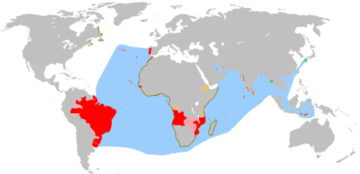

The Portuguese initiated the transatlantic slave trade in 1444, which has bedeviled and tormented much of the world ever since. Sixty years later, the Viceroy Alfonso Albuquerque expanded Portuguese power not only as exploration for economic reasons, but as a brutal crusade against Islam. By 1580, the empire extended from Brazil to Africa, from India to Malaysia and on to the Indonesian island of Timor.

The Portuguese initiated the transatlantic slave trade in 1444, which has bedeviled and tormented much of the world ever since. Sixty years later, the Viceroy Alfonso Albuquerque expanded Portuguese power not only as exploration for economic reasons, but as a brutal crusade against Islam. By 1580, the empire extended from Brazil to Africa, from India to Malaysia and on to the Indonesian island of Timor.

So what happened to this Portuguese empire, which now no longer exists? Read more »

White Americans get a lot of things wrong about race. And not just the relatively small number of blatant white supremacists, or the many millions (

White Americans get a lot of things wrong about race. And not just the relatively small number of blatant white supremacists, or the many millions (

Not long ago, a reader complained, politely but firmly, about your humble author’s regrettable tendency to post something called “Blah blah blah pt. 1” and then never get back to it for part two, in particular the post about history, wondering if possibly I thought no one would notice that I had left it hanging. I admit the fault, but I assure my patient reader, or possibly readers, that I do indeed intend to finish each and every one of my multipart posts, and even to make clear how they are related to each other. (That’s the intent, anyway.) So fear not! (I do have to read some more history though … !) This time, though, I finish a different sort of multipart post: my end-of-2020 podcast. Plenty of unfamiliar names, even to me, but some great stuff! As always, widget and/or link below.

Not long ago, a reader complained, politely but firmly, about your humble author’s regrettable tendency to post something called “Blah blah blah pt. 1” and then never get back to it for part two, in particular the post about history, wondering if possibly I thought no one would notice that I had left it hanging. I admit the fault, but I assure my patient reader, or possibly readers, that I do indeed intend to finish each and every one of my multipart posts, and even to make clear how they are related to each other. (That’s the intent, anyway.) So fear not! (I do have to read some more history though … !) This time, though, I finish a different sort of multipart post: my end-of-2020 podcast. Plenty of unfamiliar names, even to me, but some great stuff! As always, widget and/or link below. Do you have a right to own a microwave oven? To be clear, ideally in a free society, absent a clear showing of harm to others, there’s a presumption that you can do whatever you want and own whatever you can make or buy. So, you do have a basic right to own things – to acquire property, as political philosophers like to say. But it’s consistent with that right for there to be a lot of rules and regulations around what you can own – and even prohibitions on owning certain kinds of things.

Do you have a right to own a microwave oven? To be clear, ideally in a free society, absent a clear showing of harm to others, there’s a presumption that you can do whatever you want and own whatever you can make or buy. So, you do have a basic right to own things – to acquire property, as political philosophers like to say. But it’s consistent with that right for there to be a lot of rules and regulations around what you can own – and even prohibitions on owning certain kinds of things.

For those of us who classify ourselves as Nones—

For those of us who classify ourselves as Nones—

The presence of covid-19 running amok amongst us has momentarily disrupted the perimeters of our lives. That two, three, or possibly four generations are not always able to gather together under one roof has given rise to greater appreciation of the family.

The presence of covid-19 running amok amongst us has momentarily disrupted the perimeters of our lives. That two, three, or possibly four generations are not always able to gather together under one roof has given rise to greater appreciation of the family.

1. “A more perfect union.” The Founders expressed a breezy confidence, didn’t they? As if such a thing were possible – the distant states cohered into a nation; the various occupants working it all out. Loyal. Collaborative. Taking part in the common welfare. While remaining, of course, individual and autonomous and free, free, free. (Certain restrictions applied.)

1. “A more perfect union.” The Founders expressed a breezy confidence, didn’t they? As if such a thing were possible – the distant states cohered into a nation; the various occupants working it all out. Loyal. Collaborative. Taking part in the common welfare. While remaining, of course, individual and autonomous and free, free, free. (Certain restrictions applied.)