by Michael Liss

The rights and interests of the laboring man will be protected and cared for, not by the labor agitators, but by the Christian men to whom God in His infinite wisdom has given control of the property interests of the country, and upon the successful Management of which so much depends. —George Baer, President of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, during the Coal Strike of 1902.

Whenever I read yet another article about intramural warfare in the Democratic Party over which candidate will be progressive enough for the Progressive wing, I think about that quote.

Know your enemy, know yourself. Do contemporary Progressive politicians really know either? The “old” Progressivism, which reached its zenith in the period between 1896 to 1916, was primarily a social and political reform movement. Faced with the excesses of the unbridled capitalism of the Gilded Age that had preceded it, it did not look first toward redistribution. Rather, it took aim at the pervasive rot that was created as immense wealth was being made in businesses like mining, railroads, shipping, steel, meatpacking, and finance, often at the expense of the working man, the farmer, and the small businessman. From this, it drew its moral force.

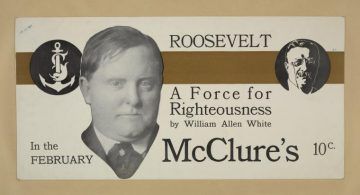

We should acknowledge that those fortunes were the product of the efforts of real visionaries, larger-than-life figures like Vanderbilt, Jay Gould, James J. Hill, the Armour and Swift families, J.P. Morgan, Rockefeller, and Carnegie. Talent aside, though, their successes were enhanced by the sharpest, most predatory tactics, of the type described in Ida Tarbell’s The History of The Standard Oil Company, a 19 part series in McClure’s Magazine, which chronicled the rise of Standard Oil. Business was not for the faint of heart, and the most successful businessmen were monopolists who went from strength to strength, squeezing every competitor, and every last dollar, out of every transaction.

No matter how entrepreneurial the businessman, no matter how rich the oilfield, no matter how coldly efficient the operator, it couldn’t have been done without grease. Corruption was literally everywhere.

State and big-city government often amounted to organized thievery, with bribery and favoritism at every level. Licenses, jobs, concessions and contracts, franchises for the operation of electric street railways, telegraph and telephone lines—everything had a price. The cash reached as high as the federal court system and Congress, with Senators just as prone to having a hand out as local aldermen. And why shouldn’t they? Before the 17th Amendment, Senators were selected by State legislators, and not answerable to the public in a direct election.

There was also a philosophical undercurrent, perhaps too bluntly expressed by George Baer, but shared by many of his caste: a strong sense of Social Darwinism, a belief that good fortune was reflective of a natural superiority and effort, and bad fortune of laziness and immorality. With that as their “reality,” it was thought that government should stay out of the relationships between capital on the one hand, and labor and consumers on the other. If there were to be any government intervention, it should simply be to afford police protection to those men of property.

Just as this philosophy influenced the treatment of gigantic industries, so too did it affect more niche markets, like the one for Patent Medicines. The same forces applied, and the argument we sometimes hear now in opposition to regulation—that the market will self-regulate—was shown to be true in reverse. Those who wanted to play it straight found themselves at an enormous competitive disadvantage. Better to sell something worthless and even dangerous than not to sell anything at all.

Just as this philosophy influenced the treatment of gigantic industries, so too did it affect more niche markets, like the one for Patent Medicines. The same forces applied, and the argument we sometimes hear now in opposition to regulation—that the market will self-regulate—was shown to be true in reverse. Those who wanted to play it straight found themselves at an enormous competitive disadvantage. Better to sell something worthless and even dangerous than not to sell anything at all.

Demographics and geography also played roles in creating demand. In 1900, 60 percent of the population lived in rural areas, about two thirds of that on farms. Doctors were not always available, and did not always have either the best training or equipment at hand. Not everyone made the connection that Lister and Pasteur did in the 1850s and 60s, between dirt and infection. As they often lacked adequate anesthetics and were unable to control blood loss, surgeons operated quickly, so nuance was out, making recovery longer and more painful. When they did cut, they did so with bare and sometimes unwashed hands and unsterilized equipment. Not surprisingly, mortality rates were exceptionally high. As to the cities, pockets of wealth supported patrician doctors, but elsewhere, especially in areas that drew large numbers of immigrants, often unspeakable squalor prevailed.

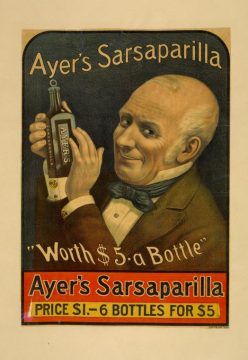

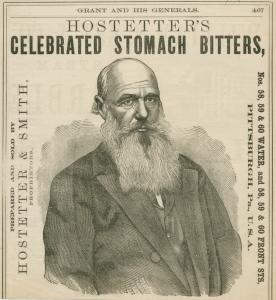

As for even common diseases, running the spectrum of what we would now consider minor to life-threatening, there were no antibiotics, no insulin, and very little in the conventional formulary to cure what ailed people. There was also a strong tradition among rural and immigrant families of self-reliance and the use of home-brewed remedies. Patent Medicines, often packaged and marketed in interesting ways, reasonably priced at perhaps $1 a bottle for multiple doses, and supposedly containing miracle ingredients, were a lot more convenient and cheaper than calling for a doctor. We’ve all seen the prototypical snake-oil salesman in movies like The Outlaw Josey Wales and Little Big Man, but this wasn’t all hucksters in sharp suits. Sears Roebuck, in its 1892 catalog, devoted more than 30 pages to a variety of pills, elixirs, ointments, and devices.

What did they cure? The better question is, what did they claim to cure? Cancer, Coughs, Consumption, and the dreaded Catarrh. Paralysis and Pleurisy. Tremors, Chills, and Fevers. Rheumatism, pimples, spinal issues, eye sores, ringworm, and dyspepsia. Every claim was served up with a little flair from the emerging world of advertising.

What wonderful names and commanding slogans those ads offered: “Dr. William’s Pink Pills for Pale People,” which claimed to have saved a boy from paralysis, and “Dr. Fenner’s Cough and Cold Syrup,” which even promised to be free of opium, morphine, or any narcotic. “Dr. Ayre’s Cherry Pectoral,” which would cease your cough, strengthen your throat, and heal your lungs. “Kemp’s Balsam,” which urged you not to delay, because it was a “sure cure for Consumption in the early stages,” and was also effective on Whooping Cough and Influenza. If all else failed on the respiratory front, “Smith’s Throat And Lung Balm” was no less than “Nature’s Invincible Panacea.”

Ah, Nature. Cure or kill, so let’s not leave out what nature could have in store. The terrifying tapeworm was one of the scourges of the age, often transmitted through undercooked food or the unwashed hands of unsanitary food preparers (of which there was an abundance). There are, apparently, several varieties of these colorful parasites, going by a variety of intimidating names, like T. saginata, T. solium and T. asiatica. Tapeworms head to the intestinal tract, hang out, feed, and decide to reproduce (in enormous numbers). They also occasionally grow far too large for comfort (or health), and migrate to more unfortunate places in the body. In case you needed a little extra push, in the advertising of the time, tapeworms looked much like Amazonian Anacondas. But, fear not. “Kemp’s Vegetable Pastilles” was ready, and “The Kickapoo Indians Tape-Worm Secret” was “sure to get the head, body and all.”

So many organs, so many opportunities. The Liver was a big one. While the French were supposedly experts in livers, if you had to buy domestic, there was “Dr. M.A. Simmons Liver Medicine,” which cured Indigestion, Biliousness, Colic, Costiveness, Dyspepsia, Sick Headache, Foul Breath, and Sour Stomach.

Health issues, of course, can effect us in so many ways, even in those intimate matters for which one would want the privacy of a doctor-patient relationship, if a doctor were ever around:

Let me start with my own gender: Men, can we speak in a discreet, but straight-from-the-shoulder manly way? Who among us hasn’t occasionally felt lacking in….enthusiasm? Yes, help is on the way: “Glandol” for “lack of vigor,” or if you prefer something a little more daring, “Dr. Dye’s Voltaic Belt.” And, let us be honest, we men can be weak. As we can be lured by a pretty face, the siren call of vice is constantly beckoning. Fear not, my friends; should there be unpleasant medical consequences, a Doctor Clarke of the Chicago Dispensary promises to “promptly, reliably, and thoroughly cure.” Chicago too far? Just purchase “Alternative Juice” from the Seroco Chemical Laboratory, or (and I’m not making this up) “Gono,” which apparently is unequaled in treating “all unnatural discharges.”

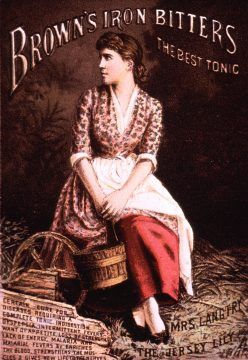

Women, draw near. I fully admit I don’t quite understand your issues, but there is someone who does. Lydia Pinkham. Mrs. Pinkham was born in 1819, but, thanks to her remarkable preparations of various herbs and spices (and, in their original form, a bracing dose of something more bracing), she is still with us today (in Walmart!), offering a variety of potions for the various stages of a woman’s life. She had a stern, but comforting face (which adorned every box of her medicines) and an intuitive grasp of marketing at a time before there were women doctors (“Only a woman can understand a woman’s ills.”).

Did any of these things actually work? After a fashion, as it depends what you were looking for. If you wanted a buzz, you were in luck. “Old Dr. J. Townsend’s Sarsaparilla” modestly sold as “The Most  Extraordinary Medicine in the World,” claimed to purify the blood and, in turn, cure a litany of other ailments. Along with the sarsaparilla part of the sarsaparilla, it was anywhere between 18 to 25 proof alcohol. Not bracing enough? “Brown’s Iron Bitters” promised relief from diseases of your liver, kidneys, and bowels, plus malaria, fevers, indigestion, and the ever-dreaded dyspepsia. For flavoring, they added 39 percent alcohol, and, according to the U.S. National Library of Medicine, a chaser of cocaine. Prefer the high in slightly lower doses? “Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup” (for teething babies!) managed to include both morphine and alcohol.

Extraordinary Medicine in the World,” claimed to purify the blood and, in turn, cure a litany of other ailments. Along with the sarsaparilla part of the sarsaparilla, it was anywhere between 18 to 25 proof alcohol. Not bracing enough? “Brown’s Iron Bitters” promised relief from diseases of your liver, kidneys, and bowels, plus malaria, fevers, indigestion, and the ever-dreaded dyspepsia. For flavoring, they added 39 percent alcohol, and, according to the U.S. National Library of Medicine, a chaser of cocaine. Prefer the high in slightly lower doses? “Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup” (for teething babies!) managed to include both morphine and alcohol.

How did all this glorious dosing come to an end? A confluence of factors led to intense pressure on Congress to break away from the contribution-influenced, laissez-faire approach and step in. Women were organizing and emerging as effective and persistent advocates for a number of social causes—Suffrage, of course, but also things like poverty, racism, and hearth-and-home issues like Temperance and public health. People and, in particular, children were dying, and in very large numbers, from disease-ridden food, incredibly toxic additives (Formaldehyde!) meant as preservatives or fillers, and adulterated medicines. In the Spring of 1905, the magazine Women’s Home Companion published Henry Irving Dodge’s “The Truth About Food Adulteration.” Finally, the slow-developing, but eventually spectacular success of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle (about the horrors of the meatpacking industry) brought public outrage to a boil. At the same time, an extraordinary series of articles by Samuel Hopkins Adams appeared in Collier’s. “The Great American Fraud” painstakingly, and sensationally, laid out the extent of the harm all those good-for-you medicines caused.

But, where to go? The manufacturers were still incredibly powerful, and their influence reached well beyond their friends in the House and Senate. Many general-interest newspapers relied on advertising revenues from them, and those contracts often came with non-disparagement clauses.

As much agitation as there was for change, the time never seemed ripe. The reformers needed something more than just the lurid reporting of horrible facts, and, starting in late 1905, they got it.

First, Teddy Roosevelt finally decided to weigh in, and, on November 5, 1905, he backed what came to be called the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, “[f]or preventing the manufacture, sale, or transportation of adulterated or misbranded or poisonous or deleterious foods, drugs, medicines, and liquors, and for regulating traffic therein, and for other purposes.”

First, Teddy Roosevelt finally decided to weigh in, and, on November 5, 1905, he backed what came to be called the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, “[f]or preventing the manufacture, sale, or transportation of adulterated or misbranded or poisonous or deleterious foods, drugs, medicines, and liquors, and for regulating traffic therein, and for other purposes.”

TR could be a potent force, but he wasn’t the final gatekeeper. The House and Senate needed to go along, and, there, the chances still seemed very slim. The Senate Majority Leader, Nelson Aldrich of Rhode Island, had absolutely no interest in it, publicly condemned it as an assault on individual liberties, and refused to bring it to the floor for a vote.

The bill’s prospects seemed doomed, until help arrived from an unexpected direction—the 135,000 member, normally apolitical, American Medical Association. The doctors weren’t as much interested in food as they were with drugs, but realized the two were intertwined. They made it clear to Aldrich that he was either going to relent, or all 135,000 of those doctors would rally in favor of the bill and tell their patients to do the same. Aldrich yielded, and the bill was passed by the Senate in late February 1906, and sent to the House. There, in a last gasp of the old guard, it was placed on ice for three months, while industry (with the help of the Speaker, Joe Cannon of Illinois, Stockyard Division) did what it could to stall, amend, and defang it.

But the tide had turned. TR was running out of patience, and commissioned another study, confirming Sinclair’s account of the filthy conditions of the meatpacking houses. Then the market itself shifted: the British refused to buy canned American meat, and Germany and France expanded that to any American meat at all. The ladies sent outraged letters, and the AMA urgent telegrams. The House passed it, and on June 30, 1906, Teddy Roosevelt signed it (taking a hefty portion of credit for himself).

This, of course, wasn’t the end. The new law was filled with compromises, and, with regard to drugs, in keeping with the times, it did not actually ban alcohol, narcotics, or stimulants. It did, however, require them to be listed on the label as “addictive,” and that, coupled with a provision that allowed mislabeled drugs to be seized and destroyed at the manufacturer’s expense, gave it some teeth. In 1911, the Supreme Court issued a ruling in United States v. Johnson that the prohibition against making misleading statements did not apply to claims of efficacy, which were merely free speech. As long as you disclosed the “addictive ingredients,” you were at liberty to claim your product cured whatever ailed the sufferer. In 1912, Congress amended the Act in response, but was only able to provide relief where it could be demonstrated that the manufacturer had knowingly made fraudulent claims.

Still, the Progressives had won something important. In a time in which every bit of regulation was considered a threat to the nation by the powerful, they had marshalled the key components of change in any democracy. They had held up a mirror to the problem, gained critical constituencies not present at the start, enlisted people of influence to take up their cause, and persisted. They had shown that government intervention on behalf of the people was, under certain circumstances, the morally correct thing to do.

That was Progressivism’s genius. It did not attempt to end inequality, or just redistribute wealth. Its bigger ambitions were grounded in basic right and wrong: end the corruption, the undue influence, the disenfranchisement, and the predatory behavior that led to injustice and appalling conditions.

It’s a lesson that is applicable today.